A mural extending more than 15 metres in length and three in height hangs on a wall. By the British artist Grayson Perry, it is an epic interpretation of William Shakespeare’s Seven Ages of Man, weaved using an old Sumatran technique out of 14 different shades of thread and depicting the different stages in the life of a man. In front of this all-encompassing work of art stand two Porsche 356 cars. Welcome to the garage of architect Lord Norman Foster. At 85 years of age, he remains a live wire with a firm grasp on the wheel. We look at a life in seven acts.

Act one – Manchester

June 1935. Norman Foster is born in Stockport, England. He grows up in the working-class city of Manchester. As a child, he writes an essay that wins him a place at a high school. The essay describes a racing duel on the Nürburgring. “I realised I was fascinated by race cars. Especially Porsche’s designs with rear-wheel drive,” he recalls. “For me these cars are works of art like futuristic sculptures.”

For financial reasons, Foster leaves school at the age of 16, taking a job at an agency. Books and magazines are the primary source of inspiration in his youth. The Eagle, a maverick weekly mixture of futurism, technology and architecture, features Dan Dare on its cover. This comic-book hero is a pilot. Foster begins to dream of flying. His first adventure born of science and fiction will soon become reality.

Act two – the Royal Air Force

Foster’s passion for flying prompts him to do military service with the Royal Air Force. Although his everyday tasks at a radar station are on the ground, years later he earns his first pilot’s license. Aircraftsman Foster 2709757 continues to fly helicopters and jet planes to this day. After his military training, he needs a job and there’s no way he wants to return to the joyless atmosphere of the agency. He finds his next great inspiration in a library in Levenshulme, and treasures Le Corbusier’s book Vers Une Architecture to this day. “I was hypnotised by the designs,” he says.

His application portfolio for the architecture program at the University of Manchester is accepted. A bold design for a windmill earns Foster an award when he’s only in his second semester. The design for a house with a motorboat docking almost in the living room is another example of how he stands out from his fellow students.

Act three – Yale

In 1961, Foster wins a fellowship at Yale. American architectural treatments of form and function have long since caught his attention. In the lead-up to the Second World War, many leading European thinkers had left the continent and were making their multi-story dreams come true on the other side of the Atlantic. They included greats such as Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Foster enjoys his time at Yale. Visionaries like Richard Buckminster Fuller and Paul Rudolph drive him to new heights of performance. Foster and fellow student Richard Rogers drive a Volkswagen Beetle across the USA, drawn as if by magic to buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles Eames. Structures based on modular systems leave a lasting impression. After completing his degree at Yale, Foster works for a few months in San Francisco. There he falls in love with the lines of the Porsche 356. “The car had a cult status in California. It was actually a niche product, but every time I took my MGA in for servicing, there were a lot of them around. Even the head designer at my office drove one. I was immediately fascinated by the form and the idea of this car.”

Act four – Team 4

Foster, Richard Rogers, Foster’s future wife Wendy Cheesman, and her sister Georgie found the Team 4 architectural office in 1963. One of the first designs wins the RIBA Award from the Royal Institute of British Architects – and memorialises Foster’s passion for flying. One part of the award-winning Creek Vean house in Cornwall, England, evokes a cockpit partially submerged in the ground. With their mixtures of traditional and industrial materials the four architects stand out from the mainstream, and their work even finds its way into movie theatres. Film director Stanley Kubrick uses Skybreak House in the English town of Radlett in 1971 to shoot his blockbuster A Clockwork Orange.

Act five – Foster + Partners

Foster and his wife Wendy found the Foster Associates architectural office in 1967, which they later rename Foster + Partners. It becomes a source of visionary architectural art.

