If this was a normal year, Jürgen Barth would be looking forward to a Le Mans catch up with his old racing pals at the Rolex dinner at the Mulsanne golf course. It’s safe to assume it wouldn’t be a quiet evening – with 14 appearances at the 24-hour race, driving everything from a privateer 911 to the legendary 956, Barth has plenty of tales and a whole host of racing mates.

Had he not retired as a Porsche factory driver last year, Jörg Bergmeister’s pre-match routine would have been very different. With a total of 17 GT-class Le Mans appearances since 2002, Bergmeister has been at the sharp end of Le Mans more recently than Barth. That would mean fewer gastronomic delights for Bergmeister, and more “have I remembered my helmet and overalls?” mental notes.

But 2020 is not a normal year. The coronavirus has shattered sporting fixtures all over the world and Le Mans is no different. The crisis has laid waste to any plans that Barth or Bergmeister had of attending the race, as all spectators are banned and support team numbers have been stripped to the bare minimum. As a result, both will be watching from afar.

As the countdown to the endurance race of the year begins, the two men – both equally famous for their privateer efforts as their factory successes – swop stories on the life of a non-works outfit.

Jürgen Barth: “I remember the first time I came to Le Mans was something like 1968, after I finished my apprenticeship. I came in a white shirt and within one hour of the start of the race, it was filthy as I was helping customers with their cars. One customer was in a 910 and I had to weld their exhaust just before the start!”

Jörg Bergmeister: “That’s so cool. To be honest, when I first went in 2002, I was a bit “yeah, it’s a 24 hour race like all the others”. But how wrong I was. That first experience – the drivers’ parade, seeing all the emotion on the faces of the people watching, and then during the race going through the Porsche Curves with all the flashing lights … it quickly became my favourite event and I’m so happy that I got to be part of some of the races there. It’s definitely a special place.

My fondest memory is from 2004, and my first class win. I’d had a bike crash the week before the race and didn’t even know if I would make it because I was in so much pain from the road rash all over my body. But we still got the victory with Patrick Long and Sascha Maassen.”

Barth: “To me, there are two big circuits to win at: Indianapolis and Le Mans. When you win Le Mans, there are 220,000 spectators and it’s incredibly emotional. When I won in 1977, I didn’t fully realise until afterwards that I had won Le Mans – and then the emotions hit.

It felt different back then, because we had to think that at nearly every race, including Le Mans, we could lose one of the drivers in a crash. A lot of guys got killed. Winning was an emotional release. Ooof, we finished the qualifying. Ooof, we finished the race. We had some big, big parties – even after qualifying. We practically flooded the restaurant with champagne.”

Bergmeister: “For sure, the consequences were very different for you back then. Unfortunately, I also had an awful experience when we lost Allan Simonsen in 2013. It was very sad. But over time the track got better, the cars are a lot safer and luckily there aren’t that many losses any more.”

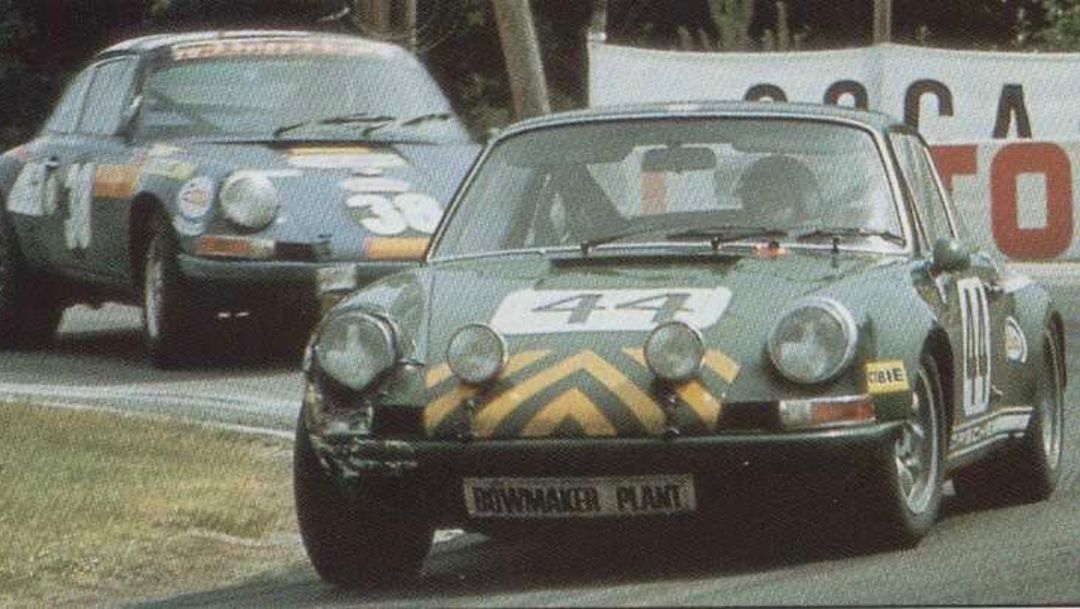

Barth: “Exactly. And today, race cars are more like road cars. But in our time, we didn’t have servo brakes, servo steering, there wasn’t any paddle shift. Plus we were only running two drivers. Sometimes nowadays, at places like Daytona, there are five or six drivers. The first race I did in 1971 was with René Mazzia in a 911.

