The Californian now maintains a collection of rare classic cars. And he travels the world to find vintage models for prominent private collectors.

An inconspicuous garage on a normal residential street near Los Angeles. Blue Nelson opens the hood of a Porsche 356 1500 Coupé built in 1953. Very carefully. He doesn’t want to blow up any dust. The reason is immediately clear. Two soft objects lie on the tank. They are nests made out of the stuffing in the car’s seats. Between them, on the tank cover, lies the desiccated body of a dead rat. Nelson pulls a second rat—this one very much alive—from the nest on the left and holds it up by the tail to the light. More rodents are hiding in the car’s interior and under the spare tire. “I spray the car every six hours with bleach and neutralizer, inside and out, to detoxify the excrement and eliminate the odor,” he says, reaching for a spray can.

A piece of automotive history

Despite the stench, Nelson beams. For him, classic cars like this weathered Porsche, which was probably once yellow, are the gold standard. A piece of automotive history—with a Belcanto radio from the 1950s, spare parts, yellowed papers, and other artifacts on the backseat. He liberated it from a garage in San Diego a few days ago, wearing a protective suit and filter mask. The car had been there, surrounded by household items, for 51 years. The original engine and the four-pipe Abarth exhaust system lay hidden in a corner beneath boxes.

Henry DeWitt passed away decades ago, and his widow Joan had recently advertised his 356 for $30,000 on the advice of a specialist. “Experts,” mutters Nelson with scorn. He called Joan immediately and informed her of the real worth of the vehicle that had sat untouched for years. An initial appraisal in San Diego confirmed his estimate. The car is a rare model worth many times the suggested price. Nelson’s honesty comes at a cost.

“To pay for this find, I had to sell some other cars, including my 1949 Chrysler New Yorker,” he says. He looks a little sadly at the space once occupied by the blue Chrysler, which he used for driving his parents around and chauffeuring couples to weddings. But it was worth it to fulfill a lifelong dream. Nelson, a director’s assistant who has worked on movies and TV series like Baywatch and CSI: Miami, calls the car the “find of my life.” And he wants to do the right thing. Joan DeWitt is in a wheelchair. She should get a fair deal, “so she can pay her medical bills and enjoy the rest of her life a little more.”

A collection unlike any other in the United States

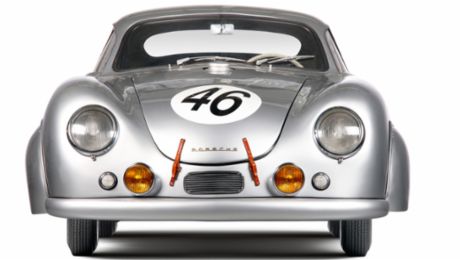

The Porsche is now in the San Fernando Valley, in Nelson’s garage—which is nearly 5,400 square feet in size and was originally built in the 1920s to press olives. Nelson has renovated the garage with care, and it now houses rare classic cars— a collection unlike any other in the United States. A red 1957 356 A 1500 GS Carrera Speedster with original Rudge center lock rims. A 1957 aluminum Porsche Beutler, built by hand, with a 1.5-liter engine. Porsche made just five of them, he says. Four still exist.

Then there’s a canary yellow and blue convertible version of the Rometsch Beeskow, also from 1957. Its aluminum body was made by hand in Berlin by Friedrich Rometsch. And finally, the car that ignited Nelson’s passion for Porsche: a 1962 roadster, with two air-inlet grilles on the engine hood. It was in this jewel that Gary Nelson drove his wife and their newborn son home from the hospital 47 years ago. “A love for Porsche was instilled in me at birth,” says Nelson.

As a child, he washed his father’s Porsche for 50 cents. He used the pocket money to buy Christophorus magazines from the 1950s and immersed himself in pictures of faraway countries and works of art on wheels. “The magazine triggered a deep desire in me to travel and find early 356s.” He made an enormous collage of photos from Christophorus calendars and hung it in his room. It now adorns the garage, along with old Grand Prix posters, photos of his parents in their cars, and a glass case full of his father’s racing trophies. Two rotating jewelry cases are piled high with automotive accessories from the 1950s: rare key chains from Porsche, patches, knickknacks for the dashboard, Porsche pins that men once wore on the collars of their suit jackets, and advertising materials from dealerships.

Nelson’s father Gary is a well-known television and film director (Gunsmoke, Gilligan’s Island, The Black Hole). He entered Porsche races in the 1950s, especially on racetracks in Santa Barbara and Palm Springs and at Paramount Ranch. Nelson’s mother, who died two years ago, was the actress Judi Meredith (The Raiders, The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show). She too loved elegant automobiles and would pick up her son from school in a 1973 Ferrari Dino 246 GTS. “I would stand in front of the school building and hear her shifting through the gears from afar on Mulholland Drive,” recalls Nelson, who describes his parents as a “true Hollywood couple.”