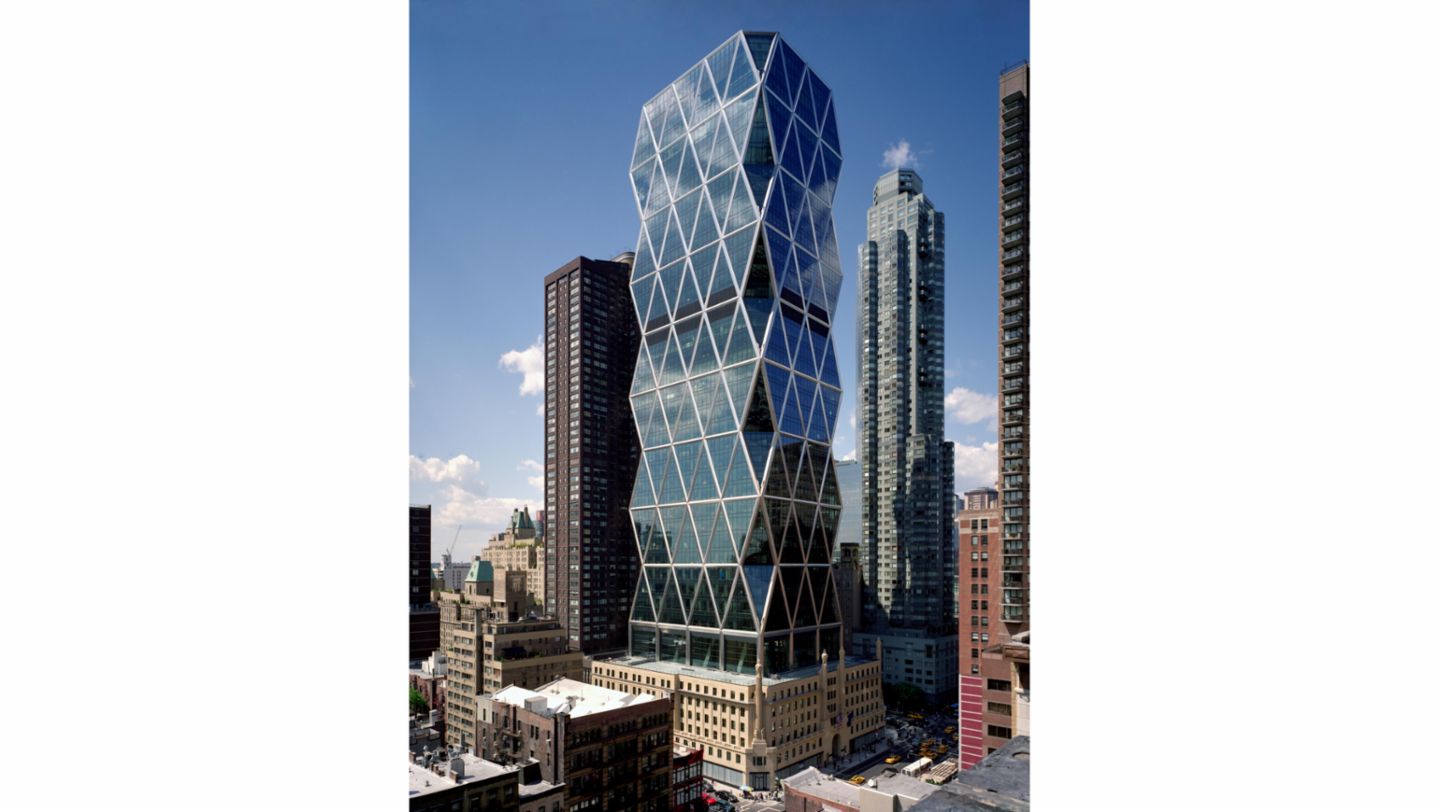

With the help of new computer technology, Foster’s ideas morph even more intensively into his constructions. The smoky black glass front of the Willis Faber & Dumas building in Ipswich, England, causes a stir in the early 1970s. So too does the 44-story HSBC office tower in Hong Kong in 1986. Foster attracts worldwide attention by turning the entire building structure inside out. His first airport, London Stansted, follows in 1991. Along with Beijing Capital International Airport, Foster illuminates the inside of an airport terminal for the first time with natural light. His creativity seems both limitless and weightless.

