The Cherangani Hills is just what they are called. Because “hill” is sheer mockery – these things look like the Zugspitze: 3,000 meters above sea level. The night from Maundy Thursday into Good Friday is pitch black, just as it should be out here in the wilderness. At the bottom of a slope Roland Kussmaul and Jürgen Barth are sitting in their Porsche packed full of spare parts. Kussmaul developed the rally cars of the type 911 SC for this safari, Barth wrote the master plan, according to which seven VW buses and two Land Rovers whizz across the country and keep both rally cars running along the 5,000-kilometre route.

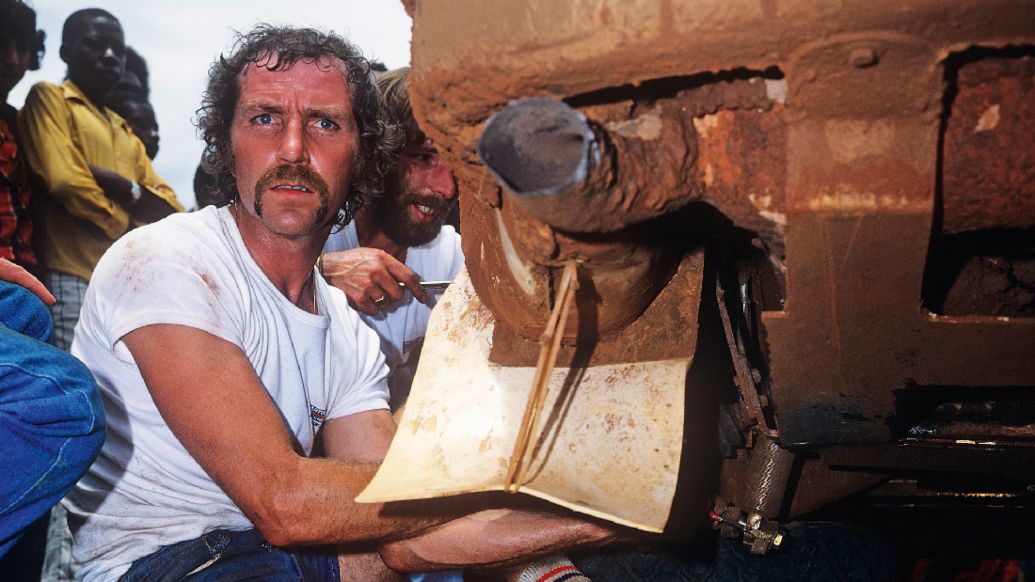

Now the two Porsche men are waiting for the Porsche 911 SC to appear with local hero Vic Preston Jr. and his co-driver John Lyall. Preston had reported by radio: “The front right shock absorber is broken!” Finally the three-litre naturally aspirated engine roars through the tropical night, the Porsche plunges down the steep gravel road, stops short at the time control, and rolls the final 50 metres across to Kussmaul and Barth. Kussmaul recalls: “We had to get the whole steering knuckle out because the damper wasn’t moving any more. Everything was so hot that we couldn’t touch anything. We told Vic and John to please move 20 metres away from the car. We had no water to cool down the damper, the brake and the wheel mount. So we tipped 20 litres of petrol over the whole thing and then did the repairs.”

The change is done in a flash, but to begin with it casts the Porsche with the start number 14 out of the top group after the first of three stages. The Swede Björn Waldegård had more luck over these first 1,800 kilometres in the works Porsche number 5. In the early night Waldegård’s 911 was among the five cars that managed to get over a river crossing before the floods became too torrential. The others waited for low water or drowned their cars. However, a second river crossing was very nearly the end of the previous year’s winner Waldegård: he drives in, the current catches the 911, the tail swings around like a boat in the rapids. Björn calmly keeps his foot on the accelerator and brings the Porsche safely to the shore. At midday on Good Friday, after a long, wet night as the leading man he comes back to Nairobi, where the chase will continue on Saturday shortly after sunrise. A short break for the works teams of Porsche, Peugeot, Mercedes and Datsun; also a chance to take a breath for the dozens of willingly suffering rally amateurs and their battered equipment.

Overnight the rally cars rest in the large square at the Kenyatta Conference Centre in the middle of Nairobi. The Peugeot 504 V6, the Datsun 160 J, the Violet and Mitsubishi – at first glance family cars which nonetheless all have one thing in common: infinite can-do qualities – a toughness that they need here. In 1974 a Lancer pushed Björn Waldegård in the Carrera RS into second place, and in 1975 a 504 defeated the super rally car Lancia Stratos. Mercedes now brought out the 280 SE, but weighing in at two tons it seemed too heavy.

Heavyweight cars can spontaneously break down on the hair-raisingly brutal slopes and 200 hp seems meagre for two tons. With an unladen weight of 1,180 kilos, the 911 SC Safari developed by Kussmaul, on the other hand, seemed highly promising. The kilos are combined with 250 hp from the tried-and-tested three-litre naturally aspirated motor of the type 911/77, which had already powered the 911 RS and RSR drive since 1974/75. A six-millimetre aluminium underguard runs from front to rear. Kussmaul: “Because of the short wheelbase, the car nodded and dipped heavily. A large stone at the wrong moment could have seriously damaged the exhaust manifold or the engine. In addition, the car can glide through deep mud or dust on the aluminium as if it’s on skids.”

