The two racing cars belong to the circle of stars at the “Porsche Rennsport Reunion VI” – the world`s biggest meeting of historic and current racing and road going Porsche cars. The sixth edition of this extraordinary event is taking place this weekend at the Californian Laguna Seca Raceway, south of San Francisco.

Extreme athletes of two eras: 919 and 917

The 919 Hybrid and the 917 dominated the races of their time. From 2015 through 2017, the hybrid racing car won the Le Mans 24-hour race three times in a row as well as the FIA World Endurance Championship WEC for manufacturers and drivers in the respective years. It was the 917 that secured Porsche its first two – of what has become a total of 19 – outright Le Mans victories back in 1970 and 1971, and helped the marque win the manufacturers’ title in the World Sportscar Championship the same years. In both cases, for the 919 and the 917, technical regulations influenced the decision to withdraw from the respective World Championships. The situations, however, were different: For the 919 further hybrid innovations, which would have been relevant for road going cars, were ruled out. Back in 1972, the 917 domination was so stifling that motorsport authorities banned its five-litre twelve-cylinder engine.

However, instead of heading straight to the museum, both cars experienced strong developments for a second career.

Record chasing at the Nürburgring’s Nordschleife and in Talladega

The Youtube video has hit over 2.7 million views to date: The on-board recording of Timo Bernhard’s record lap around the Nürburgring’s Nordschleife, or north loop, is not for weak nerves. The two-time Le Mans winner and endurance world champion from Germany lapped the legendary 20.8-kilometre course in the Evo version of the Porsche 919 Hybrid in 5:19.dd minutes on June 29 in 2018. The 37-year old attained an average speed of 233.8 km/h in the “Green Hell” and a top speed of 369.4 km/h. The world of Formula One sent its congratulations. It was already familiar with the Evo: back in April, Swiss driver Neel Jani had beaten the F1 track record in Spa-Francorchamps, Belgium. In August, however, F1 retrieved the record at the track known as the Ardennes Rollercoaster. The Evo is an advancement of 2017 Le Mans winning car. At the end of its outstanding career, engineers unleashed the car from the restrictive rules to let it really show what it can do.

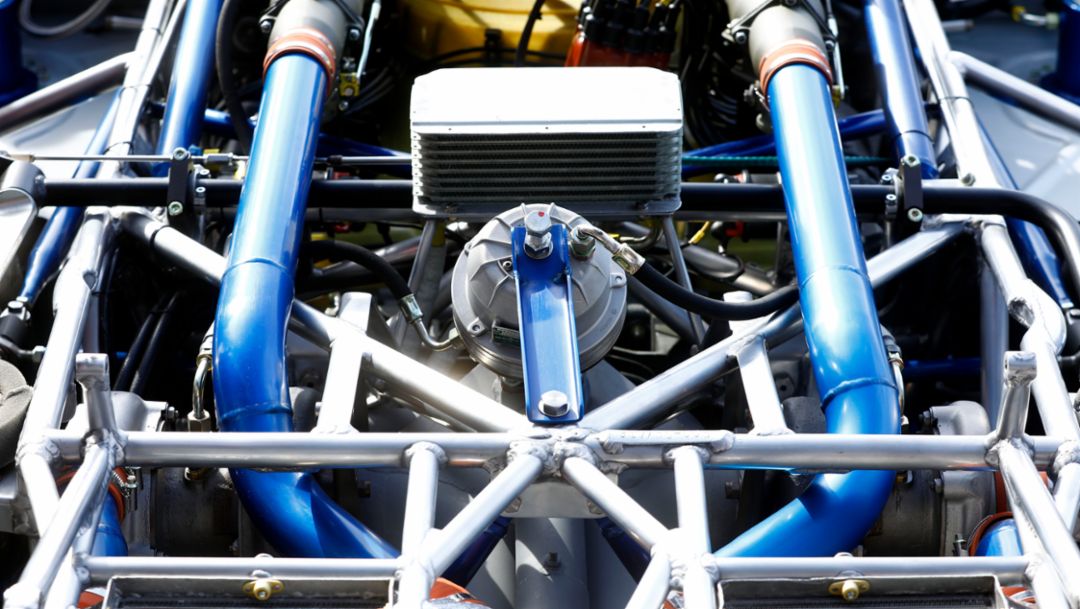

A genetic predisposition also played a role in the origin of the Evo. Once before, in 1973, Porsche turned a victorious vehicle inside out: the 917 became the 917/30. The 917 had racked up fifteen endurance victories by the time it wasn’t allowed to take part in the world championship any longer, and its first evolution happened to continue racing in oversees. North America had become the brand’s largest individual market, and the Canadian-American Challenge Cup, or CanAm for short, became an attractive racing series. In order to be able to compete against the dominant McLarens and their 800 hp V8 engines from Chevrolet, the V12 normally-aspirated engine of the 917 was not enough. Performance improvement by turbocharging was still largely uncharted territory – but one that Porsche now explored. Among the pioneers was American Mark Donohue, a successful racing driver and engineer, 34 years old at the time.

