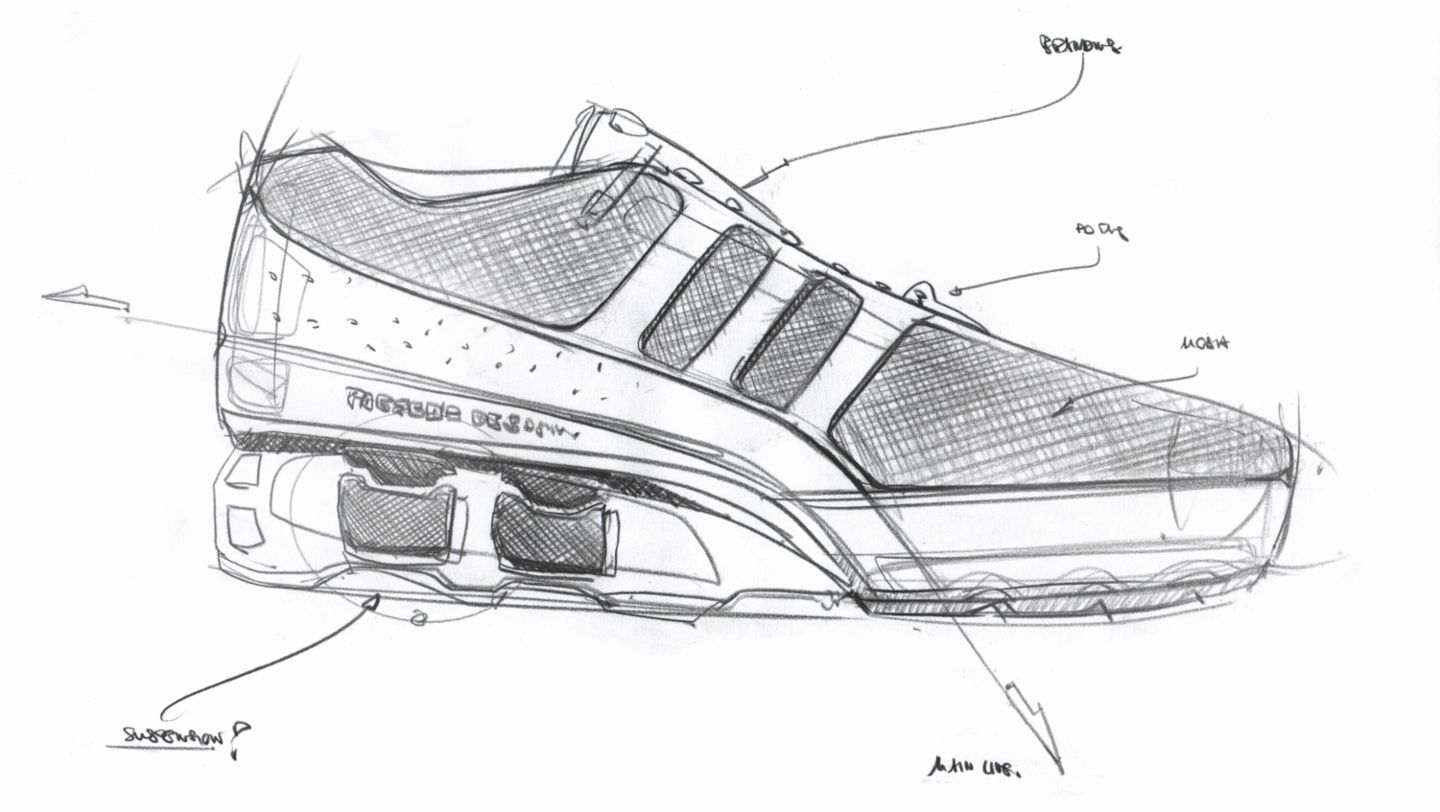

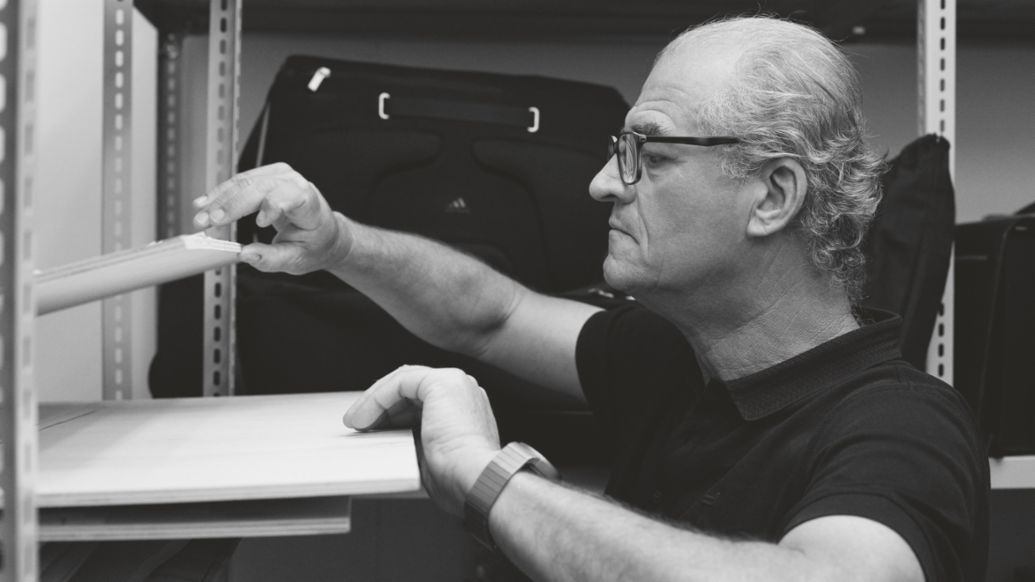

It’s a scenario that authors, artists, architects, and of course designers will be familiar with: staring at a blank sheet of paper wondering how to begin, what words and ideas to use, and generally how to create a new world from scratch. There are countless tales by authors of how agonizing the start is, when you are trying to find your way into the text. Designers know how this feels, too: a blank page looking up at them accusingly, the silent battle they wage with it: “It’s time for you to draw something groundbreaking on me!” Ideas then take shape as black lines. The sketch is discarded, redrawn, refined. The long journey to the finished product, the gradual materialization of an idea in titanium, stainless steel, or aluminum, begins here at the drawing board. Designers have to tackle a whole range of challenges. The ones at Porsche Design are particularly big: “Our designs should break new creative ground, rethink an existing principle, be exceptionally functional, and of course technologically feasible without difficulty,” says Christian Schwamkrug, Design Director at Studio F. A. Porsche.

These requirements were written into the company’s DNA from the outset. Professor Ferdinand Alexander Porsche’s design of the Chronograph I, for example, fulfilled them all. With its black finish, the watch looked completely different to traditional models of its time. It was radically functional, starting with the unique design of the face, from which you can clearly read the time even in poor lighting and extreme situations. In the same way as an author lends us a new perspective on reality with a story, a designer does this with a welldesigned product.

