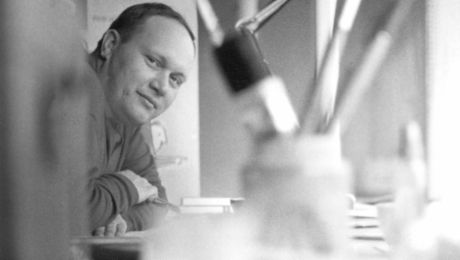

There’s a sense that Neo Rauch might have turned himself into a work of art. The way he climbs with a certain angular elegance out of his blue Porsche 911. The way he shakes hands with journalists, colleagues, and friends, with a precisely dispensed degree of formality or warmth. On this summer morning, he has driven from Leipzig to Aschersleben in the state of Saxony-Anhalt to open an exhibition entitled The Knitter at the Neo Rauch Foundation of Graphic Works. The exhibition is Rauch’s present to his wife, Rosa Loy, for her sixtieth birthday. He’s wearing a black polo shirt, jeans, and silver cowboy boots. “Of course I’m vain,” he says. “I hope everyone is. Those who aren’t are a scourge.”

Rauch is one of the most important artists of his generation

It might seem superficial to focus on Rauch’s external appearance. After all, he’s considered one of the most important artists of his generation. He’s something of a figurehead for the New Leipzig School and one of only a few living artists to be honored during their lifetime by an exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. His works sell for seven-figure sums. On the other hand, the fifty-eight-year-old resident of Leipzig is passionate about beauty. He’s enraptured with the buildings and alleyways of Aschersleben, the oldest city in Saxony-Anhalt and his hometown, and with the gentle hills that surround it. A little of this rhapsodic quality is reflected in his art. The prints and sketches shown in Aschersleben are immediately recognizable as works by Rauch.

The dark landscapes populated by soldiers, laborers, and mysterious hybrid beings evoke worlds that could appear in a dream, or a nightmare. Uncanny and enchanted—but the enchantment is precisely what gives them their enigmatic beauty. He’s not aiming to create beauty when he approaches the canvas, he says. But he’s pleased when his finished works are considered as such. “Beauty never fails to touch something within us, to render us speechless and give us pause. That applies to works of art, to landscapes, to individuals, and maybe also to objects of everyday use.”

Language reflects attitude

Rauch’s foundation is located in an architecturally appealing annex of a former paper factory; the exhibition space is located on the second floor. One story below, on the same level as the parking lot—down-to-earth, so to speak—stands a 911. When talking about his sports car, Rauch doesn’t spout facts and figures like a fan besotted with statistics, instead beholding the vehicle as an artist. “It has a form I wouldn’t change in the slightest. The designers managed to resist the temptation to distort its face into the features of a fighter. So many other cars look like they’re ready to brawl, to smack their opponents off the roads with chest-pounding postures,

When Rauch speaks, he often doesn’t look at the other person’s face, but rather upward to the side, as if the well-crafted sentences that emerge from his mouth were written somewhere on the wall. He’s not only a man of colors and shapes but also of words. He reads extensively and admires authors like Ernst Jünger. And he composes his sentences as carefully as his paintings. “It’s important to have aspiring and beautiful forms of speech. We neglect this at our peril.” Rauch’s language is an act of courtesy and, one might say, a type of attitude. “I too harbor a tendency toward negligence. But at least I’m still aware of it, examine myself on occasion, and call myself to account. In general, however, I’d have to say that manners have sunk to a disheartening level.”

Rauch likes to bring up his teacher in connection with this topic. Arno Rink was a member of the Leipzig School who required his students to stand when he entered the room. Yet he could hold his own with the wildest attendees at the art academy’s legendary parties. Good manners also mean not always being fixated on oneself and one’s own sensibilities, but being able to forget them on occasion. Even if only for a few minutes.

Snug in a 911

His Porsche also serves as an escape from everyday life, he says. He bought it to console himself after his son moved out. On weekdays, he usually rides a bicycle. The car isn’t an object of utility for him, but rather of pleasure. “When I’m encased in the Porsche, I feel good in every respect. It surrounds you as a driver, without impeding you.” Cars from other makers are becoming ever larger, with an ever more bloated appearance. “But here, it’s still immediately evident how closely driver and vehicle are connected. The car is a direct extension of the driver’s will.” Behind the wheel he feels his own agency and a type of freedom. “I’m absolutely autonomous in the car. Even in a traffic jam I feel more at home than I would in a train compartment with people I don’t know who subject me to their taste in music.”

It’s not terribly reasonable to own a Porsche, he says. But it’s a type of unreasonableness he wouldn’t want to do without. “You can drink nonalcoholic beer, eat vegan, not wear leather shoes, or drive cars. You can do all of that, but why? A life without irrationality, without excess, is a gift not used.”

To truth beauty goodness

Rauch has resisted excessively reasonable, rational, and moralizing approaches as an artist as well. He wants his work to remain a mystery. As he leads us through the exhibition, a woman remarks that she hopes Rauch will explain a few of his works. Rauch, the man of courtesy and well-chosen words, smiles gently, looks up to the side again, and responds, “Explanation was never the intent. It has more to do with transfiguration.” And that appears to be how Neo Rauch views not only art but also life, everyday routines, and maybe also a car. For him it’s about enchantment. “It’s important to marvel,” he says. “Marveling has an element of something like reverence. People who wonder might be a little naive. But anyone can marvel, even the sharpest individuals. The urge to marvel is something we definitely need to retain.”

The exhibition "The Knitter"

Neo Rauch founded the Neo Rauch Foundation of Graphic Works in Aschersleben in 2012. The foundation has since received one of each of Rauch’s prints and put on annual exhibitions. The Knitter is the current show, which will run until April 28, 2019. It has a special status: it juxtaposes works by Rauch with those of Rosa Loy, with whom Rauch has lived and worked for more than thirty years. On view are around 140 prints and drawings as well as large-format paintings by the two artists. Common and contrasting features of their respective approaches become evident. Both paint figurative works, create fantastical worlds, and highlight tensions between art and the real world. But whereas Rauch’s content is generally dark and dramatic, Loy’s work, which often depicts female figures, is more delicate. The couple chose the exhibition title as a metaphor—because knitting is about following a thread, making connections, bringing different strands together. As an aside, Loy also enjoys knitting. “When we play chess, she sits there and knits,” says Rauch. “It’s humiliating. I’ve never managed to win a game against her.”

Info

Text first published in the Porsche customer magazine Christophorus, No. 388