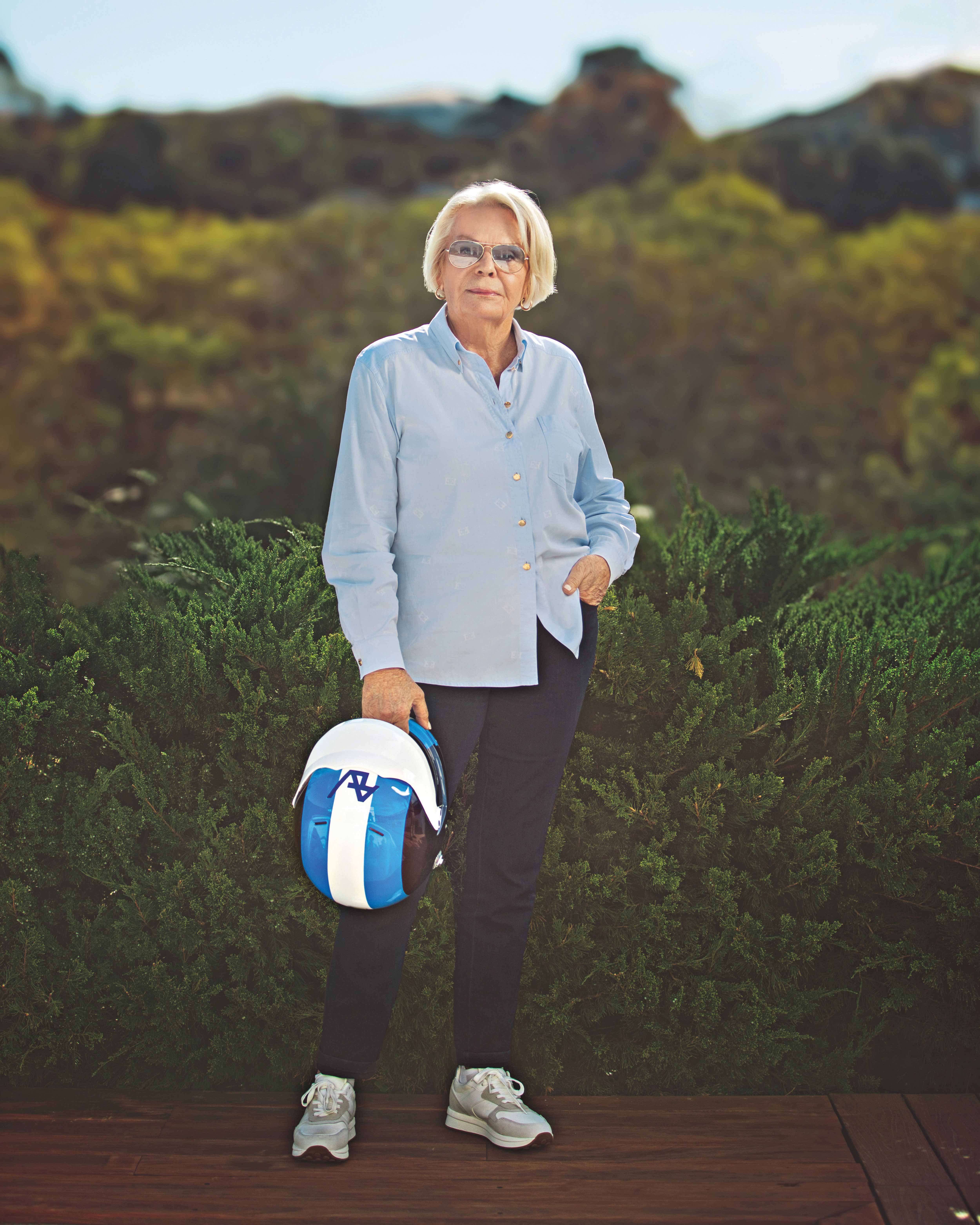

“I’ve always done what I wanted,” says Anny-Charlotte Verney. The queen of Le Mans is out on the patio of her row house near Biarritz. She’s 81, is wearing light-blue tinted aviator glasses, and sounds amused. As if she herself were amazed at everything she has achieved in life.

There was no holding her back

She was just telling the story of how she came up with the idea of becoming a race car driver. It was in 1949. Her father Jean-Louis François Verney took her to the 24 Hours of Le Mans, held in her hometown. He was Vice President of the race organizers, the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO). “One day, I will compete alongside them,” declared Anny-Charlotte, who was six years old at the time.

Her father dismissed her announcement with an affectionate “Oui, oui.” Her mother’s reaction a few years later at a fashion show was not dissimilar. “I will be doing that one day, too,” said Anny-Charlotte, pointing at the models. “Sure,” said her mom, not believing a word of it. Both of her parents should have known better because when the younger of their two daughters got something in her head, there was no holding her back. “When I say I will do something, I do it,” says Anny-Charlotte Verney in the present day.