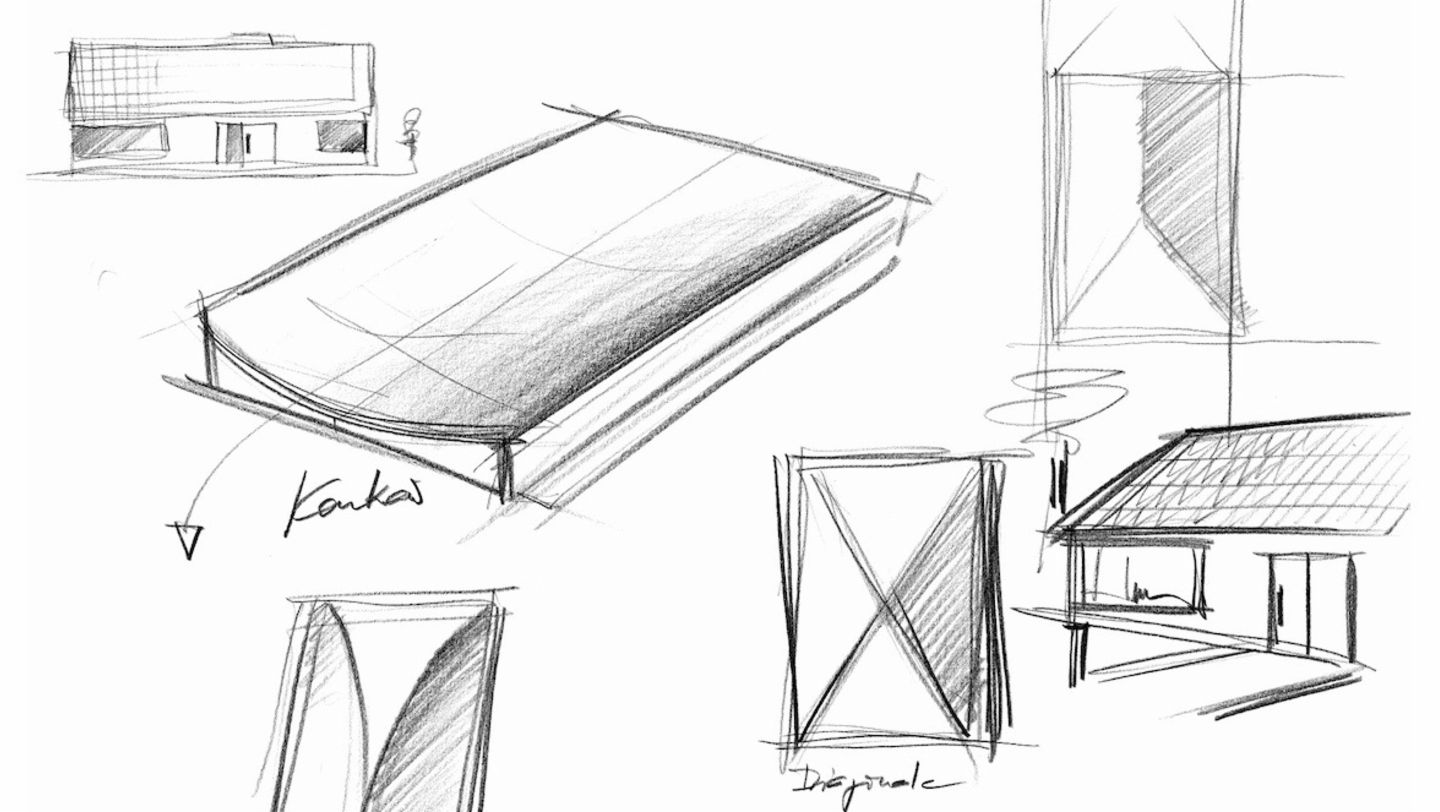

It gives us pleasure through its serene beauty and finds a different way to make our everyday lives easier thanks to its obvious functionality. Ideally, it does not show the complex work that went into it, but you can be sure that enormous passion and dedication were required. “Above all, it’s not easy to gain something new from an object whose principle is actually already very well conceived,” says Schwamkrug. For example, Studio F. A. Porsche was asked not so long ago to design a roof tile – an object with an almost archetypal shape that any child can draw. What is more, the fixed aspects such as the material clay, the standardized dimensions, and the production process put tight constraints on any design. “Where do you even start? What innovation can we come up with that meets our expectations and those of the customer? We were extremely skeptical to begin with.”

But it is precisely these moments that separate the truly creative designers from the rest. In the studio, the team thought about the function and shape of roof tiles, about how they could improve the drainage of water when it rains, or how the tiles reflect sunlight. “An intense, creative energy was released,” recalls Schwamkrug. The result was eleven designs that consider the roof tile primarily as an architectural element, enable a unique interplay of light (depending on the incidence of light), and give any house a new appearance. From such in itial ideas, Design Director Schwamkrug normally selects four to five concepts that are then visualized using 3D programs and ultimately rendered so that they already appear very lifelike and can be presented to the customer. “In the case of the roof tiles, it didn’t take long to find our favorite. It had a distinct Vshape, the drainage of water was optimized, and light reflection was integrated as a design effect,” says Schwamkrug. The customer made a very quick decision, and only twelve months after the first sketch, the V11 roof tile went into series production. “And it’s been very successful on the market!”, says Schwamkrug.