The vehicle body and chassis are reinforced, the rear axle swing arms made of die-cast aluminium armoured with two layers of CSF and 1.5 mm steel plate. The engine cover is sealed with foam tape, because “...the fine dust wears down even the piston rings. We therefore made sure that the engine only took in air through the grill above the ducktail. Behind the spoiler there was so much dust due to the turbulence.” The clutch is modified for rough use, the transmission was given an extra oil cooler and a slightly extended fifth gear by Kussmaul. 28 centimetres of ground clearance and large spring deflections are the hallmarks of the reinforced Africa chassis. Massive wipers protect the steel brake callipers from mud, which rubs them smooth during test runs in Kenya. Typical rally supplies include the roll cage, two spare wheels – one under the front lid, one behind the seats – a huge jack, a 110-litre petrol tank and 16 litres of windscreen washer fluid on board. Needless to say, Kussmaul tested the Safari car with countless test kilometres on the tank test site and speedy driving over buried railway sleepers in Weissach.

The Saturday arrives and brings Björn no luck. After 2,500 kilometres – that is, at the halfway point – he is still leading the field, when in the Taita Hills on the way down to the Indian ocean a rear axle swing arm gives up the ghost despite its armour. It takes Kussmaul and Barth almost an hour to reach the broken down vehicle along the mountain tracks in the training 911 converted into a speedy spare parts store. The repair is completed in record time, but they’ve lost the lead. Later, Waldegård and his co-driver Hans Thorszelius encounter a low-flying vulture. The scavenger is hovering at almost exactly the height of the windscreen when the Porsche hits it. Kussmaul: “When we reached Björn, there were a few parts of the vulture in the back of the car and they smelled quite strong. But mainly the bird was stuck to the windscreen.”

Thanks to quick-release fasteners, in a few minutes Waldegård’s car was fitted with the windscreen of the Kussmaul/Barth Porsche. The journey continued, with Kussmaul and Barth now roaring through the night at 180 km/h without a windscreen, but with motorcycle goggles on: “You wouldn’t believe how much it hurts when a beetle the size of your thumb hits your face at 180 km/h”, Kussmaul recalls. The new windscreen soon arrives from the air: above the drama of the Safari, a Porsche-chartered plane is circling.

The head of motorsport Peter Falk and the leader of the attempt Helmuth Bott take it in turns on board. They squat over stacks of cards and Barth’s service plan, give instructions by radio and have larger parts on board. Barth radios Falk, who asks the pilot if he can land on the road below. No problem, says the pilot. Barth and Kussmaul block the road, and the Cessna lands. Everybody celebrates, has a quick chat, then continues on their way.

Raging rivers, impassable mud holes, roads washed away: the way back to Nairobi is arduous. In half an hour Waldegård repairs a broken shock absorber himself. Preston, meanwhile, has had his foot pressed down keenly on the accelerator pedal and arrives back in Nairobi in third place behind two Datsuns.

On Easter Sunday at 4:00 pm the curtain rises for the final act. Heading north-west from Nairobi, the rally first plunges down into the oven of the Rift Valley, where Waldegård’s throttle linkage is repaired for 45 minutes. Then the Safari climbs up the Mau Escarpment up to 3,000 metres and continues north to the town of Isiolo, where the Trans-African Highway leads into infinity. This is where mere mortals enter their names and number plates in a book in case they get lost in the savannah.

At the end only 13 of 72 cars will be left in the ranking.

Preston loses time by twice having to change a half shaft. But the Safari is not only hard on the Porsche drivers: at the end only 13 of 72 cars will be left in the ranking. Timo Mäkinen bows out with his Peugeot on the way back to Nairobi due to half shaft damage. The leader Harry Källström causes his Datsun to fall apart on landing after an over-optimistic long jump; parts of the wreckage were apparently flung more than 300 metres.

Rauno Aaltonen is driving another 160 J as if possessed and is closing in on the now leading Jean-Pierre Nicolas, until his co-driver sends him on a detour in the wrong direction. And so they fall into place.

Nicolas is six kilometres from the finish line when a local suddenly decides to perform a turning manoeuvre right in front of the Peugeot. The 504 is badly dented on the front and engine coolant gushes out. Nicolas puts his foot down and brings his wreck to victory ahead of Preston Jr., who needed 37 minutes longer for the 5,000 kilometres. Björn Waldegård takes fourth place. Porsche bids farewell to its Safari adventure. But the topic of “Africa” is not finished with. A few years later, first a 911 and then a 959 win the 14,000-kilometre rally from Paris to Dakar. The person responsible for the cars is Roland Kussmaul.

Porsche 911 SC Safari

Engine: 911/77 six-cylinder flat engine

Displacement: 2,994 cm3

Bore x stroke: 95 x 70.4 mm

Maximum power: 250 hp at 6,800 rpm

Power transmission: 915 five-speed modified, differential lock

Unladen weight: 1,180 kg

Info

Text first published in the magazine "Porsche Klassik 13".

Text: Wilfried Müller // Photographs: McKlein Photography

Copyright: The image and sound published here is copyright by Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG, Germany or other individuals. It is not to be reproduced wholly or in part without prior written permission of Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG. Please contact newsroom@porsche.com for further information.