He beat them all up. Anyone who made fun of his red hair. “I didn’t let them get away with anything. That gave me strength for the rest of my life,” says Walter Röhrl, who was usually allowed to leave school in the Bavarian city of Regensburg ten minutes before class was over at the end of the day. His teachers were too concerned that he would be teased and respond by landing some well-placed blows. And he’s kept that boldness into adulthood. “At the Monte Carlo Rally I showed them who’s boss!” There’s only one person who’s ever been able to dictate his course—codriver Christian Geistdörfer, with whom he entered rallies from 1977 to 1987.

The two men could not be more different. One is defiant, the other diplomatic. One of them curses up and down the alphabet at the slightest hint of injustice—“and you can hear it a hundred meters away,” says the seventy-one-year-old Röhrl. And the other prefers to reflect until he finds a thoughtful solution. What they share is an unconditional trust in each other. “In the cockpit, we’ve each placed our lives in the other’s hands,” says the sixty-five-year-old Geistdörfer.

Mille Miglia was considered the toughest race in the world

Today’s Mille Miglia is no longer a matter of life and death. From 1927 to 1957 it was considered the toughest race in the world. But now “the Mille,” as Röhrl calls it, is one of the most high-profile rallies for vintage cars. The winner is not the vehicle with the fastest time but rather the team that collects the fewest penalty points over the course of more than eighty special trials as well as passage and time controls. A contest of consistency.

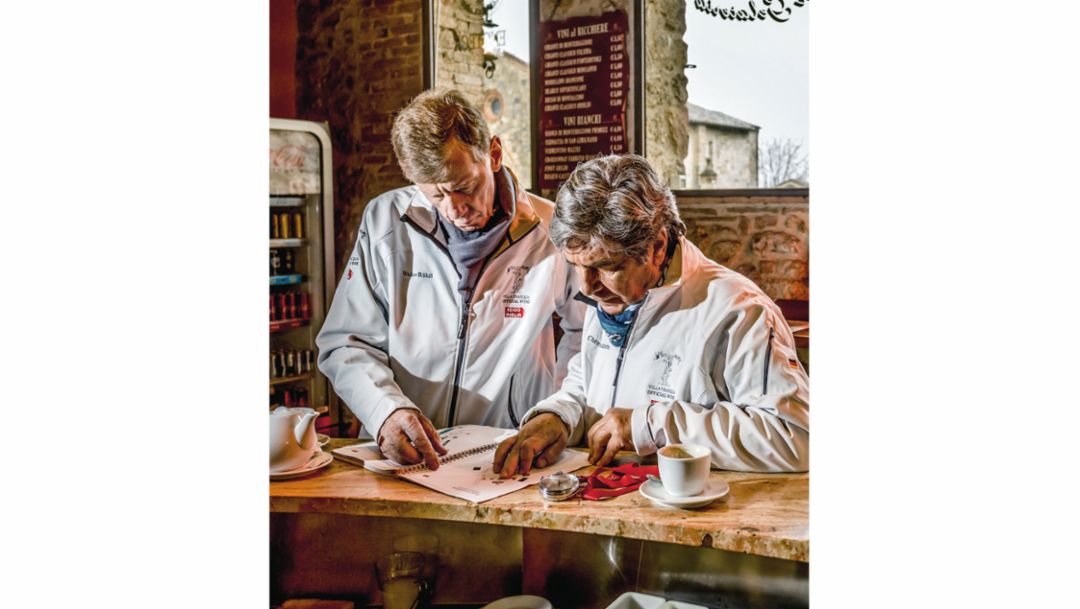

When the Mille Miglia was launched ninety-one years ago on March 26, 1927, the aim was to drive at top speed from Brescia to Rome and back—in a single day on what was then a figure-eight-shaped course. Today the 450 teams have four days to cover the route, and a road book to guide them through the countryside. On May 16 Röhrl and Geistdörfer will enter the event in Brescia in a 1956 Porsche 356 A 1500 GS Carrera Coupé. A few weeks beforehand, they meet near the route in Tuscany to get in the mood for the rally with their Sahara Beige vintage automobile. And they begin to reminisce.

Röhrl carefully opens the door of the car and bends down to stick his head inside. He strokes the burgundy driver’s seat and the beige interior lining. Then he folds his 1.96 meter frame and climbs in. After closing the door he crosses his arms in front of his chest as if seeking to prevent himself from driving off right away. He enjoys the stillness for a few minutes. And smiles.

“230“ – starting number for race-car driver Carel Godin de Beaufort in 1957

Meanwhile, Geistdörfer walks around the restored vintage car and takes a photo of the stickers on his side of it. They show “C. Geistdörfer” holding a stopwatch and “W. Röhrl” with a steering wheel underneath. The hood and the doors display the number 230. That was the starting number for Dutch race-car driver Carel Godin de Beaufort at the Mille Miglia in 1957. Seven years later he died in an accident on the Nürburgring. The owner of this Porsche 356 A 1500 GS Carrera Coupé is Hans Hulsbergen, a native of Switzerland with Dutch roots. He’s a friend of the de Beaufort family and wanted to commemorate Carel in this way. “The car has matching numbers, is beautifully restored, and it’s an honor for us to drive it,” says Geistdörfer, putting his excitement into words.

Röhrl places his big hands on the slender wooden steering wheel and slides his thumbs up and down. His left hand is at the ten o’clock position and his right hand at two o’clock. Although he’s driven nearly every Porsche model, this is the first time he’s ever sat in a 356 A 1500 GS Carrera Coupé. Geistdörfer has now circled the car four times, opened the luggage compartment, coiled up a battery charging cable, lifted the hood, and peered into the fuel tank with a flashlight. He’s a professional codriver who takes care of everything, while Röhrl “only” has to drive. That’s the way it’s always been. And the way it should be.