I didn’t speak much French and after scrutineering I heard a little “tick, tick, tick” noise from the engine. I found the piston was hitting the cylinder head. I didn’t have any spacers or anything so I took a file and took off a little bit of the pistons.”

Bergmeister: “That’s amazing.”

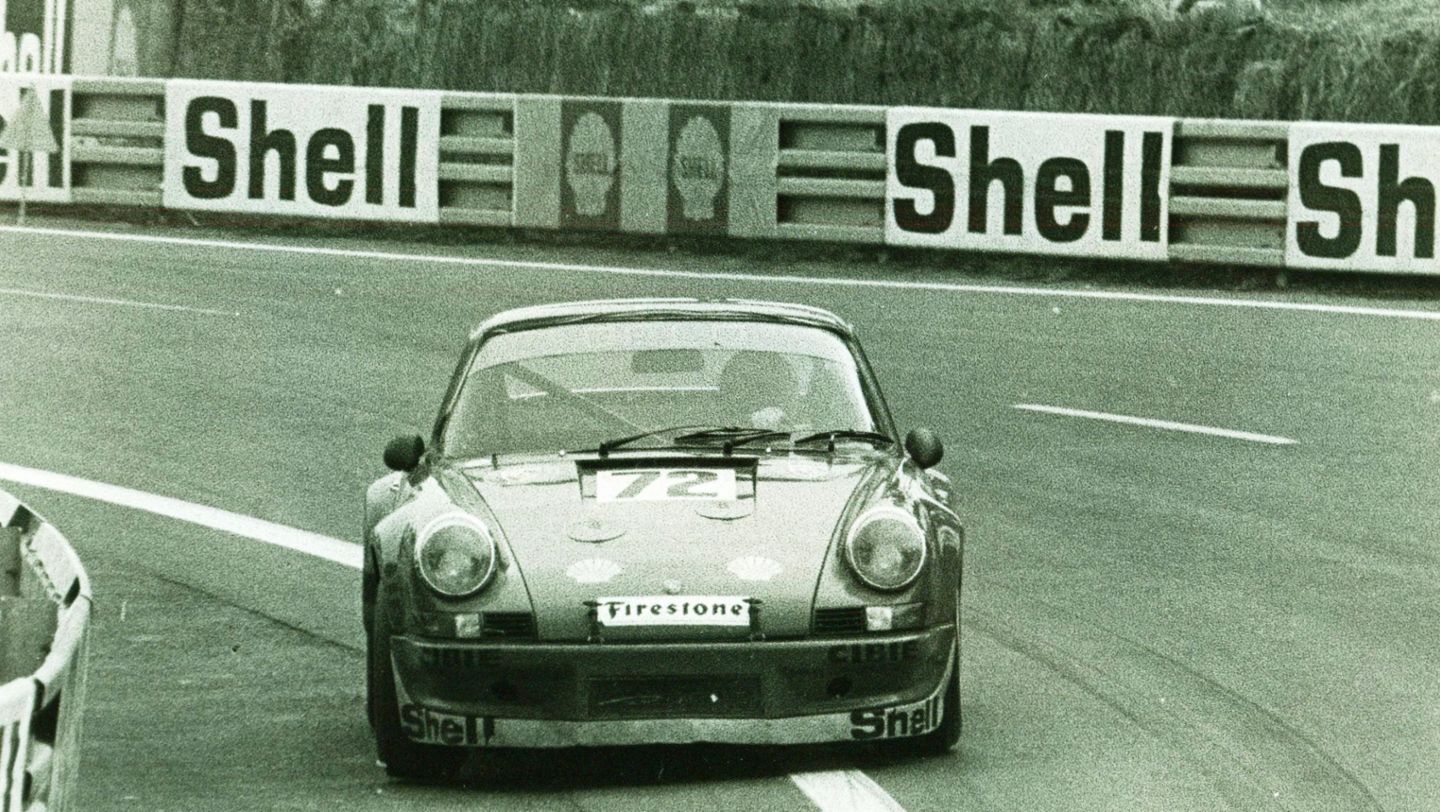

Barth: “Also, today, I feel it’s turned into much more of a sprint race because of the materials in the car. They’re getting better, better, better. You go flat out for longer. At the time when I was winning, we had to be careful to cool the engine by lifting twice on the straight. 10 years later, we had the first fuel injection with the 962 and it was full-hard, flat-out.”

