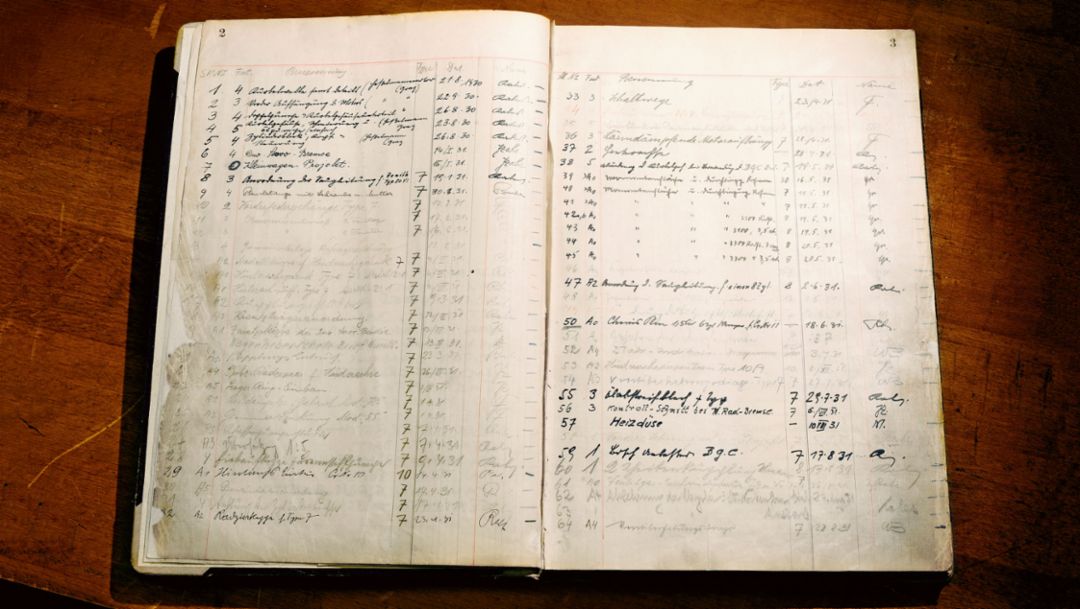

It sits unremarkably in a gray safe in a climate-controlled room: the first ledger of the Porsche design office, stored in a fireproof room in the archive of the Porsche Museum. In the timeworn ledger one can find order number 1, placed on August 21, 1930. The job involved manufacturing individual components for a “Hesselmann engine,” a cross between a diesel and a gas engine—a sign of the company’s innovative spirit since its inception. Order number 7 was of another dimension altogether. “Small-car project,” reads the description in the ledger. The Wanderer company planned to motorize the masses and needed a concept with which it could economically and inexpensively develop what was then considered a luxury item into a Volks-Wagen—a car for the people. A clever idea, as history would demonstrate. The order book provides an illuminating look at how Ferdinand Porsche and his small team of just nineteen employees embodied the vision of design creativity.

On April 25, 1931, Professor Porsche had his company officially entered in the commercial register. From that day forward, “Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche GmbH, Konstruktionen und Beratung für Motoren und Fahrzeuge,” based in Stuttgart, was officially on the books. The first five projects were started in 1930 in St. Ulrich, Austria. The drawing board was in the bedroom of Porsche’s son Ferry. But the office moved to Stuttgart at the beginning of 1931, initially renting space in the city center. The idea of a neutral design office was still unheard of in the automotive world. Ferdinand Porsche did not, at the time, harbor the intention of building his own cars. His aim was to carry out technical projects for a variety of clients as well as charge licensing fees and patent royalties. The first order book illustrates in impressive fashion how the Porsche office became a hotbed of innovation for the German automotive industry.

Porsche’s vision had begun to take shape

In 1932, Porsche received the commission to develop a small car for the Zündapp motorcycle manufacturer. The car was intended to deliver a shot in the arm to the struggling manufacturer of two-wheelers. With the revival of fortunes in the motorcycle market, however, the project was put on ice. The work on the Type 12 had not been in vain, however. For the first time, the idea for the later Volkswagen (the Type 60) manifested itself. Porsche’s vision had begun to take shape, and on April 27, 1934, Erwin Komenda completed the first drawing for the Type 60, as the “Volkswagen Project” entry shows.

In early 1933, the Porsche design office received a commission from Auto Union to develop a sixteen-cylinder race car according to the rules of the 1,650-pound racing formula. In December of 1932, months before concluding the contract, the Porsche team began work on the Type 22 mid-engine P race car. The legendary Auto Union Grand Prix car set new standards.

Ferry Porsche turned the design office into the Porsche automobile company

For company historians, the first “sketchbook” and the following four notebooks are the most important sources shedding light on the early history of the company. They document the years 1930 to 1945. The ledgers contain some 300 projects. The “Porsche” signature first appears on January 30, 1931. A youthful hand recorded “Connecting rod with screw and bolt”—entry number 9, penned by apprentice Ferry Porsche, who would later turn the design office into the Porsche automobile company.

Whereas the initial five projects were completed in Austria, the first Stuttgart-based job was order number 6: a “duo-servo drum brake.” This, too, was a comparatively small job, especially when compared to order number 7, a small-car project that would later make automotive history as the Wanderer W21/22. In Ferdinand Porsche’s original file drawer, the address can still be found under “W.”

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 379

Text by Dieter Landenberger // Photos by Markus Bolsinger

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Entries-in-the-first-ledger-of-the-Porsche-design-office-(2).jpg)

-2.jpg/jcr:content/Porsche%20911%20S%202,0%20Targa%20(1967)%202.jpg)

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Rear-of-the-Porsche-356-A-1600-(1956).jpg)

.jpg/jcr:content/b2-Porsche-919-Hybrid-(right).jpg)