But not everything is as straight forward as this. Like authors or artists, designers are also familiar with creative blocks, when every design is feeble, and no progress is being made. “When that happens, all you can do is take a step back, think about something else for a while, and–most importantly of all – talk to your colleagues,” says Schwamkrug.

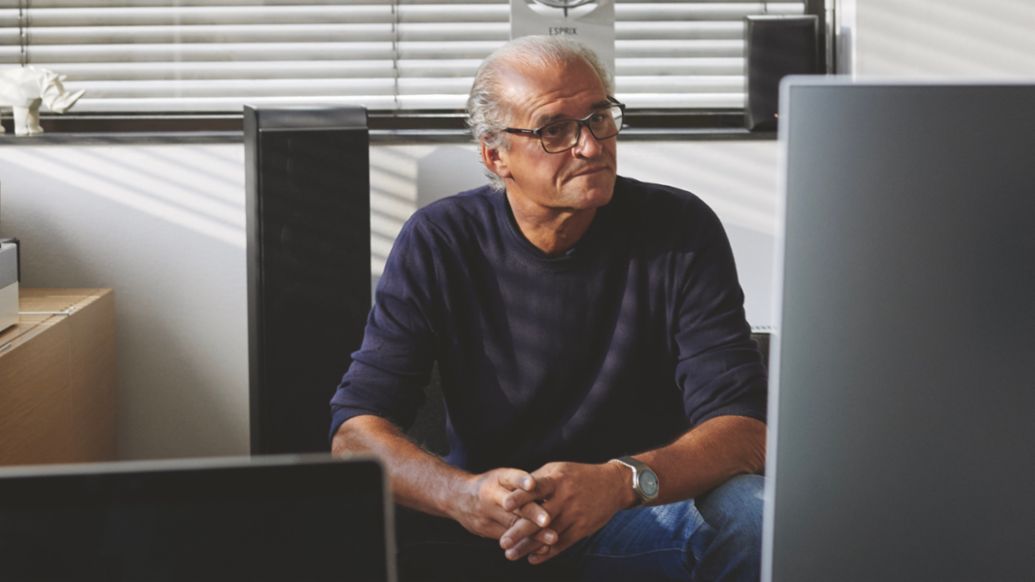

“It's not easy to gain something new from an object whose principle is actually already very well conceived.” Christian Schwamkrug

A culture of exchange is practiced at Studio F. A. Porsche. A variety of perspectives on a subject, along with debates and discussions, are required until a balanced and incomparable design emerges from the different basic ideas. Another challenge is the wide range of possibilities offered by today’s design software, which significantly accelerates the design process because it allows a hand drawing to be swiftly rendered in a manner that appears highly tangible and workable. “There is a risk that you as a designer are satisfied too quickly because the virtual model already looks almost perfect. But it’s the details that matter – and it’s easy to overlook them,” says Schwamkrug. That is why he and his team hold many discus sions to examine why each individual decision was taken.

“If the argument made by a designer for a particular design de cision isn’t plausible and convincing, they have to come up with a better one,” says Schwamkrug. “On the other hand, I also have to accept points of view if they are backed up by logic, even if I don’t necessarily agree with them.” This is how the studio gradually approaches its goal. A project undergoes approximately six to eight internal rounds of discussion before it is presented to the customer or the production partner. Another crucial factor is that a design not only has to be innovative and attractive, it must be feasible without requiring enormous expense and effort. The designers contact the engineers at the manufacturer early on to ensure that they are not including something in the product that is not realizable from a constructive point of view.

