The Porsche double-clutch transmission, or PDK for short, first used in racing in 1984 in the 956 for testing at Imola, proved a massive relief for the drivers. Stuck was one of the most eager test drivers: “It was a fantastic experience for me to get to know the PDK,” says ‘Striezel’ today. “It proved to be an advantage from the first lap in Weissach, although the lap times were initially a little slower due to the extra weight. You no longer had to let off the gas when upshifting, but could simply keep it floored. And you couldn’t mis-shift any more. At first we had to shift gears with a normal gear stick, which was pushed forward or pulled backward. Soon there were two buttons on the steering wheel – top for upshifting, bottom for downshifting. This meant you could even keep your hands on the wheel in corners. But steering without power steering remained exhausting. At some point there was the idea of installing a steering aid. Bott just said that we boys should train our arms a bit more instead.”

Derek Bell was sceptical about the new PDK technology at first. He had doubts about the reliability of the dual-clutch transmission in endurance racing and the number of stops to install new driveshafts. “But Porsche taught me a lesson: every race is a step in the development. And it worked, because ultimately those in charge had to answer for the technology to their own bosses on Monday morning. The more we used it, the better it got.” For his part, Stuck had no qualms – which had something to do with his time testing the transmission. “I would often drive three or four stints with PDK in Weissach, and then the tank was empty. It would then be filled up and the security people were still there, but the mechanics clocked out. I would empty the tank again, put the car in the garage, close the door and drive home. It was fantastic.”