Gary Nelson is now 82 years old. But he hasn’t lost any of his thirst for adventure. In the fall of 2015, Gary and his sons Garrett and Blue traveled to the parent Porsche factory in Zuffenhausen, about sixty years after the elder Nelson picked up a Speedster there in 1956. This time a 2016 718 Boxster S was waiting for them. The Porsche factory delivery team arranged to have the vehicle delivered directly in front of the Porsche Museum—and also placed a 1956 Speedster next to it. While Garrett remained behind in Germany, Gary and Blue set off on an exciting adventure. They drove across Europe to Gibraltar, crossed the strait to Morocco, and kept on driving across the northern Sahara to Algeria.

Blue Nelson began finding, repairing, and restoring classic cars as a teenager

“We simply set off—without an itinerary, without reservations, and without maps or a GPS. We just knocked on people’s doors and asked for directions,” says Nelson. When they returned to Stuttgart some 6,200 miles later, Porsche employees were astonished to see the amount of dust on the new car. The Nelsons flew home, and the blue Boxster was shipped to Los Angeles. Back home, Blue Nelson chauffeured his father in the white roadster to the Porsche dealership to pick up the new car. Still unwashed—by express request of the Nelsons.

Blue Nelson began finding, repairing, and restoring classic cars as a teenager in the 1980s. He kept some of them, but he sold many at car shows and auctions in California, where he soon made a name for himself as someone who could find “the rarest of rare cars.” Right from the start, he specialized in handmade aluminum car bodies based on VW frames, with names like Beutler, Dannenhauer, Drews, Enzmann, Hebmüller, and Rometsch. He stored them and then—in order to purchase a 356—sold a few when they increased in value. He was sixteen years old when he acquired his first Porsche, a 1958 356 A. “These models were still relatively affordable back then, because very few people were interested in them.”

By Nelson’s own account, his scouting has taken him to more than one hundred countries. And he continues to travel the world, rummaging through flea markets, peering over fences, onto driveways, and into sheds, and hiking to farms and across fields. His automotive detective and restoration work is a type of archaeology, often commissioned by a long list of prominent collectors. He doesn’t reveal any names, of course. His clients, who are involved in politics or the entertainment sector, require discretion.

Nelson is not one of those people who rattle off the technical details of their cars. He prefers to tell stories—of which he has an unlimited supply. Like the one about his Beutler. He acquired it in 1997 from a well-known banker in Manhattan in return for a Rometsch. For the trip back to southern California, Nelson didn’t load the silver legend onto a protected truck. Instead, he meandered across the country, covering 5,000 miles on highways and gravel roads, through dirt and sand, heat and rain. He slept on the car every night for a month, in a replica of a roof tent from the 1950s. And he fished for his dinner in rivers.

“I work eighteen hours a day, six days a week—and every once in a while I take one of my cars or motorcycles on a trip,” says Nelson. A stickler for detail, he pulls a bottle of water from a 1940s Philco refrigerator that is now powder blue, thanks to the leftover paint he used on a Volkswagen camper van. “But the aim is always the same—to preserve objects of historical interest.”

Nelson wants to preserve Joan DeWitt’s 356 in more or less the condition in which he found it in the garage. At some point he’ll put the technology back into shape by repairing the engine, transmission, and brakes. Will he polish the car body, or do a full restoration on it? Not a chance. “A fifty-minute wash would erase fifty years of work by Mother Nature,” he says. He’ll leave the exterior of the car in its “old and tired” state, including the dirt, spots, rust, and dust, and display it as is at car shows, amidst all the sparkling paint and polished chrome. He knows that people greatly appreciate seeing Porsches like this one. And that, in turn, can inspire them to find their own treasures in old garages.

Nelson’s first destination after fixing the innards of the 356 will be San Diego. Henry DeWitt had promised his wife Joan a ride in the Porsche. But he didn’t manage to get it running before he died. For Blue Nelson, a tour with Joan is a matter of the heart.

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 379

By Helene Laube // Photos by Linhbergh Nguyen

Consumption Data

718 Boxster S: Fuel consumption combined 8.1 – 7.3 l/100 km; CO2-emissions 184 – 167 g/km

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Porsche-356-(2).jpg)

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Porsche-356-1500-Coup%C3%87-(1953).jpg)

-and-his-father-(l.).jpg/jcr:content/b-Blue-Neson-(r.)-and-his-father-(l.).jpg)

.jpg/jcr:content/b-Rear-of-the-Porsche-356-A-1600-(1956).jpg)