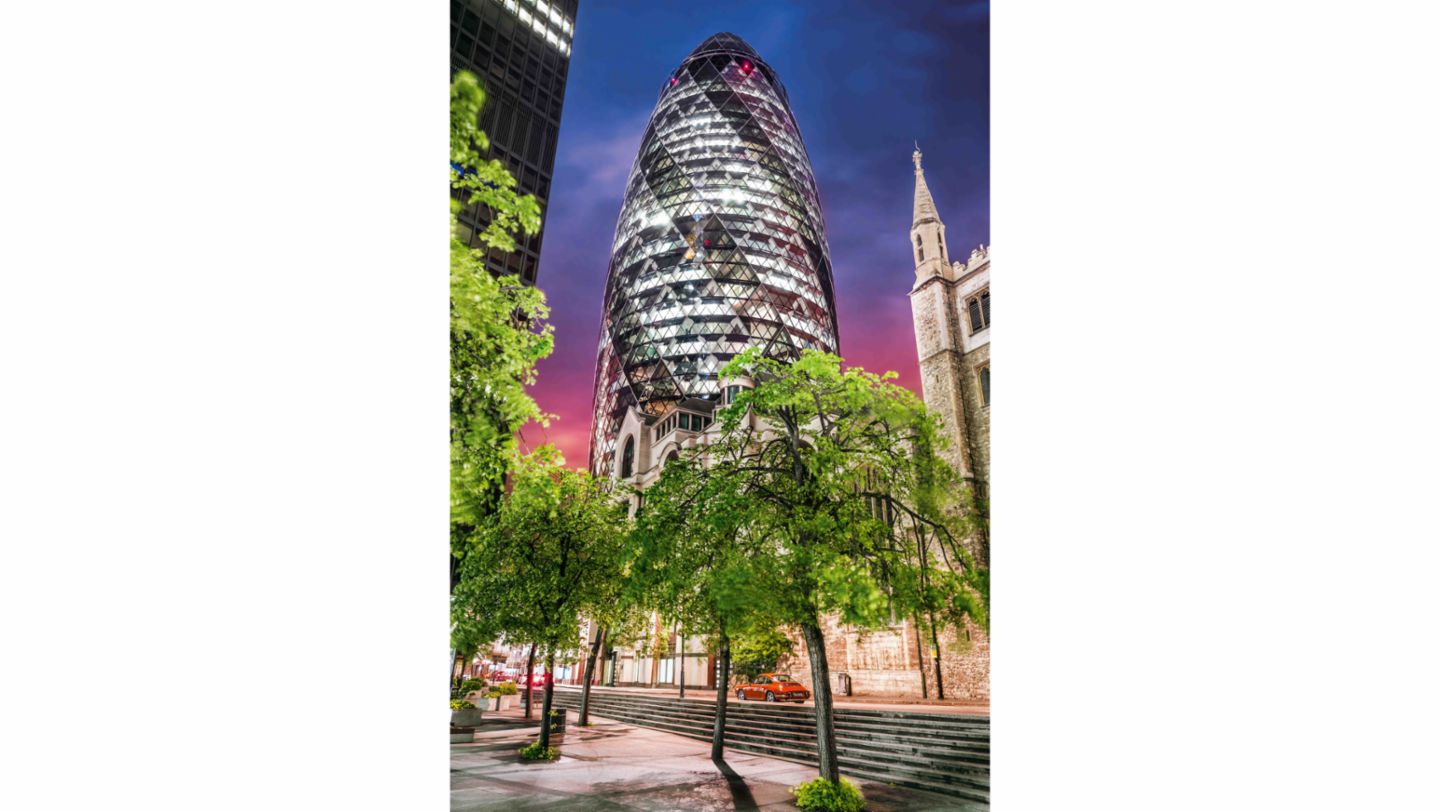

His architecture conquers the globe, winning an ever lengthening list of prizes and awards. Queen Elizabeth II confers a knighthood upon him in 1990. The Millennium Bridge, the high-rise dubbed the Gherkin, and Wembley Stadium form the modern face of London. In 1999, the queen makes him a life peer – he now has the title Lord Foster of Thames Bank and a seat in the House of Lords, the upper house of Parliament in the United Kingdom. “A solemn and humbling occasion” is how Foster describes the ceremony. “But far more important was the profound recognition of architecture for society.”