“I’ve always done what I wanted.” Anny-Charlotte Verney

She left home aged 21, attended a modeling school, and was soon modeling for brands like L’Oréal and Hermès. She spent four years traveling around the world as a model. Then she came back to her career aspiration of old and applied to the “École de pilotage Bugatti” driving school in Le Mans. At the same time as 149 others. Anny-Charlotte was the only woman. It was understood that only the top 50 would be allowed to advance. “Well, she’s got the looks,” some of her competitors prophesied gloomily. Others said she was only being considered because of her name – not only was her father a Le Mans legend, her grandfather was even more of one: Louis Verney was one of the race founders in 1923. She finished in ninth place and, after completing her training, was selected to join Citroën to drive a one-seater Citroën MEP race car for a season in 1972.

She couldn’t exactly claim to be otherwise bored either – alongside her sporting career, she worked at her parents’ freight company. She also gave birth to a son in 1970 – the first of three children. And continued to race.

The debut

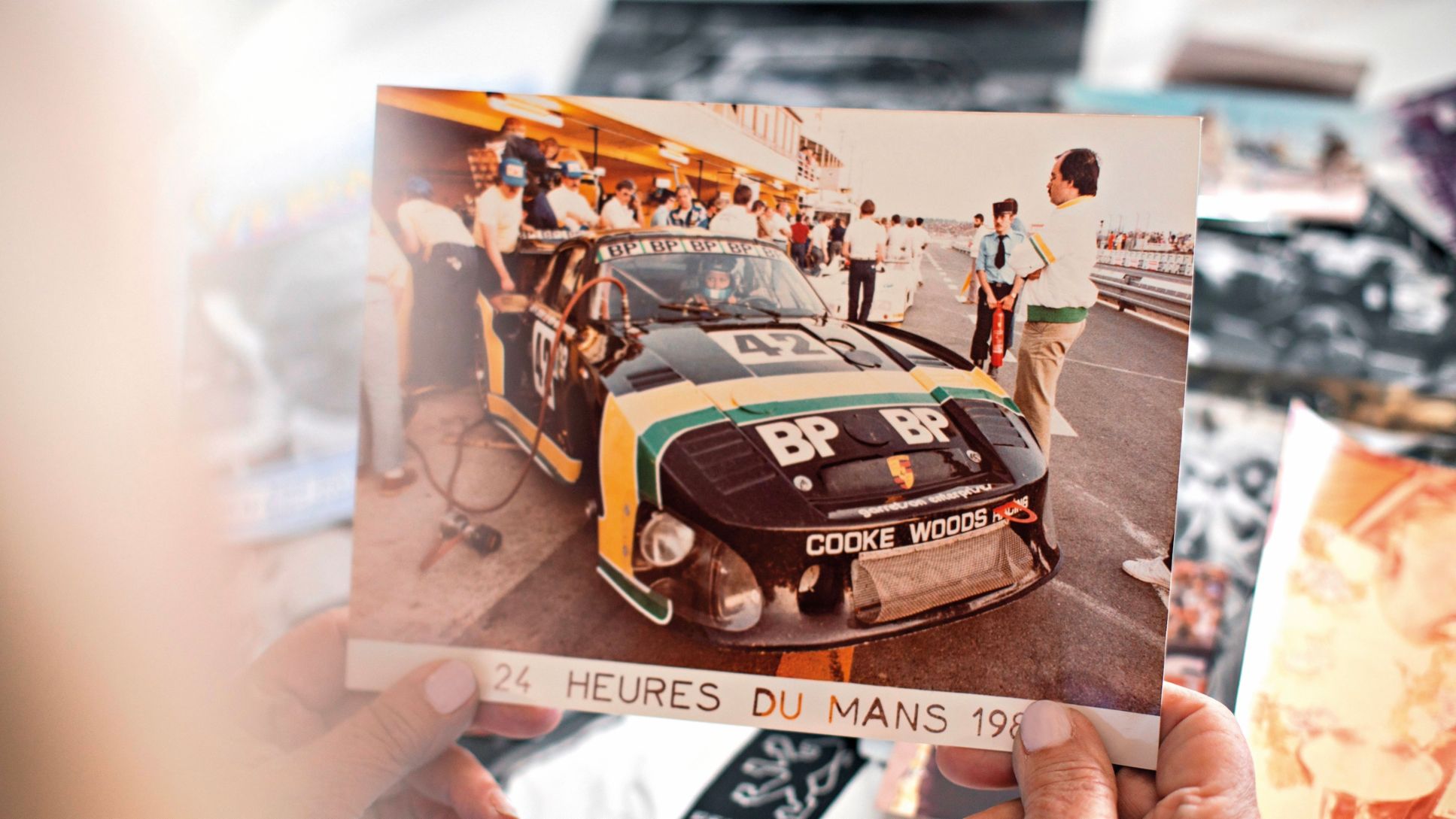

In 1974, her sponsor offered her a huge opportunity: BP included her in their lineup for the race in Le Mans. She was to drive a Porsche 911 Carrera RSR. Her parents read about it in the paper.