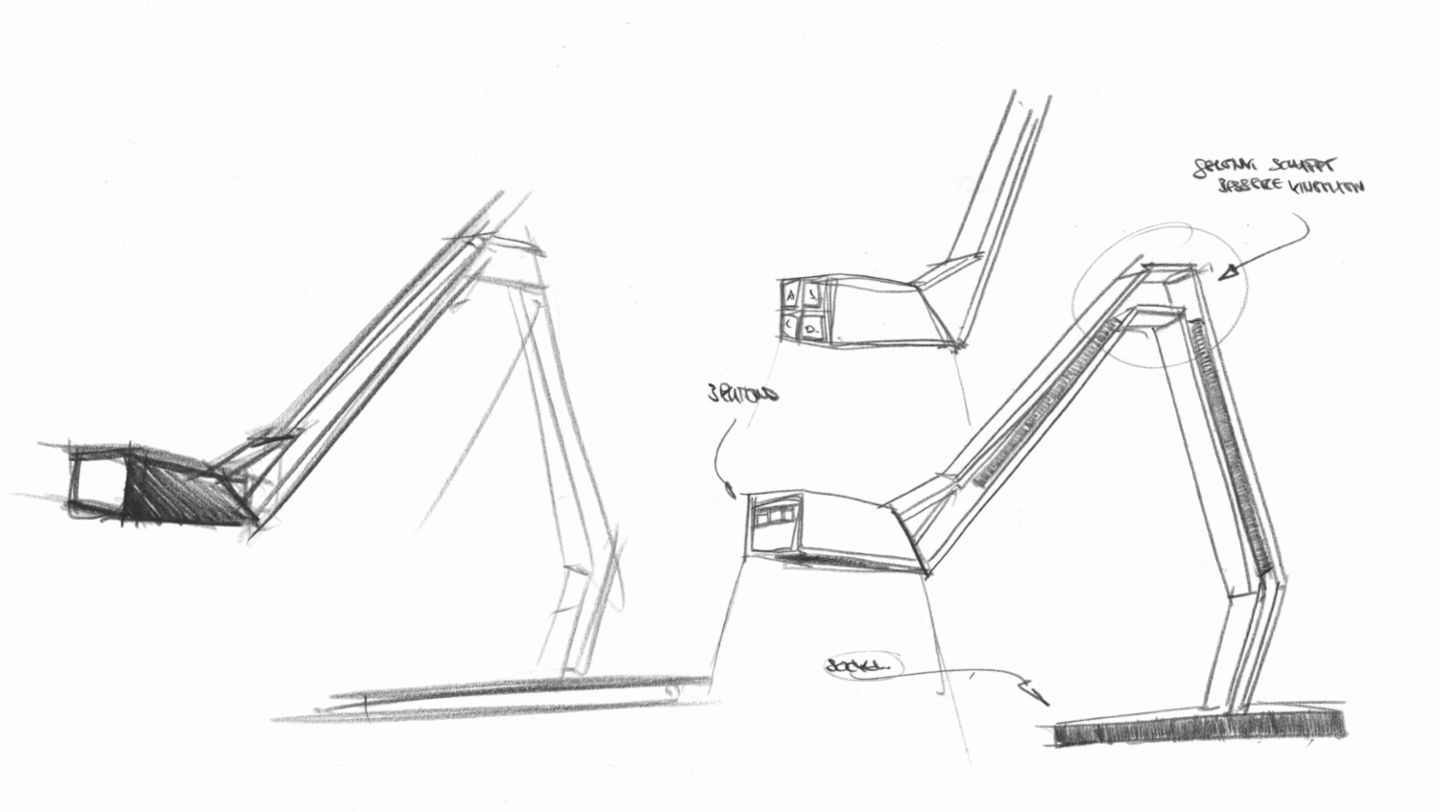

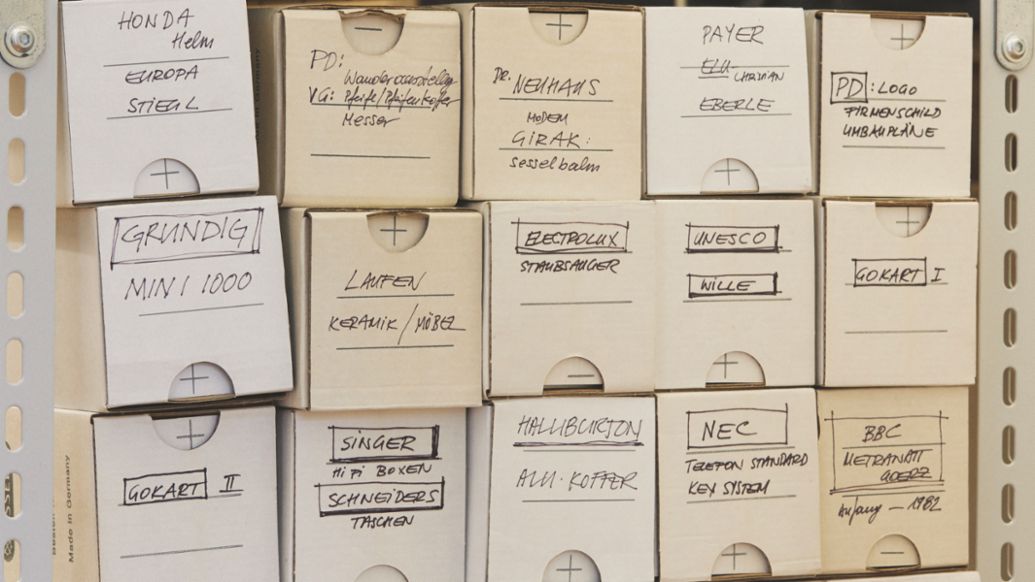

This balanced and precise approach allows Studio F. A. Porsche to take on complex projects, such as for a series of dentist’s chairs for the Japanese company Morita, which placed specific require ments on the team in terms or ergonomics and application. Each chair had to be adaptable to the needs of the respective dentist, be modular and, despite series production, individually configurable. “A difficult task, but one we mastered extremely well,” says Schwamkrug. The Signo T500 dental unit range won the Red Dot Best of the Best Design Award in 2019. This is just one of the more than 250 awards that Studio F. A. Porsche has won in its history. The dentist’s chair project fits seamlessly into the success ful heritage of Porsche Design, which is full of products that have become classics.

These naturally include the Chronograph I, the P’8478 Sunglasses with in terchangeable lenses, and the LaserFlex Ballpoint Pen, which almost perfectly reflects F. A. Porsche’s philosophy: “When you consider the function of a product, sometimes the form follows automatically.” The shaft of the pen is made of stain less steel, but is nevertheless flexible be cause it has been divided into fine rings using laser technology. The fine meander structure of the rings means that they are not detachable from each other. Between the rings there are joints that, if added together, show exactly how to reveal the ballpoint or slide it back into the shaft. When the shaft is pressed, the whole pen is compressed and the ballpoint pops out. Initially concentrating on the function of a ballpoint pen led to a form that is unusual and innovative.

