Edgar Barth won the 1957 Schauinsland hill-climb race in a Porsche 718 RSK. His son, Jürgen Barth, follows in the tracks of his father in the new 718 Boxster S. “Training was mainly done at night,” says Jürgen Barth. “It was relatively safe to follow the ideal line, because the headlights of oncoming cars made it possible to see them in good time.”

Just 9 years old at the time, the now 68-year-old Barth still remembers it well. He was allowed to come along and sit in the passenger seat as his father Edgar roared up the 173 corners of the 12-kilometer mountain road southeast of Freiburg with breathtaking speed. “Those were naturally magic moments for a young boy,” recalls Jürgen, who grew up in the motor-racing world and later became one of the best in the sport himself.

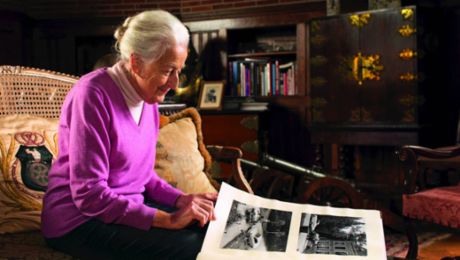

An album full of memories

Jürgen Barth is sitting at a table in the hotel Die Halde on the summit plateau of the Schauinsland mountain; before him lies a gigantic, fawn-brown leather tome. The album weighs nearly 10 kilograms and just barely fits in the luggage compartment of the 718 Boxster S in which Barth meandered his way up the old hill-climb route. There has been an inn at this location since the fourteenth century, and Porsche drivers have stayed here time and again over the past sixty years.

In the 1950s and 1960s, test engineers and race-car drivers from Zuffenhausen were regulars at the Halde. “I came here often with my father,” says Jürgen Barth. “The drivers trained for the race on the route up the Schauinsland, and on the steep descent down to Todtnau they tested the brakes.” Ideal terrain for putting a car through its paces. The German name for the slope on which the road and a few ski runs descend into the Wiese river valley is as evocative as it is apt: Notschrei, or “cry of distress.”

Jürgen opens the heavy cover of the album as one would the top of a treasure chest. The picture book is full of memories and stories that capture and reflect his father Edgar’s entire racing career. Edgar Barth started racing motorcycles in 1934 and was among the pioneers of motor racing in East Germany after World War II. He raced for Porsche on the Nürburgring for the first time in 1957, for which he received a lifetime ban by East German authorities. He continued his career with Porsche in West Germany. He was a slim, handsome man with slicked-back hair–in the photos, nearly always covered by a racing helmet.

Some of the black-and-white photos include a little boy. In one of them, he sports an adorable peaked cap. “That’s me,” says Jürgen Barth. He flips through the pages, pausing thoughtfully and smiling from time to time as he points to the most important stations in his father’s career, such as his victory in the Autobahnspinne Dresden in 1953, the Targa Florio in 1959, and his four victories at the Schauinsland race. Edgar also won the European Hill Climb Championship in 1959, 1963, and 1964. His car of choice back in the day was a Porsche 718. He initially drove variants with four-cylinder boxer engines, but later switched to eight-cylinder engines.

The new Porsche 718 Boxster S echoed throughout the mountain forest

“Some of the engine sounds in the new 718 Boxster S remind me of the old race cars,” says Jürgen Barth today. “The dark, muffled growl while accelerating, for example.” A few hours ago, when he took to the Schauinsland course in the 718 Boxster, the sound echoed throughout the mountain forest. Jürgen describes the way the new four-cylinder boxer engine unpacks its power as “fantastic,” the suspension as “balanced,” and the brakes as “outstanding.”

“You know there’s a turbo behind your back propelling you, but it feels like a naturally aspirated engine.” The classic among hill-climb races, the way up to the panoramic summit at 1,284 meters is the ideal road on which to familiarize oneself with the Boxster’s capabilities. “The 718 Boxster S is wonderfully compact and light. It reminds me of the earlier 911s.”

Jürgen Barth knows the Porsche 911 like the back of his hand. In 1969, he entered the Schauinsland race for the first time in a 911 T. The car was an old rally car that Jürgen purchased with 2,000 German marks from the start-up money he had received. The organizers wanted to have him and Hans-Joachim Stuck on board at any cost, as the youngsters were billed as the sons of the former kings of the mountain. Stuck entered the race in a BMW Alpina 2002 ti, but was done in by a patch of oil. Barth, meanwhile, demonstrated his driving talent and promptly took sixth in his class in his debut performance. “I liked hill climbs a lot,” he says. “You had to know every corner in detail, because there was no codriver like in a rally. And you had only one chance, unlike in circuit races, in which consistency and strategy are much more important.”

“Maybe driving fast was in my blood. How I really learned it, though, was through the many opportunities that I had as a driver of the service vehicle, such as in the Safari Rally in Kenya for Björn Waldegård,” recalls Barth. Because he also had a detailed understanding of the car’s technology, he was able to drive fast, yet gently, which few others could do–an ability that made him one of the finest endurance drivers of his era. Today, Barth says that “the art of racing is not to drive 100 percent at one point in the race and post the fastest lap, but to go as close to 90 percent as you can for the whole race. If you can manage that, then you’re really fast.”

