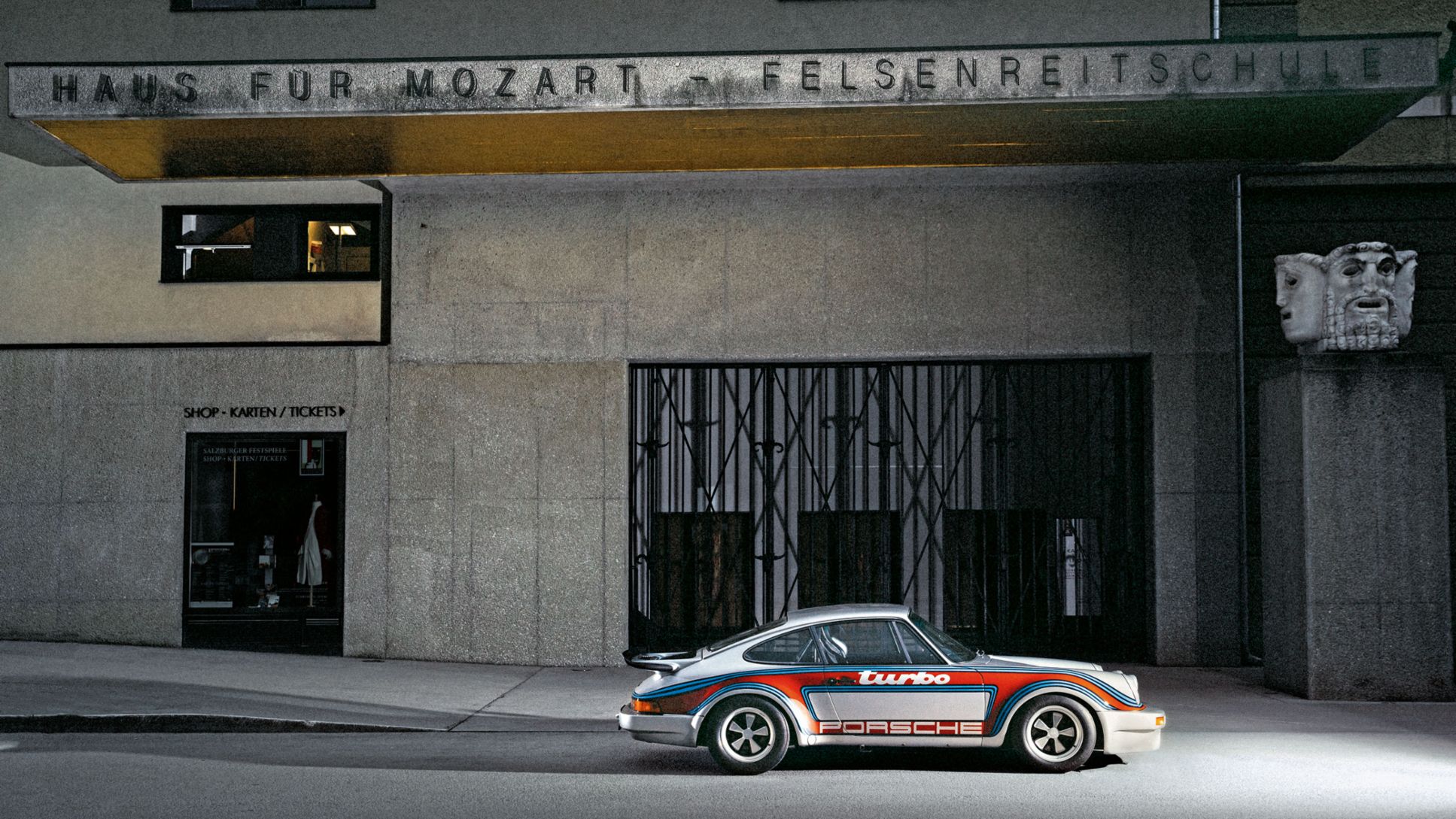

For the first time in forty years, the car takes the wide curve around Hotel Friesacher in the Austrian municipality of Anif. It comes to a stop right where Herbert von Karajan himself used to park whenever he was heading home from a rehearsal and wanted to treat himself to tête de veau en gelée in a cozy nook in his favorite restaurant. The car, a Porsche 911 Turbo (Type 930) delivered in 1975, is expected—by Wilfried Strehle, who was the principal violist under Karajan for eighteen years and who performed with the Berliner Philharmoniker on the world’s stages from Berlin to Tokyo. And in Salzburg, of course, where Karajan was born and launched the city’s renowned Easter music festival fifty years ago. Strehle now runs his fingers over the metal letters at the rear that spell “von Karajan”—as if there were any need to label this car. It’s one of a kind and unmistakable. “It’s a very emotional moment for me,” says Strehle, himself a major name in music. His elegant appearance—he’s sporting a red velvet Tyrolean jacket with a matching handkerchief and perfectly styled silver-gray hair—is a little reminiscent of his former boss.

Strehle never thought he would see the Turbo again. And certainly not here in Anif, a location with so much history for both himself and the car. With the last step on the gas, the noise of the engine emits a powerful crescendo that echoes off the hotel walls and then fades away. It attracts the attention of guests who have come to the state of Salzburg for the aforementioned festival. They stand around the Porsche. Some seem to recognize it. Will Karajan himself open the door and step out into a crowd of fans and a flurry of camera flashes? It seems like he just might.