Implementation of the PDK

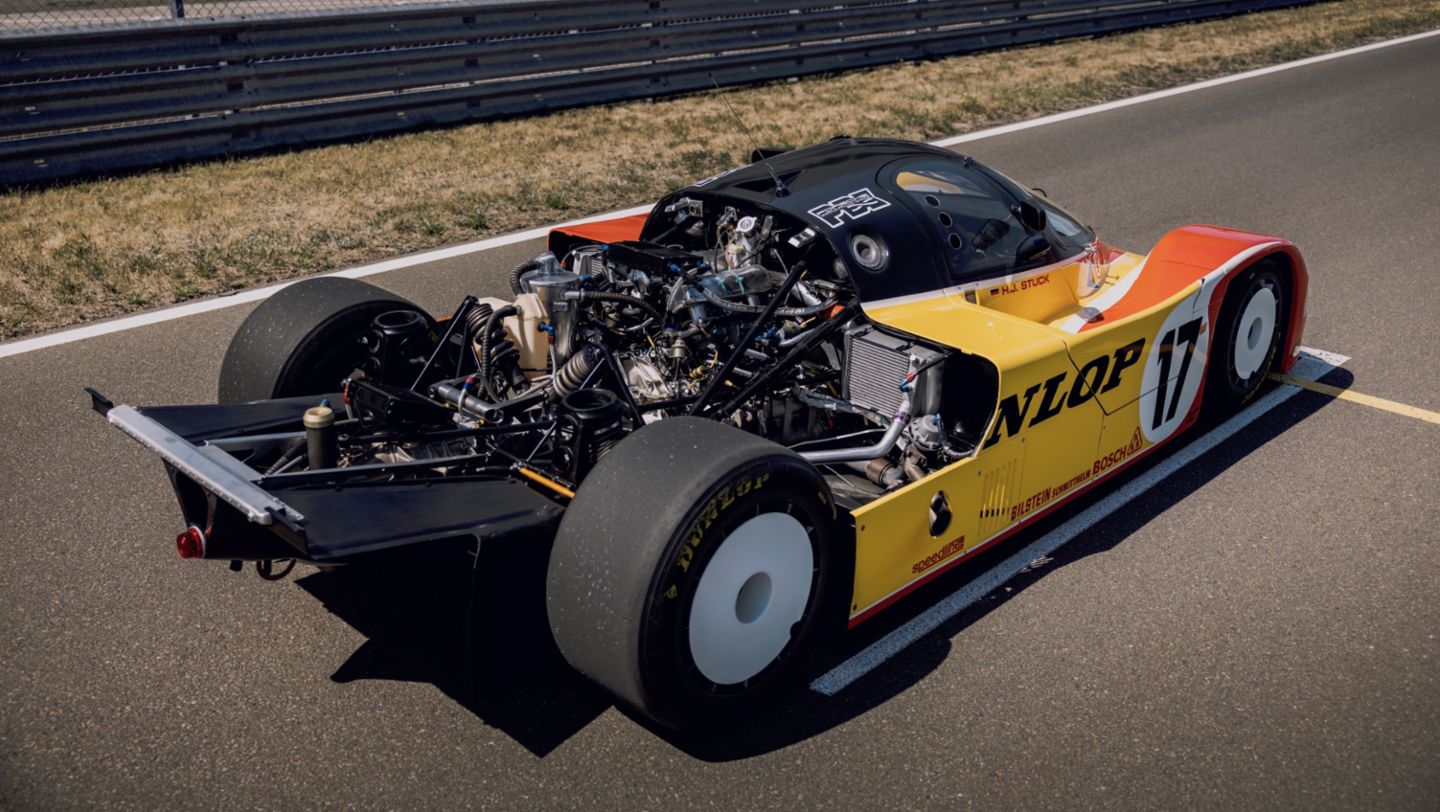

Jochen Mass first had to get used to the new technology. “The PDK, after all, meant 15 kilograms of extra weight. That 15 kg makes a huge difference when it comes to handling. Because wherever you put it, the car slows down a bit.” The finished PDK, which now no longer required too much power from the engine, with which lap times in testing were now faster than without it and which finally demonstrated its reliability, was installed in the Porsche Group C racing cars in 1986/1987.

An IMSA rule change in 1984 turned the 956 into a 962. Mass explains: “The 962 now simply had more space for the driver’s legs, which ensured that the driver's limbs were somewhat better protected in case of an accident.” Norbert Singer continues: “In the 962, we moved the front axle 12 cm forward. The layout was the same, only the front overhang was shorter. But it was a bit of work to get the same downforce at the front.”

