A broken leg marked the start of her life. Or did a broken leg mark the start of the end of her life? No one knows how she herself would have set about telling her story. Annie Bousquet departed this world more than half a century ago.

One thing is certain: racing history would have been deprived of a legend if Bousquet had not crossed her skis while zooming down a slope in Sestriere in 1952. Which is why, on the afternoon that changed her life, she was sitting in a hotel lobby where she happened to overhear two Italians talking about motorsports. One of them was Alberto Ascari, who would win the Formula One title that year and the next, only to suffer a fatal accident in Monza in 1955. Vienna-born Bousquet, née Schaffer, who was married to a Frenchman and had a ten-year-old daughter, was spellbound by Ascari’s stories of the world beyond two hundred kilometers per hour—what a contrast to her sheltered existence, to days filled with tennis, skiing, and horseback riding. She promptly resolved to rev up her life.

From a record drive to the hospital

Her leg had hardly healed from her skiing accident before Bousquet entered her first race, driving a Renault 4CV in the Alpine Rally in France. When the transmission broke down she had to pull out. But neither mechanical failures nor condescending remarks from the predominately male competitors could dampen her enthusiasm. Her driving style, a perilous combination of courage and cockiness, made her an early star of the sport. But crossing the finish line, as she did in the 1953 Mille Miglia, tended to be the exception rather than the rule. She was constantly flirting with the limits of physics, fueling an ever-greater hunger for success, and heading unswervingly for the day on which she would take her place in the annals of racing history.

