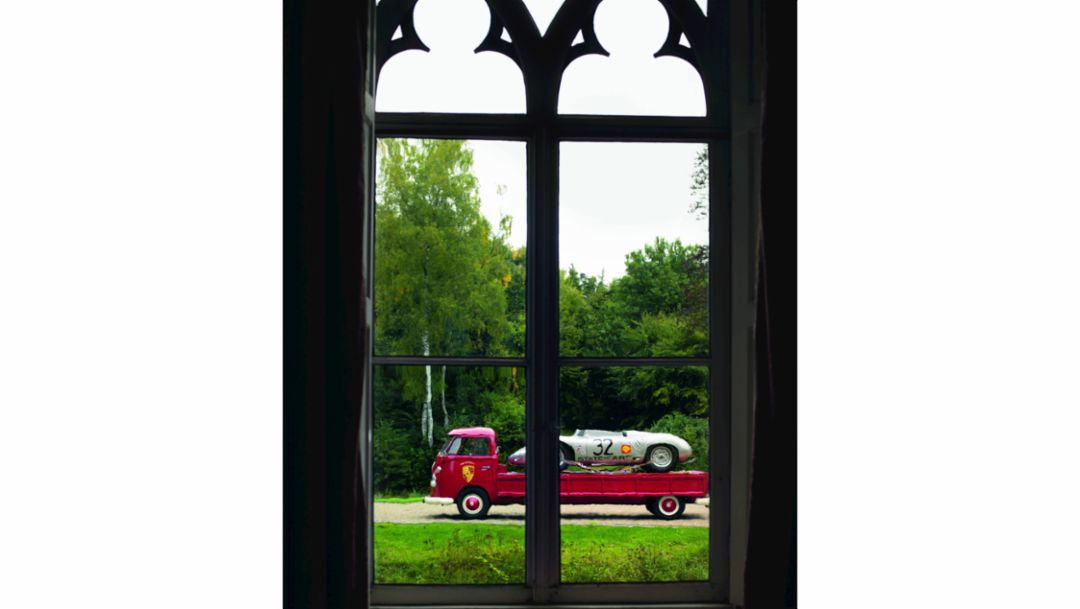

Sunlight breaks through the clouds above the grounds of the estate, and threads its way along the branches of the venerable trees, through the sweeping boughs of a magnificent red beech. The canopy of leaves diffuses the light and magically transposes us from the present to the past. The Porsche 718 RSK on the gravel driveway takes on a soft golden glow. And suddenly it’s there – that special quality, or power of enchantment, that a historic race car commands. No one is indifferent to this power. The lady of the estate, Cornelie Petter-Godin de Beaufort, walks slowly around the car once, and then again. It seems to ignite something in her, propelling her thoughts back to another, faraway time.

Cornelie Petter-Godin de Beaufort is 84 years old. Her movements are cautious, her eyes are lively and sparkle. As she circles the car, her hands are thrust deep into the pockets of her jacket, as if to stop herself from caressing it. “Cars were just a means to an end for me,” she says. “They were a promise of freedom. But for my brother, they were much, much more.” We are in the Netherlands visiting Maarsbergen Castle, the ancestral seat of the aristocratic Godin de Beaufort family. Carel Godin de Beaufort, Cornelie’s brother, was a legendary race-car driver who loved speed, risk, and above all his Porsche. He might not have been the most famous race-car driver of his time, but he was certainly one of the most honest. He had courage, style, and class, and is honored to this day as one of the last great warhorses and true amateurs in motorsports.

A time travel

The 1957 Porsche 718 RSK Spyder that stands before us in the autumn sunlight is a car that he drove in road races and hill climbs. It is a successor to the legendary 550 Spyder, and the two-seater version of the Formula Two single-seater in which he lost his life at the young age of thirty while training on the Nürburgring in 1964. This visit to the estate is therefore also a journey to the past. Back to the golden years of racing, when you wouldn’t find any pros with million-dollar contracts on the roads and tracks but instead fervent amateurs given to spending their last penny on their hobby, who unfortunately often paid with their lives as well. You can sense this spirit when you look at the race car – and when you walk through the castle.