Bergmeister: “Same for me. Even at the beginning, with the 996, you had to be careful to look after your equipment.

But ever since we had the 991, even the really hard kerbs, the hard baguettes, you just hit them like in a sprint race. It feels quite cruel but the cars take it. It’s the only way to go quick nowadays. Everybody does it so it means the equipment has to last.”

Barth: “We had to be careful with kerbs. With the 911 it wasn’t so bad because the suspension was no problem. What you had to be careful of in the 911 was not over-revving the engine, and you had to watch the fuel and the tyres, but suspension-wise, the car would cope with the kerbs.

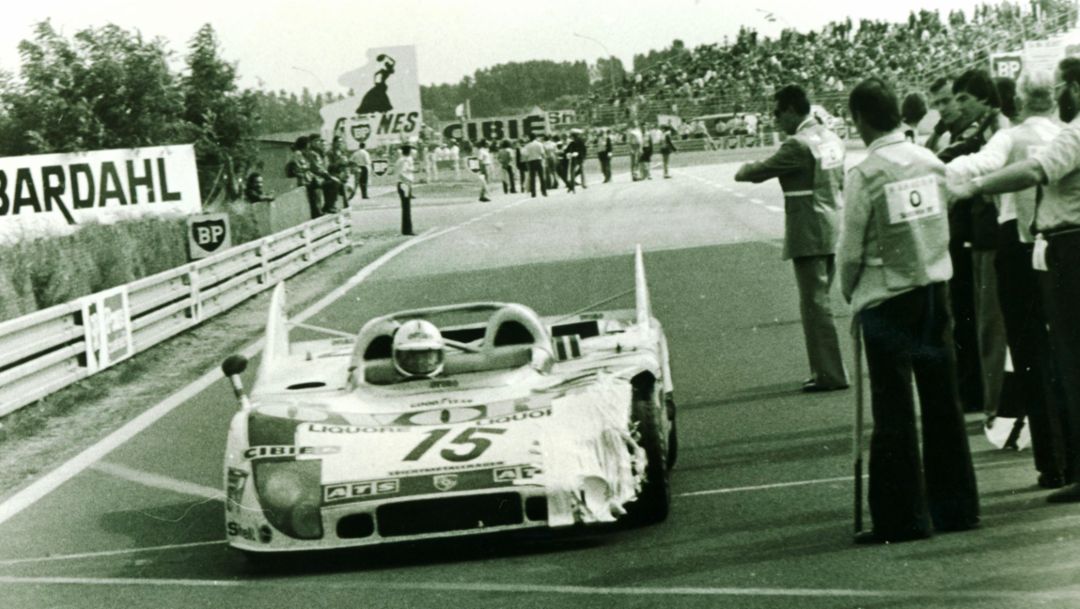

With the prototype, the 908, we had to be really careful not to hit any kerbs. The wheel hubs were quite fragile. Later, in the 962, you could hit the kerbs and nothing would happen. But in that car, you had to be careful with the aerodynamics because you had ground effect cars. You had to avoid having too much turbulence in front of you and not to follow the car in front too closely.