In 1972 the approximately 1,000 hp 917/10 TC Spyder (TC stands for turbocharged; Spyder refers to the now-open cockpit) won six CanAm races and the title. As competition upgraded for the 1973 season, Porsche presented its answer: the 917/30. Donohue’s ideas for improvement didn’t even leave the wheelbase untouched, lengthening it from 2,310 to 2,500 millimetres. An elongated front and a significant extension of the rear wing were also added – aerodynamic measures with which Porsche had not yet had much experience. At Le Mans, aerodynamic drag had to be reduced as much as possible to increase top speed on the long straights. Now downforce was the order of the day to transfer the monumental engine power to the road surface. The V12 now provided the 800-kilogramme Spyder with 1,100 hp and the response behaviour of the turbo was tricky. Meanwhile enlarged to 5.4 litres, the engine released its power late and with tremendous force. Porsche applied several detailed solutions to get to grips with the turbo lag. Sitting in the Spartan cockpit, Donohue could now turn a boost controller to domesticate the V12’s manifold pressure. For the race start he’d turn up the pressure to reduce it later to save the engine and fuel. The V12 was a thirsty one, which was why the gasoline tank of the 917/30 could hold up to 440 litres.

In 1973 Mark Donohue won six out of eight races in the CanAm series and took home the championship title. Then once again regulation changes meant the superior race car was suspended. But on August 9 in 1975, the 917/30 gave one last brilliant performance: on the 4.27-kilometre Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama (USA), Donohue’s average speed of 355.78 km/h (maximum speed 382 km/h) set a world record that stood for eleven years. Thanks to charge-air intercoolers, used here for the first time, the V12 achieved 1,230 hp.

The 917 wasn’t designed for the steep oval and neither was the 919 Hybrid made for the Nordschleife. The parallels stretch from world premier to world record: both cars were presented at the Geneva Motor Show, the only two occasions where Porsche placed a racing car at the centre of its brand profile. Both were the known as the most innovative racing cars of their time and the creation of both took a considerable dose of courage. This applies to Ferdinand Piëch’s determination to build the 25 examples needed for the homologation of the 917 in 1969 – despite financial risks – as well as to the 2014 decision of the Porsche Executive Board to return to Le Mans and the World Endurance Championship with a technologically highly advanced hybrid vehicle.

Unlike with the development of the 917/30, for the Evo version of the 919 the hardware in the drivetrain remained untouched. The V4 turbo, whose capacity is only 2.0 litres, continues to drive the rear axle – without, however, the fuel consumption restriction to which it was subject when competing in the WEC. Thanks to this freedom and some software support, the Evo’s combustion engine attains 720 hp instead of previously 500 hp. The two energy recovery systems provide massive support by collecting brake energy on the front axle and – by means of an additional turbine – energy in the exhaust tract and storing it temporarily in a lithium-ion battery. Where the WEC regulations limited the deployable quantity of energy from these systems, the technology in the Evo could use their full potential for the record attempts. The e-motor that drives the front axle – and which makes the 919 temporarily all-wheel-drive – now contributed 440 hp, ten per cent more than in the WEC. The result is a system output of 1,160 hp at a vehicle weight that has been reduced from 888 kilograms (including the driver ballast) to 849 kg.

The upgrade for chasing records also included a brake-by-wire system for all wheels, stronger suspensions and specially developed Michelin tyres to withstand higher aerodynamic forces. The larger front diffusor and the big time rear wing are also equipped with active aerodynamics. Similarly to Formula One, drag reduction systems are used to sat the wing elements flat in order to reduce air resistance on straight stretches. Together with an aerodynamically optimised floor and lateral skirts, the Evo generates 53 per cent more downforce than the 919 did in the WEC. “As if on rails”, is how Timo Bernhard described the feeling of driving through the fast corners at the Nordschleife. Donohue could only have dreamed of a dynamic behaviour like that during his daring ride in Talladega.