Cornelie Petter-Godin de Beaufort keeps his spirit alive. She was not only Carel’s sister, but also his team manager, official timekeeper, navigator, cook, best friend, closest confidante, and kindred spirit. As she gazes at the Porsche, her head tilted slightly to the side, her eyes take on a faraway look. Who knows what images are running through her mind right now? The long nights of the 24-hour races in Le Mans, where she assisted her brother in the pit? The drives to the Mille Miglia? The glittering parties after the Formula One races in Zandvoort, when the racing elite of the late 1950s and 1960s gathered at Maarsbergen Castle? For a few moments she indulges her nostalgia, and perhaps also her sorrow. Then she returns to the here and now, and a smile plays on her lips. Her fine sense of humor returns as well.

“Carel actually drove in his socks”

“By the way, the car didn’t look quite as good back then. I never saw it so clean or well cared for. But that’s the type of thing I’m not supposed to reveal, wouldn’t you say?” As the young lord of Maarsbergen, Carel Godin de Beaufort was destined to spend his life looking after his lands, doing a little farming, trading a few stocks and shares, and whiling away evenings at gentlemen’s clubs. But that was all too staid, too slow, and too monotonous for him. Carel’s capacity for devotion and his desire for speed made him a race-car driver. And it is no coincidence that he loved his Porsche above all else. The car standing in front of Cornelie contains nothing superfluous. And precisely for that reason, it could serve as a blueprint for all Porsche models. It is the quintessence of speed, purity, and simplicity.

Its aluminum shell covers a tubular space frame made of seamless steel. Its interior, too, seems stripped down to the essentials: two seats, three pedals, a simple hand brake, and the gearshift. Very pure. And very small. “Carel actually drove in his socks,” says Cornelie. “He was quite tall, and those few centimeters made a difference. And of course it was also unpleasantly hot.” She tears her gaze away from the car and invites us to come inside. There, too, the past is omnipresent. A portrait of her brother stands between two illustrated volumes about the Zandvoort Grand Prix and the Porsche 718. In the background, suits of armor shimmer in the fading light. The de Beauforts are a large family with an illustrious history. Every sailor knows their name. The Beaufort scale for classifying wind speeds commemorates Sir Francis Beaufort, a nineteenth-century member of the Irish branch of the Beaufort family.

“He said horses made him seasick”

Cornelie wipes the dust from a thick black photo album before opening it. One page shows her father, a successful equestrian show jumper. Another shows Carel as a young boy. Cornelie recounts some of his pranks. How he secretly tied an important visitor’s automobile to a tree with the aid of rubber belts, which slowed the car and then slammed it back against the trunk. There are stories about how he took sports cars apart down to the last screw, and then put them back together again – only to smash them up for good on test runs. “He was smitten with cars from a very early age. Not with horses, like his father.” Cornelie closes the album. “He said horses made him seasick.” Their father died in 1950. After his death there was no one to keep the son’s enthusiasm for automobiles in check.

Carel started entering rallies, and his talent attracted the attention of Porsche racing director Huschke von Hanstein. Carel entered the 24 Hours of Le Mans for the first time in 1956. He followed up with races on the Nürburgring, as well s in Venezuela. He drove to victory in Innsbruck and Spa, and joined von Hanstein as a factory driver to win the 12 Hours of Sebring. But he entered most of his races with his private team, which was called Ecurie Maarsbergen. The team consisted in large part of Carel, Cornelie, and their mother. And the fourth member of the Ecurie Maarsbergen team – the mechanic Ari Ansseems – joined them more by chance. “We were in Le Mans. Carel had a young man who was supposed to be a mechanic and a young woman with him. But one day they just disappeared. The 24 Hours of Le Mans is an awful lot of work, I can tell you. Carel started to shout and swear. Someone heard him up in the stands, and shouted back, “Can I help you?” He was a mechanic who was actually there as a spectator. He helped us that night. And then for years to come.”