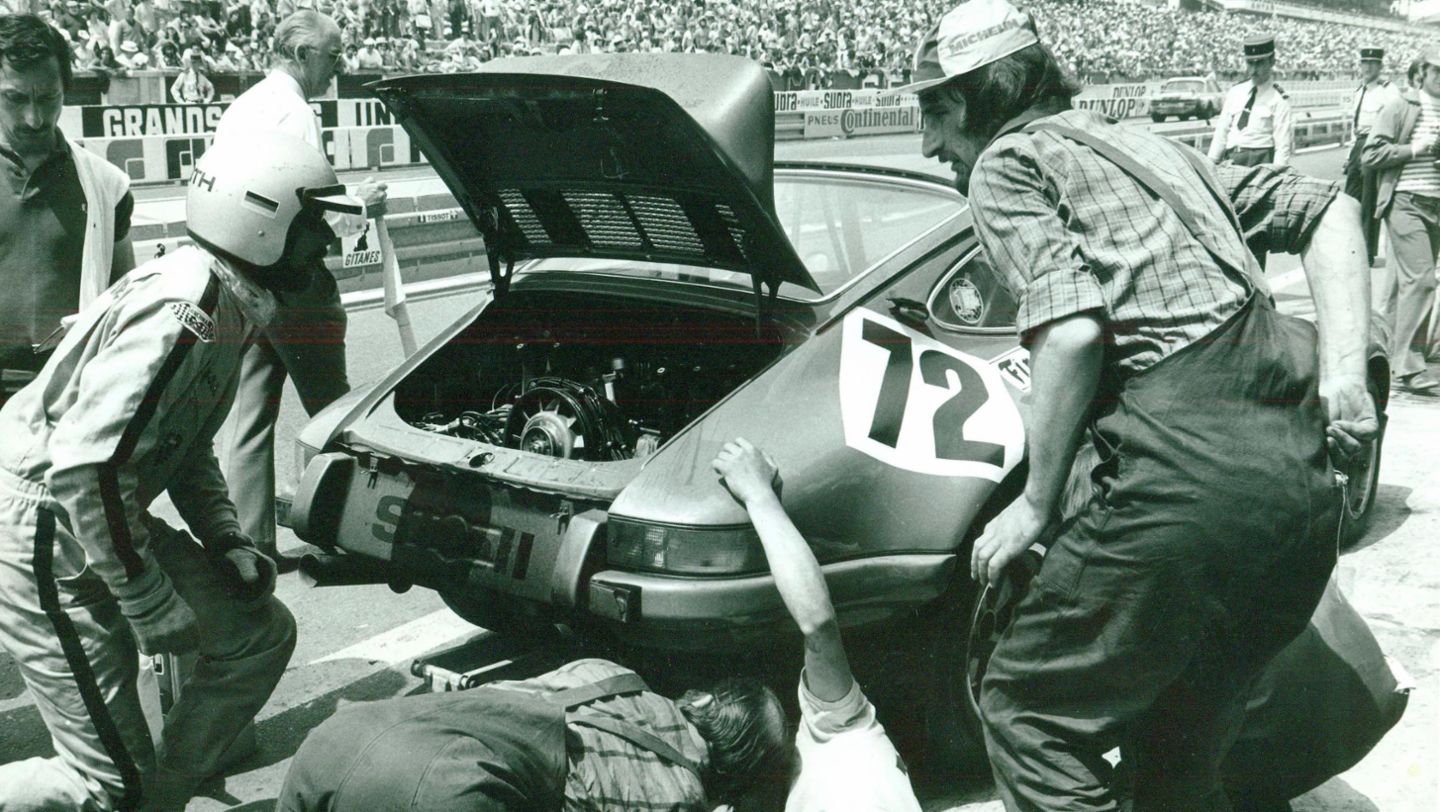

Of course, when you’re racing for the privateers, you had to look after the cars – privateer budgets were different. From the 1970s to the 90s, we were trying to build cars that were reasonably priced for customers because we needed customers to fill up the field. That was always good for Porsche because we had a lot of cars in the field and we always had a chance of winning the class.”

Bergmeister: “For me, the biggest difference between a privateer and a factory effort, especially in GT, is just the level of preparation. With Flying Lizard, we were already on a very good level because it was a factory supported team, but if I compare it now with the factory GT team, it’s a whole different world. You have an engine guy every time you fire up the car. You have a data guy, a car engineer. The attention to detail and the preparation has definitely changed a lot in the last 15 years. At least for me, at the beginning, you sat in the car and had data recording but that was pretty much it. Nowadays, even while driving, the data is analysed, even down to downforce level and whether something has changed on the splitter. That level is completely different. Now, there are probably around 100 people going to the race.”

Barth: “More, more for the prototypes.”

Bergmeister: “I liked it a bit simpler because you could give more input. For me, I enjoyed not just being a driver but also trying to organise things in the background: getting the best out of the team and really making sure things were done in the right way.

The last effort with Project 1 was quite a big challenge to bring them up from a Supercup team to endurance racing in one season. Luckily I had some really good people who ran F2 before, or GT2, but it’s a different challenge to build a team then get everyone in the right mindset.”

Barth: “Same for me. Since I had a mechanic’s background, I was used to helping out however I could, to recover the car or similar. Like in my last two laps of Le Mans when I had to run with one fewer cylinders. But at the time, this was normal, at least for me, because I was also working in the factory, being a driver and also looking after the customers. So I was multi-tasking. The mechanic would come and ask for a soup, and I had to find him one.”

Bergmeister: “Yes. Why not, right? We’re one team, after all. I slept in the trailer for the last two years so that camaraderie was still there.

I’ll definitely miss it but I’m looking forward to watching the race. It doesn’t what time of the year it is, Le Mans is always a cool track. To me, it doesn’t matter if it’s December or June, if you have a chance to race there, you always say yes.”

Barth: “Definitely.”

Info

In part two, former works driver Timo Bernhard talks to engineering legend Norbert Singer. The article will be published tomorrow on newsroom.porsche.com.