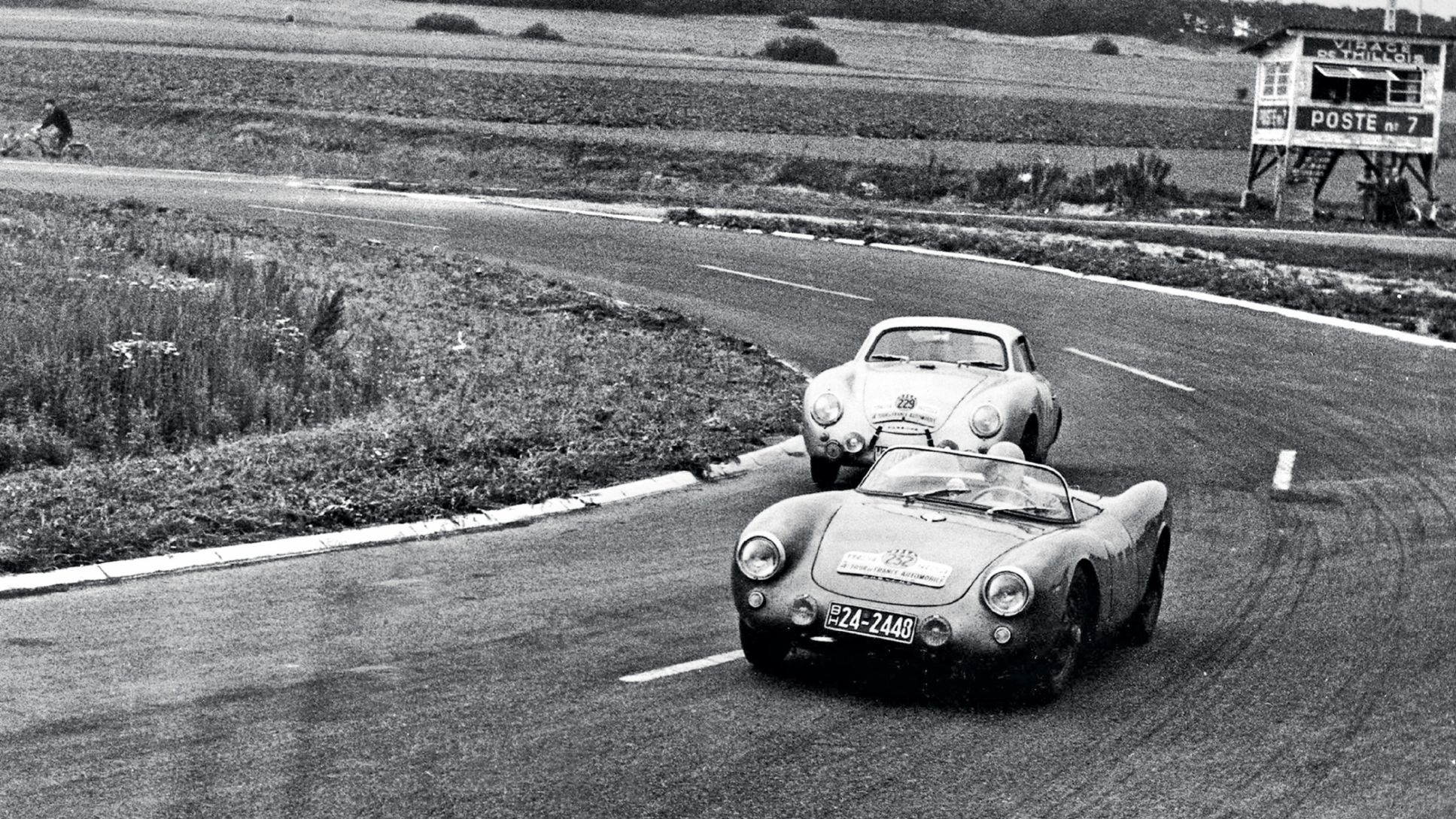

On August 16, 1955, the women’s world speed record was waiting to be broken south of Paris at the Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry. As usual, Bousquet appeared impervious to all risk—even at the place where her idol Ascari had lost his father in a racing accident in 1925. Her only thought was to break the 1934 lap record of 215 kmh, set by English racer Gwenda Hawkes, with whom she constantly found herself neck and neck. Bousquet entered the best race car available: a Porsche 550 Spyder made specially for her by the Wendler chassis-building company in Reutlingen. A Spyder in Racing Blue, it ran on motorsport fuel, rolled on special tires, and the cockpit was clad on the sides. Everything about the car had been optimized for this competition. And just three and a half years after her first race, Bousquet reached the pinnacle of her career. Putting in an incredibly concentrated performance, she posted a speed of 230.5 kmh on her fastest lap. And secured her longed-for world record!

But as had occasionally happened before, Bousquet ended her day in the hospital. Euphoric about the lap time, she had immediately resolved to set a new hour record as well. But a tire blew out at over 200 kmh, and her car smashed into a wall. Relief was palpable in Zuffenhausen when her telegram arrived: “Broken leg, not neck, in good spirits. Yours, Annie.”

Racing after driving through the night

In the wake of this record drive, luck turned its back on Bousquet. In January of 1956, her husband Pierre died in a car crash. In June of that same year, she entered the twelve-hour race in Reims—and lost her own life. A tragedy in the making: even after the death of her husband, Bousquet continued to race, organizing everything on her own, including the lead-up to Reims. Her 550 Spyder was being repaired by Porsche and wouldn’t be ready until the day before the race. Bousquet picked it up and drove five hundred kilometers through the night to the circuit. Once there, she insisted on driving the first stint. In the seventeenth lap her left front wheel left the track, the car flipped over, and this time Bousquet broke her neck. The contest went on for eleven more hours as the other drivers raced past the site of the accident—some of them surely reflecting on this extraordinary woman who, in her early thirties, would no longer be striving for even higher speeds. In response to Bousquet’s risky driving style and death, the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, which put on the 24 Hours of Le Mans, stopped allowing women to compete—a ban that wouldn’t be lifted until 1971.

As for Annie Bousquet’s own take on her fast-paced and far too brief racing career, she might have begun her story with this version of the sentence: a broken leg marked the start of my life.

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 387