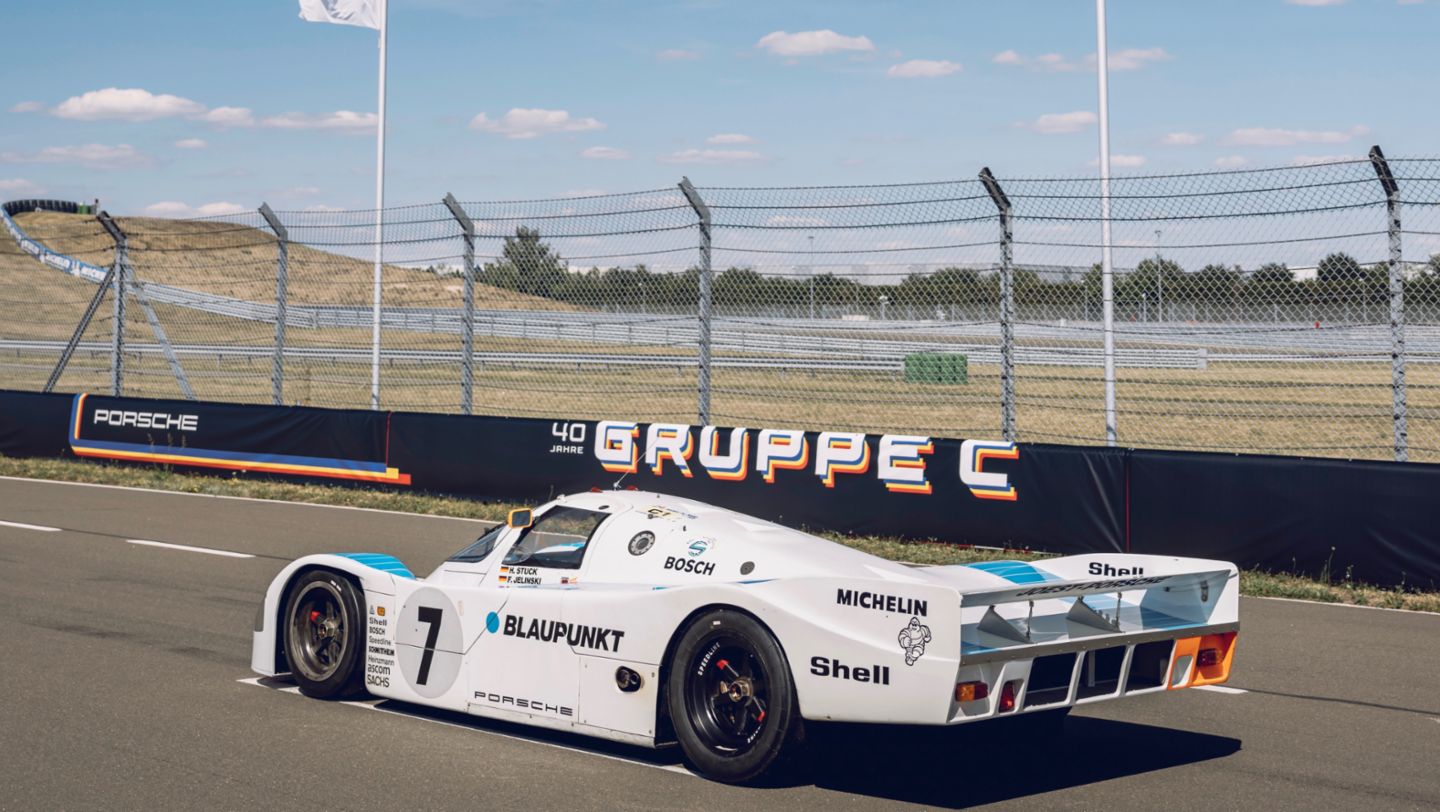

The lifespan of the 956/962 was so long that subsequent DTM star Bernd Schneider actually drove a 962 in the early 1990s. “The car was an immediate fit with my driving style,” says Schneider today. “But fortunately we had electronic systems for saving fuel by that time. I didn’t have to tape a note to the steering wheel. Sometimes we had up to 900 PS at our disposal. For me, the ground effect in particular was great. I came from Formula One, but at the time the engines weren't particularly powerful, so there wasn’t much downforce there. When I got into the Porsche, it was incredible. In the fast corners in Spa like the Eau Rouge, we drove full throttle in 1990 with qualifying tyres and in qualifying mode.”

At the end of its triumphant run, the 962 ultimately became a curiosity as the prototype mutated into a GT racer. From 1993, GT cars displaced the sports cars of group C – including at Le Mans. Singer: “Back then Jochen Dauer paid Porsche a visit. He owned several 962 racing cars, but he was no longer able to use them. He asked for help getting a road licence for the 962. At first Porsche declined, but when McLaren offered the F1 with Formula One technology, three seats, a luggage compartment and road approval, they took a 962 and converted it into a road car with a body from Dauer. He was able to compete at Le Mans for just one year, 1994 – and we won the race.”

Before the racing drivers got back in one last time, Timo Bernhard summed things up: “I saw nothing but smiling faces. And the fact that Porsche can still present these racing cars in such form is thanks to the team’s expertise and passion for motorsport history.” And with that, the WEC champ set off on his final laps in the 956/962 together with the former racing drivers on the company’s own circuit in Leipzig. When they got out for the last time, Bernhard, who followed in the 962 IMSA from 1984 Schneider in the 962-006 from 1987, could hardly contain his exhilaration: “Bernd, there were actual flames coming out of the tailpipe.” Both the Group C racing cars and the drivers of yesteryear are still – metaphorically at least – on fire.