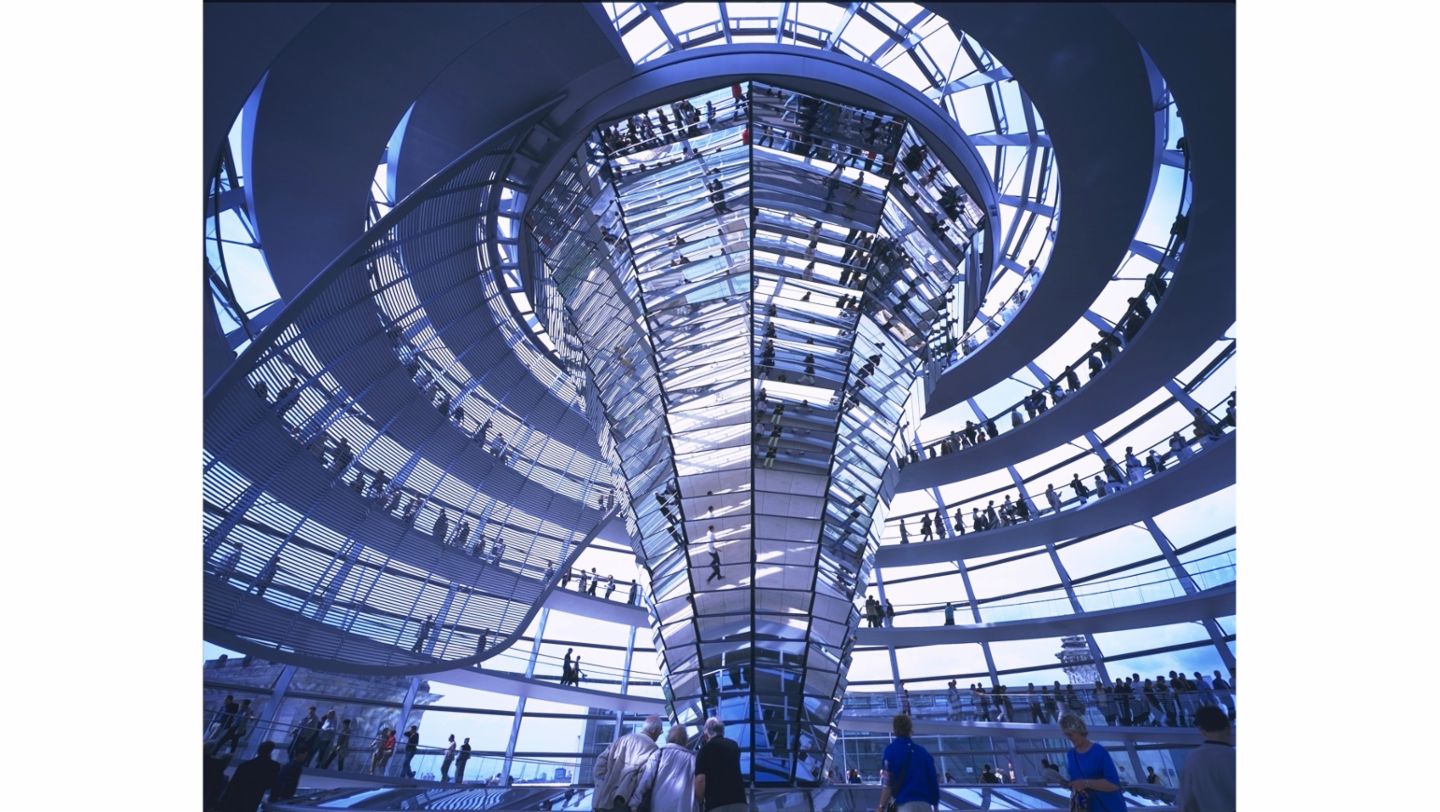

That same year he receives the globally renowned Pritzker Architecture Prize – in Berlin, where he wins the contract for restructuring the German Reichstag building. “This might be my most meaningful project,” he observes. Foster takes a holistic approach to everything from the arrangement of the rows of seats to the design of a monumental eagle and the lines of the glass dome. “We modeled the dome at a scale of 1:20, lifted it with a crane onto the real Reichstag building, and went inside. We wanted to see how the interior would affect us.” The greatest degree of sensitivity is required in light of the political repercussions of architectural decisions. “Helmut Kohl was chancellor at the time, and I remember how he walked through the site with me and expressed his desire for certain colors – he definitely wanted something uplifting for a unified Germany.” Foster also convinces the chancellor to preserve the Cyrillic inscriptions left on the walls by Red Army soldiers in 1945.

For the design of the two-and-half-ton eagle that peers down onto the parliamentarians, Foster travels to Japan and spends days in the mountains studying wild birds of prey. But still, “the federal eagle is a compromise – I would have preferred a somewhat leaner look.”