There was always something a little otherworldly about Herbert von Karajan. Small in stature, he had an outsized presence. He often closed his piercing blue eyes when conducting, because he knew all the scores of his enormous repertoire by heart. He was a musician, artistic director, producer, conductor, building designer, and marketing visionary. A Renaissance man. A genius who was both admired and feared. He poured his relentless energy into every detail, no matter how small, which could lead to intense moments with his orchestra. Strehle recalls film sessions with the Berliner Philharmoniker in which the music was first recorded and then played back so the musicians could concentrate on moving their bows and instruments precisely in sync. It took many, many repetitions before the boss was satisfied.

Long list of special wishes

Karajan put the same meticulous attention to detail that made him a master of Nibelungen productions into the design of his cars. When he contacted the Porsche special order department in 1974 about a new Type 930, he made it absolutely clear that he wanted a lighter and more sports-oriented version of the standard production vehicle. Karajan dictated that the car should weigh less than one thousand kilograms and its power-to-weight ratio should be well under four kilos per hp—no easy task, given that the standard version was already at 1,140 kilos and 260 hp. The Porsche CEO at the time, Ernst Fuhrmann, carried out the special wishes of his prominent customer himself. Karajan’s Turbo was given the racing chassis of an RSR and the body of a Carrera RS, along with a racing suspension and rollover bars. The interior was rigorously stripped down. The backseat was replaced by a steel roll cage, while the radio and any symphonies it might have played gave way to the harmonies of the flat-six engine, which could mobilize around 100 more hp thanks to a larger turbocharger and a sharper camshaft. Lightweight construction even extended to replacing the door handles with slim leather straps that opened the catch when pulled. And Porsche specifically requested permission from Rossi, the vermouth producer, to replicate the Martini Racing paint job from the 911 Carrera RSR Turbo 2.1 that finished second in the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1974.

Karajan, a mastermind throughout his life, made so many records with the Berliner Philharmoniker that he was already dreaming in the 1970s, rather immodestly, about the immortality of his life’s work. “For him there was only one direction: forward,” recalls Strehle. “He never rested. He kept on learning his entire life, and kept developing both us and himself, including the business aspects.” The maestro’s constant desire to move forward expressed itself not only on the stage but also in his hobbies. And his favorite means of forward locomotion was the brand from Zuffenhausen. Over the years, he drove a Porsche 356 Speedster, a 550 A Spyder, two 959s, and several Porsche 911s. “Year after year we would stand in front of the latest model like little boys, absolutely fascinated. Karajan was a model for us in everything he did, and of course we tried to emulate him.” A native of the Swabian region of Germany, Strehle shares Karajan’s love for Porsche. One year after joining the Berliner Philharmoniker, he purchased his first 911. The Turbo remained just a dream. Until today.

Strehle climbs into the slim, leather bucket seat, which was perfect for Karajan’s 173-centimeter frame. He carefully turns the key in the ignition and listens in rapt attention. The Turbo in the rear starts by clearing its throat and then lets loose a powerful baritone vibrato that pierces marrow and bone right through to the heart. Strehle reverently steers the Porsche through the town and heads off toward the majestic mountainous landscape of southern Bavaria. He pulls the sports car to a stop at a meadow covered with flowers. On this country lane, which today is called Herbert-von-Karajan-Straße, the well-known photo was shot in the 1970s that would later grace the cover of the Berühmte Ouvertüren (Famous Overtures). Strehle points to a solitary house with a white chimney: Karajan’s estate. The Turbo is quiet, and a nearly reverent air of stillness reigns. The view of the Porsche in front of what used to be its home, nearly thirty years after the death of its famous owner, calls for reflection.

As if seeking to console the sports car, Strehle now heads to a place where it used to run free—the winding roads of the Alps. The panoramic road leading up to the Roßfeld was Karajan’s favorite stretch. The ever-so-disciplined conductor used to get up at six in the morning to study scores and do yoga—and sometimes to drive up into the mountains to greet the first rays of light. It’s now time to give the Karajan Porsche free rein on the nearly sixteen kilometers of the panoramic circuit. As Strehle shifts down and lets the rpm levels rise, an inferno erupts from the rear, like Wotan emerging from the clouds. It’s enough to make you want to swing a Valkyrie’s staff out the window and storm the peak on 360 horses accompanied by loud battle cries. Karajan, by contrast, apparently did not push the Turbo to very many heights. When he sold it in 1980, the odometer showed just three thousand kilometers. But the few years in the possession of the conductor were enough to give the legendary Porsche its current estimated value of over three million euros. The car’s sixth owner, who bought it in 2004, has added it to his secret collection in Switzerland and has not driven it a single time—yet.

Unforgettable dynamo

What remains of Herbert von Karajan, the man who shaped the perception of sound for an entire generation of musicians and music lovers? Sometimes Strehle listens to old recordings, such as that of Puccini’s La Bohème from 1972. “You still hear this incredible passion, this thrust, this force, which might also explain—in metaphorical terms—his fascination for Porsche.” A committed Buddhist, Karajan did not believe death marked the end. Perhaps it really is true that parts of our soul live on in the objects and people that have accompanied us through life. And perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Turbo found its way to Anif again after almost forty years. Still insistent, still wanting to move forward. Still with an otherworldly presence.

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 382

Text by Lena Siep // Photos by Patrick Gosling, Siegfried Lauterwasser/Karajan-Archiv