They exchange nods and Geistdörfer gets in. “We’re extremely good at being silent together,” says Röhrl. “We might be in the car for twelve hours and spend hardly ten minutes in conversation. Christian gives directions the whole time. When he’s not doing that, it’s just good to hear the sounds of the car.” They’ve never quarreled. And Geistdörfer has never misread the route. “I’ve always told Christian that a codriver is only allowed to misread the route twice—the first time and the last time,” says Röhrl with a grin.

Geistdörfer: “A codriver has to (...) possess unusual presence of mind”

After entering rallies, Geistdörfer would often spend a few days of vacation in the country where they were held. Röhrl, by contrast, “always wanted to go straight home.” They don’t share much personal information with each other. “When Walter wanted to tell me something, he did. I never pried,” says Geistdörfer. “I have great respect for Christian, and that’s why I’ve always been reserved,” says Röhrl, who learned a number of things he had never known about his codriver upon reading the latter’s recently published biography. And although they still greet each other with a handshake instead of a warm hug, each describes the other as a friend, not just a business partner. “A codriver has to not only read maps correctly but also be quick on the uptake and possess unusual presence of mind,” says Geistdörfer. “But the most important thing is to have unshakable confidence that the person sitting at the wheel next to you also wants to survive the whole crazy endeavor. I’ve always admired Walter’s singleness of purpose. And if it crossed over into stubbornness, I could see where he was coming from. My job was always to prevent problematic situations from arising in the first place.”

They used to go skiing together, but “since Walter started insisting on walking up the slopes, I don’t join him anymore,” says Geistdörfer with a laugh. Röhrl, whose fans call him der Lange (the tall one), hasn’t used a lift in years. He tells the following anecdote, punctuating it with a raised index finger: “In Portugal at the Arganil stage in 1980 I left everyone way behind in thick fog. Visibility was less than five meters. No one could believe it was possible to drive 4:58 minutes faster than the next car. I was able to do that because of my photographic memory, but also because I was fit.” He never takes escalators and swims laps every morning in his own pool. “Otherwise I feel like I’m a hundred years old,” he remarks. He steps on the scale every day. “If my weight ever goes up by 450 grams, I swim longer or walk faster up the slopes.” Röhrl, who’s known for his ascetic tendencies, has never indulged in a Coke or a coffee.

In the 1980s it wasn’t unusual for Geistdörfer to pull out the fuses for the rear lights on foggy nights to prevent the drivers following them from using their path. “I prepared the fuses beforehand with aluminum foil so I could just barely reach them without removing my seat belt,” he recalls with the steely will to win still evident in his eyes. Were they ever afraid? “At the beginning of every race I was always sure that nothing would go wrong and that we were invincible. In retrospect that was totally stupid,” says Röhrl, shaking his head. What was the most dangerous course? “Pikes Peak. Back then it was all gravel. There wasn’t anything you could use for orientation, just a few trees at the beginning that was it.”

Humorous situation during the Monte Carlo Rally in 1983

The duo encountered one dangerous yet also humorous situation during the Monte Carlo Rally in 1983. “Someone handed us a few oranges at a time check. I put them on the back seat and promptly forgot about them. But then later I tried to brake only to find that they had rolled under my pedals, right in the middle of the twenty-minute special stage from Le Moulinon to Antraigues! I managed to collect all of them after about seven minutes. At full speed. And we won the stage by three seconds.”

Röhrl, who’s a qualified ski instructor, reflects back on his driving style. “I’ve always steered very little. That doesn’t put on a great show for the spectators, but it made me the fastest. It’s similar to skiing. When you throw up a lot of powder it looks great, but you can be sure it’s not the best line.”

In September Röhrl will celebrate fifty years of racing. He started his career at the Rally Bavaria at the urging of a good friend. Shortly thereafter he quit his job as an administrative assistant for the Diocese of Regensburg—“no, I was never the personal chauffeur for the bishop and have no idea how a rumor like that can stick around for decades”—to focus on a single aim: “I wanted to win the Monte Carlo Rally.” He did so four times in the five-year period from 1980 to 1984, because of his ability to drive equally well on snow, gravel, and asphalt. “Every surface has pros who specialize in it, but I was the only one to master the racing line for all of them,” he recalls. Röhrl leans back and closes his eyes. “My first win in Monte Carlo was in 1980, and that was the most beautiful moment of my career.”

Geistdörfer is looking forward to the fun atmosphere

Geistdörfer has entered the Mille Miglia five times without Röhrl, and Röhrl once without Geistdörfer. What do the two of them expect from their first Mille Miglia together? “We’re driving in one of our favorite countries,” says Röhrl. “Not least of all because the Italians are so wonderfully crazy about cars. They love their Mille.” Geistdörfer is looking forward to the fun atmosphere and the scenery. He’ll arrive a day earlier than Röhrl in order to be there for the technical inspection and the traditional sealing ceremony. They already know that they won’t win, because their sixty-two-year-old Porsche is too young. “Prewar cars are assigned a coefficient that improves their chances—although they’re also harder to handle,” says Geistdörfer. And Röhrl adds, “The slow windshield wipers on the 356 are the first step toward deceleration.”

How long will Röhrl go on driving? “Until they pull the plug,” he says with a laugh as he drives the Porsche under the stone archway in the old city wall of Monteriggioni. For a moment it appears that nothing in this world could keep him from racing. “Oh look, a cat!” he cries. He pulls the car to a stop and climbs out to stroke the purring animal at the side of the road.

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 386