Act six – Apple Park

“Hey Norman, this is Steve, I need your help.” This call resulted in what may well be the most spectacular office complex in the world – Apple Park. The computer company’s headquarters are located in Silicon Valley in the town of Cupertino, where founder Steve Jobs grew up. “That was a really special type of collaboration,” says Foster. “Steve didn’t want me to see him as a client but rather as a member of my team. He told me how in his youth, Silicon Valley produced most of the fruit for America. This was the inspiration for Apple Park.”

Apple Park is considered one of the most progressive examples of corporate architecture. It is powered entirely by renewable energy. Solar installations on the campus generate up to 17 megawatts and form one of the world’s largest rooftop solar power systems.

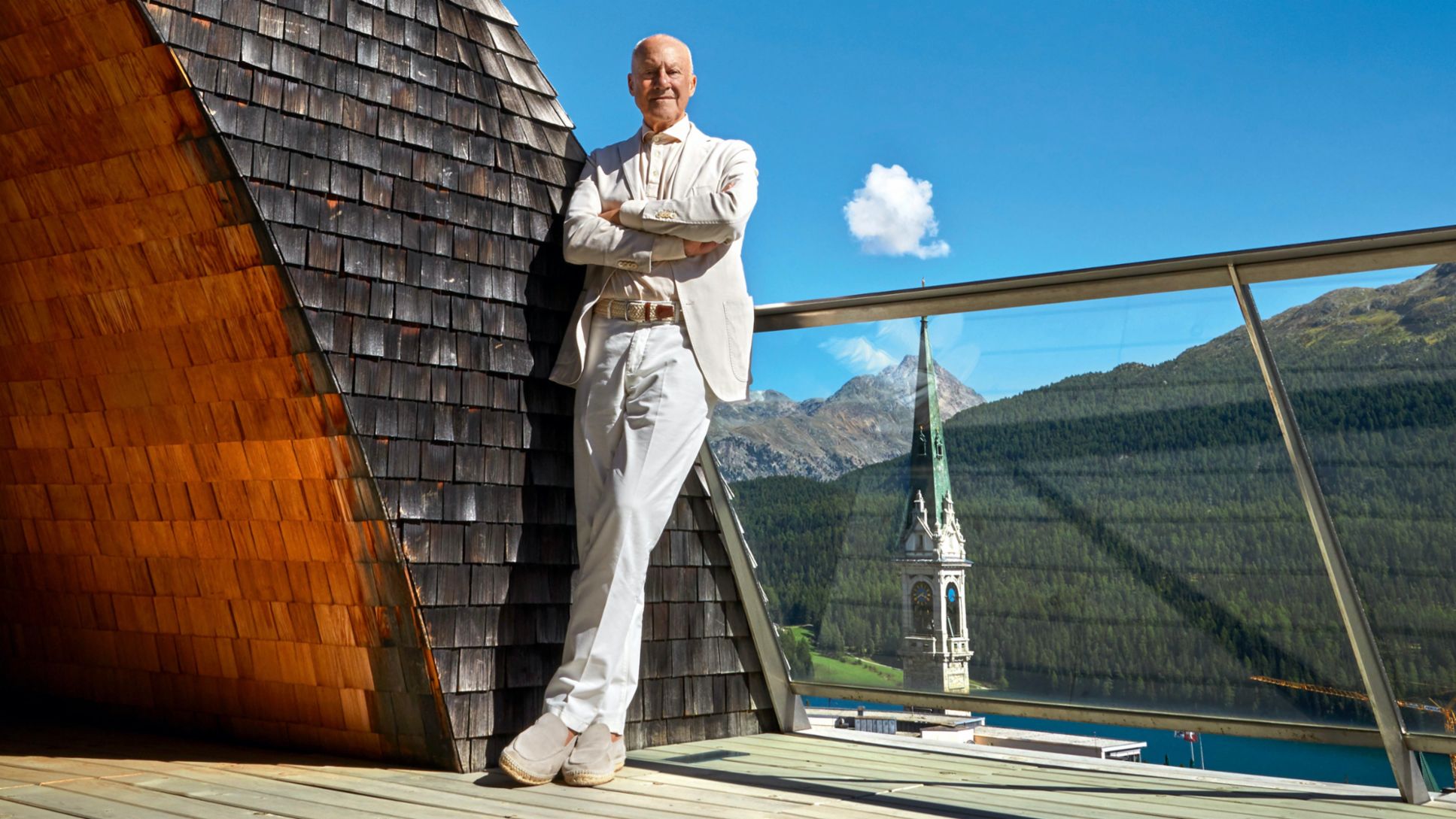

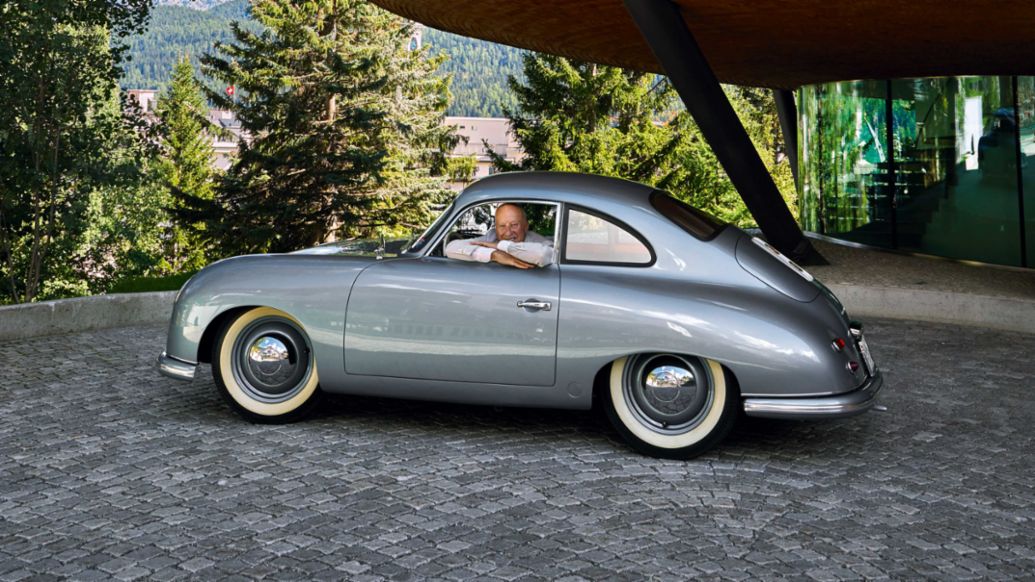

Act seven – Chesa Futura and the 356

Some 250,000 hand-cut larch shingles make up the façade of this building. Viewed from the opposite side of the lake, it blends into the hues of the Swiss mountain landscape. Chesa futura means “house of the future” in Romansch, the original language of the canton of Grisons. Foster places his private residential complex in the middle of the Swiss ski resort of St. Moritz – where it resembles a spaceship on earth. “Chesa Futura is very alive,” says its creator, “just like my Porsche here.” Foster’s Fish Silver Grey 356 has a split window, which marks it as an early model from the Stuttgart production. “The way the