Barth has always been a mechanic

Before becoming a race-car driver, Jürgen Barth trained for a practical career. His father, who died in 1965, insisted on it, and his son took his advice. First, he apprenticed as a car mechanic with Porsche, then he completed his training with a second apprenticeship as an industrial clerk. This dual focus shaped his entire professional life: he has always been a mechanic, a public relations ace, and an exceptional organizer, which he has demonstrated time and again in the Porsche racing department. To this day, Barth is still racing.

On June 12, 1977, Jürgen Barth steered a smoking Porsche 936 across the finish line at Le Mans, capping a triumphant performance. Alongside Jacky Ickx and Hurley Haywood, he took the overall victory in the 24-hour race. During the last two laps the Porsche’s engine was running on just five of its six cylinders. The driver with the ultimate soft touch, Barth was left to do the honors of driving home the team’s massive lead while staying within the rules. A few days after his biggest motor-racing success, he once again found himself on a plane, toolbox in tow, en route to Australia. His task this time: to provide technical support to Polish race-car driver Sobiesław Zasada, who was in a most promising position with his Porsche 911 in the London–Sydney Marathon, though he eventually finished thirteenth.

When you sit with Jürgen Barth and talk about old times and the new 718 Boxster S, your gaze naturally drifts to the golden ring on the ring finger of his right hand. The shape is somehow familiar. “That’s a Nürburgring ring,” explains Barth. The striking piece of jewelry depicts the Nordschleife, the racetrack on which Barth won the 1,000-kilometer race with Rolf Stommelen in a Porsche 908 in 1980. All winners of major races on the track in Germany’s Eifel region received a “Nürburgring.” This tradition began with Rudolf Caracciola in 1927 and ended with Barth and Stommelen in 1980. Yes, says the man with the golden ring, it does feel like he brought something full circle. As if his motor-racing career and his father’s somehow complemented each other and together formed a whole. “He never won at Le Mans or on the Nürburgring, and I never won the Targa Florio or Schauinsland.”

Jürgen Barth is back in the 718 Boxster S. The top is down, the Lava Orange roadster is barreling through the Holzschlägermatte corner on its way down to the valley. Back in the day, on this sweeping corner of the Schauinsland hill-climb race, over 10,000 spectators lined the course on wooden stands and the hillside to cheer on the racers. Today the northward view extends far into the distance, taking in the Rhine Valley and even stretching into Alsace.

Barth is currently collecting material for a racing cookbook

“The 718 Boxster S, after all, is not just a car for the attack, but also for a leisurely stroll, as it were,” says Barth. And now, after revisiting days past on the Schauinsland and many other courses, that is precisely the plan: a relaxing ramble down friendly lanes beyond the Rhine, where France beckons with an alluring way of life that appeals to Jürgen Barth. He is currently collecting material for a racing cookbook, and it would be a shame to pass up a little research tour of Alsace along the way. Barth hits the gas and the 718 Boxster S zips off with its sonorous growl.

The Schauinsland Hill-Climb Race

In the Middle Ages, people mined for silver and lead on the Schauinsland. Later, lumberjacks plied their trade on the mountain’s slopes. To facilitate the transport of wood down into the valley, the city of Freiburg built a road on its local mountain. It was finished in 1896. Some two decades later, the old logging road caught the eye of some of Freiburg’s motor-racing enthusiasts. The result: on August 16, 1925, the first race–dubbed the “ADAC Berg-Rekord”–was held on the Schauinsland. In total, 126 motorcycles and 72 cars took part.

The winner covered the approximately 12-kilometer course, with its 173 corners and maximum grade of 12 percent, with an average speed of 62.3 km/h. The race immediately became a public sensation. In its heyday, more than 10,000 spectators thronged the roadside to catch a glimpse of the world racing elite, private drivers, and local favorites testing their skills. The ranks of the winners of the 38 Schauinsland races include the likes of Rudolf Caracciola, Hans Stuck, Bernd Rosemeyer, Hans Herrmann, Edgar Barth, Gerhard Mitter, Rolf Stommelen, and Mario Ketterer.

On July 8, 1979, Ketterer posted an average speed of 134.76 km/h, setting a record that still stands today. The last Schauinsland race was held in 1984 on a shortened course. Strict environmental and safety regulations ultimately sealed the fate of the event. Today, races are held at irregular intervals on the Schauinsland with classic race cars and high-powered celebrity participation.

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 378

Text by Sven Freese // Photos: Steffen Jahn

Consumption data

718 Boxster S: Fuel consumption combined 8.1 l/100 km, CO2-emissions 184 g/km

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Course-section-of-the-Schauinsland-hill-climb-racetrack-(2).jpg)

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Porsche-718-Boxster-S-(4).jpg)