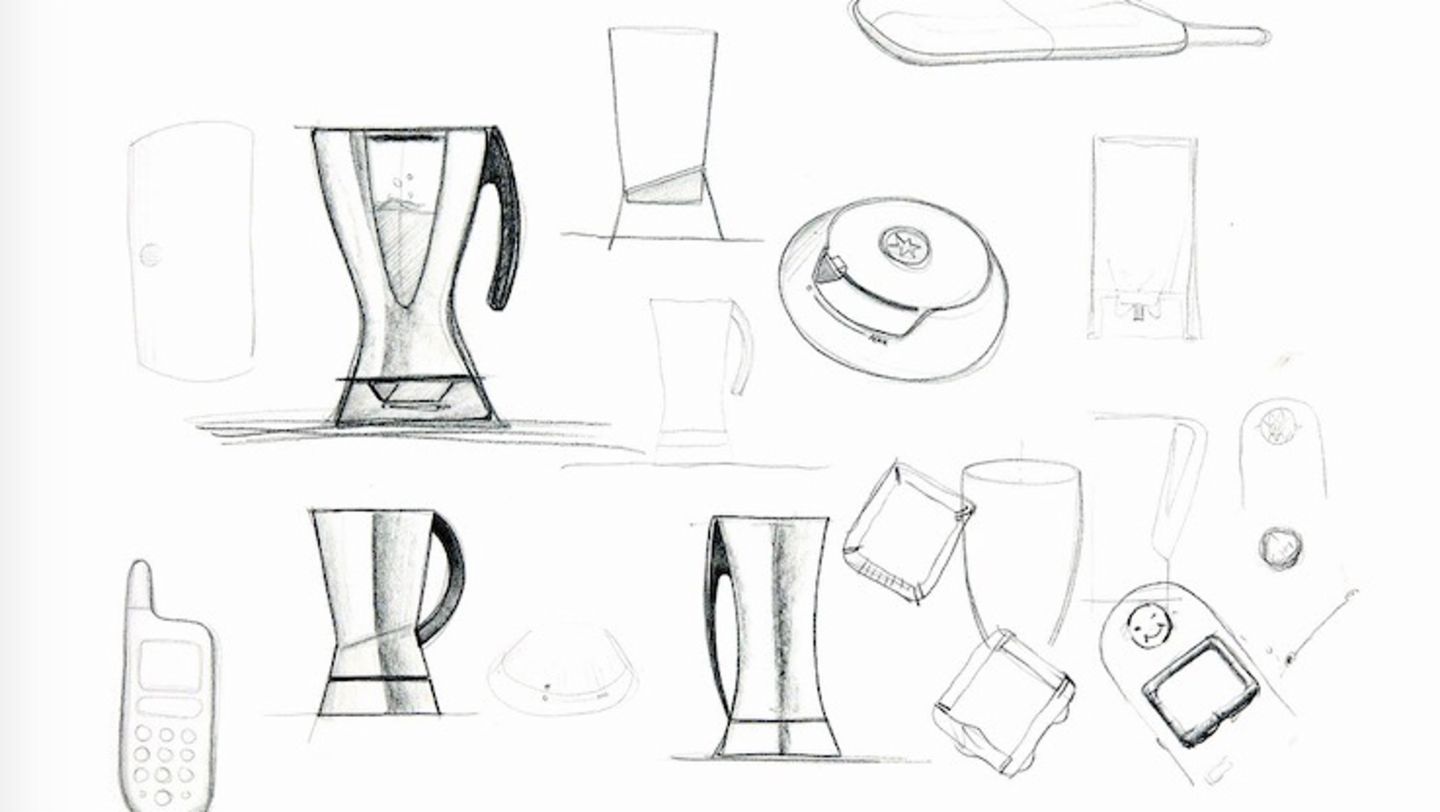

It was a similar story with the breakfast series for Siemens, which is one of Christian Schwamkrug’s favorite products to this day, partly because of the unusual way it was born. “Until the mid1990s, small kitchen appliances were usually made of plastic or very simple material. When we were asked by Siemens to design these appliances, we focused on a high quality look and feel and material selection,” says Schwamkrug. Studio F. A. Porsche designed a toaster, a kettle, and a coffee machine with a clear, straight forward beauty underscored by an aluminum profile. Object and appliance in one. “I was convinced by our designs and didn’t think anything could go wrong,” recalls Schwamkrug.

In the first customer survey, however, the studio only came second behind a competitor that Siemens had also tasked with develop ing a concept for small appliances. “I was shocked,” says Schwamkrug. But then something unusual happened: the head of small appliances at Siemens followed his gut instinct rather than going with the customers’ first impressions, and awarded the contract to Studio F. A. Porsche. “That was very courageous of him. It could have ended badly.” That courage would pay off. Due to the high sales price – aluminum is not cheap and the production costs were relatively steep – Siemens calculated that, for the kettle, it would need to sell at least 100,000 units to break even. It actually sold more than ten times that figure – an incredible 1.2 million.

“The series had its own very special appeal. Suddenly, people were proud to own such a coffee machine or kettle. The products were of ten seen in kitchens in German detective TV series such as ‘Tatort’ and ‘Derrick.’ No one could have predicted such success,” says Schwamkrug. But this is no coincidence. You obviously cannot plan success, but you can make it more probable. Porsche Design proves this time and again because the company’s designers carefully examine every detail until no questions are left unanswered, and because they never forget how important material, functionality, and puristic form are. It is always a small marvel when an idea, a collection of thoughts, leads to a product that you can touch and use, and that simplifies and enriches your everyday life. Many hurdles need to be overcome in order to make this marvel a reality. For fifty years now, Porsche Design has known exactly how to achieve this goal.