car reflects Chesa’s form and vice versa – isn’t that wonderful?” He loves driving on the winding roads and over the mountain passes of his adopted home. Yet the odometer shows only around 6,000 kilometres. “That will probably change now that my youngest son has his driver’s license,” says Foster with a smile, and proceeds to recount the early history of his 356.

“It was delivered to a buyer in Hamburg in October of 1950. In 1955, it was bought by RAF squadron leader Robert ‘Porky’ Munro, who imported it to Great Britain and registered it with a license plate reading UXB 12 for ‘unexploded bomb’. In 1957, Munro became the head test pilot for the Hawker-Siddeley Kestrel, the prototype for the Harrier Jump Jet – one of my favourite designs.” With a ski rack on its roof, Foster’s black 356 C Cabriolet stands ready for the impromptu cross-country ski excursions that Foster loves. “The glamour that people associate with the 356 these days belies its roots,” he notes in a philosophical tone of voice. “It was developed at a time of scarcity and made of the parts available in the post-war years.”

Lord Norman Foster, who counted his pence as a child in order to reach for the skies in his dreams with comic-book hero Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future, and whose architectural daring then made him a real life “pilot of the future”, is thankful. “I value these sports cars very much, like I do my life. It is a privilege to still be able to enjoy every drive.”

Info

Text first published in the Porsche magazine Christophorus, No. 398.