A mechanical masterpiece: vertical-shaft four-cylinder boxer engine

To this day, the 718 is a mechanic’s dream. Its inner life might be even more exciting than its exterior. Cornelie doesn’t open up the car herself. That is Roy Hunter’s job. He looks after the car for the Heritage Racing collection owned by Albert Westerman. Roy himself looks a little like he has stepped out of another era. Elegantly dressed in dark blue, his hair combed back in a 1950s style, he opens the hood with a simple oversized screwdriver to reveal the vertical-shaft four-cylinder boxer engine, to this day considered a mechanical masterpiece.

The fourfold air-inlet flaps on the rear fenders, which Roy also opens with a practiced half-turn of the screwdriver, help to cool the drum brakes. The sports car’s obligatory spare tire is stored in a hidden compartment under the front hood, which is a rare masterpiece in itself. The fact that its surface has properties different than the silver paint on the rest of the car is a technical necessity, like everything else on the RSK. Although it becomes very hot, the front hood serves a cooling purpose.

The engine howls

Time for a test-drive. The engine starts by emitting a staccato of single firings in its lower rpm range. But with the first double clutch, the sound swells into a dry, aggressive roar. It is surprisingly awkward to turn the car around. Due to its unusual gear configuration, reverse is locked because otherwise it would be too easy to shift directly into it from first gear. Upon completing this maneuver, the car moves slowly down the gravel driveway. A quick burst of gas and we shift into second gear, and then into third as the 148 horsepower start to kick in. Fourth gear. The car could reach 260 kilometers an hour, although we don’t reach that today. But still: 3,000, 4,000, 6,000, 7,000 rpm. The engine howls. You feel every piece of gravel, are confined to the narrow cockpit, and at some point no longer know where your body stops and the car starts.

“I was thrilled by the sporting side of it,” Cornelie recalls. By that she means much more than the urge to enter competitions. It had to do with the real sportsmanlike approach to facing big challenges or risks, or perhaps just one’s own limitations, with courage and a pioneering spirit—and with dignity and a friendly attitude toward one’s rivals. “Carel was a real extrovert,” she says. “Generous. Everything about him was big. He invited everyone to join in. True, he could also be difficult, very difficult indeed if he wasn’t happy with something or if something wasn’t working. He was extreme in that respect as well.” His rivals knew how to deal with him, and over the years they became close friends. Wolfgang Graf Berghe von Trips, the German aristocrat in a race car. Gerhard Mitter. Jim Clark. “I think friendships meant a lot more back then. The drivers, all of us, we were like a sworn alliance.” She falls silent for the first time. “They were very special people,” she says.

A final look

Von Trips, Mitter, Clark – three drivers who, like her brother, paid for their passion with their lives. Cornelie Petter-Godin de Beaufort lost not only her father and her brother at an early age, but also her husband, a talented equestrian show jumper and elite soldier whom she met shortly after Carel’s death. He died just a few weeks after they were married, before the birth of their daughter. His death, too, seems larger than life. During a military exercise, he threw himself onto a young recruit who had fired his grenade at too steep an angle, saving the young man’s life at the cost of his own.

As our visit draws to an end, Cornelie accompanies us back outside, and once again she walks around the 718. She takes a final look. The side flaps are now closed, as is the hood. You almost have the impression that the car is waiting for something, as if its grand appearance is yet to come. Cornelie nods, almost in surprise, as if she had forgotten after all these years. “Yes,” she says, “it is a very beautiful car.”

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 375

By Jan Brülle // Photos by Albrecht Fuchs, Julius Weitmann

Copyright: The image and sound published here is copyright by Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG, Germany or other individuals. It is not to be reproduced wholly or in part without prior written permission of Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG. Please contact newsroom@porsche.com for further information.