Her father, a level-headed man by nature, almost had a heart attack. Right before the race, he begged her: “If you feel like it’s getting too fast for you, please pull out!” “Sure thing, Pop,” joked Anny-Charlotte, “I’ll just put my warning lights on and stop at the end of the straight.” By this, she meant the Mulsanne Straight, the section where the fastest speeds are achieved.

On the starting line with all the cars bunched up close together, her heart was racing. “What am I doing here?” she kept asking herself during the first two or three laps. But then she settled into a rhythm. She thinks back to that feeling of happiness: four o’clock in the morning, the air now cooler, and the car running like clockwork. “That night was better than a night with any man.”

Ask her what she loved about the competitive events and she says “la bagarre” – the fight: “I wanted to win!” And what about fear? “When I was driving, I was so focused that I didn’t notice it.”

She’s now sitting in her bright living room. Next to the sofa hangs a painting of a fisherman from the Caribbean, next to the dining table a picture of her on the Le Mans racetrack. She has scattered photos across the table. In one of them, her father is presenting her with a trophy. Another features her grandfather Louis with a twirly mustache. He didn’t get to witness his granddaughter’s career, as he passed in 1945. It’s said in the family that she inherited his vivacious character.

10 times at the 24 Hours of Le Mans

There is a shelf full of her trophies. Verney’s successes in Le Mans include her 1978 GT class victory in a Porsche 911 Carrera RSR and her sixth place overall in 1981 in a Porsche 935 K3. She achieved her personal top speed of 358 kmh in the latter. She entered the 24-hour race 10 times – more than any other woman. On nine of these occasions, she was behind the wheel of a Porsche: from the 911 Carrera RSR and the 935 K3 to the Carrera RS and the 934.

“A Porsche is a Porsche,” she says in recognition. She says there is no better, more reliable car for races such as Le Mans and Daytona, where she likewise competed. And that’s just one of the reasons why she doesn’t own a Porsche now, she explains: “I’d like to keep my driver’s license!” she says, grinning. France has strict speed limits.

Axle breakage in the desert

Talking of which, it’s time to jump in the car. Verney has reserved a table at a golf club for lunch. She only puts her seat belt on when the car warns her to with a loud beeping sound while she is driving. She has no time to waste at the start.

On the golf club patio that offers a view of the club’s greens and the blue Atlantic, she talks about the adventures she had between Paris and Dakar. She entered the famous desert rally 10 times, as well as other African rallies in various vehicles, albeit none of them coming from Zuffenhausen. On her first time competing in the Dakar Rally in 1982, she had a well-known codriver – Mark Thatcher, son of the British Prime Minister at the time.

They were unfortunate, though, as they suffered a rear axle breakage in the middle of the Algerian Sahara just a few days into the event. But even more seriously, they had diverged from the route. The temperature fell to minus five degrees Celsius overnight, and rose to close to 40 degrees during the day. And there was nothing around them – just red sand, the odd bush, and the question of whether they would be found. Verney, Thatcher, and the mechanic only had one day’s rations to eat and drink.

As the search parties headed out, the three of them were taking their last sips of water. Later, they emptied their car’s coolant, and Anny-Charlotte even drank her perfume. It took six days for them to be found. “Two more days and that would have been it,” she believes.

“Two more days and that would have been it.” Anny-Charlotte Verney

She nevertheless went on to compete in the rally another nine times. Accidents never kept her from sticking at it either. She suffered multiple fractures in the Bandama Rally in Côte d’Ivoire in 1973 and only just survived. In the 1990 Paris–Dakar Rally, her car rolled seven times and was “flat as a crepe” afterwards. “C’est la vie,” she shrugs, “that can happen when you engage in such a sport.”

Her last race was in 1992. When she found herself wondering: “What am I doing here?” for the second time in her life somewhere between Paris and Cape Town, she no longer had a positive answer. It was time to call it a day. She then spent 10 years in the Dominican Republic, before moving to Florida. She has since moved back to France and naturally travels to Le Mans every year for the race.

You might say she continues to do what she wants. She plays golf three times a week, practices Pilates, and conducts business. If she feels like it, she jumps in her car and drives to Spain to visit friends or her son and grandchildren. “What more could I want?” asks the queen of Le Mans, saying goodbye with a firm handshake. It’s nearly 4 p.m. – the time at which the race in her hometown always starts.

Info

Text first published in the Porsche magazine Christophorus 411

Author: Andrea Walter

Photos: Céline Levain, Porsche

Copyright: All images, videos and audio files published in this article are subject to copyright. Reproduction in whole or in part is not permitted without the written consent of Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG. Please contact newsroom@porsche.com for further information.