Hidden Treasures

Archaeological exhibits and architectural finesse – the parking garage by Zurich’s opera house is a modern museum – but also tells a story that is more than 5,000 years old. We join the car park attendant on the night shift in his underground workplace.

On this Friday evening in early spring in Zurich, the audience has the choice between tragedy and comedy. The tragic is on offer up above in the opera house – Dialogues of the Carmelites by Francis Poulenc, a tragedy in three acts set in the times of the French Revolution. In the course of the evening, 16 nuns will meet their fate under the guillotine on the stage.

Or perhaps the audience would prefer an opera buffa – a one-man comedy featuring impresario Rico is being presented down below in the parking garage. Rico Würfel is a car park attendant. And his subterranean workplace has a fascinating story to tell.

Clocking on:

Rico Würfel arrives at work in his 911 Turbo S Cabriolet (above). When not doing his rounds in his underground stomping ground, he can be found in the control room (below).When Würfel drives into the parking garage in his white 911 Turbo S Cabriolet, the sports car fits in seamlessly with the vehicles he is entrusted with by the operagoers. The car park attendant comes across as someone you wouldn’t have to ask twice for an interesting conversation. Würfel is a gifted communicator who is at his best not only when talking about his 911. It is as if this were Rico Würfel’s subterranean stage. The setting is certainly apt as the Opéra parking garage is anything but ordinary. This is why we are here. We want to know about the 5,000-year-old secrets that once lay buried here.

Opera house:

The Sechseläutenplatz square above ground was renovated when the parking garage was built. A view of the opera house, which opened in 1891.It took 13 years for the Swiss city’s classiest parking garage to be planned and built. It now lies underground out of sight, with only the striking entrance piquing people’s curiosity and effusing architectural finesse. What’s unusual here is that the opera house is located at the northern tip of Lake Zurich – with the underground parking garage being built directly in the body of water. The higher of the two parking decks is up to two and a half meters below the water level.

In a city which is world-famous for its bank vaults, the parking garage would appear to be a safe, too, and is under the round-the-clock surveillance of 66 cameras. It serves as a temporary safe haven under Sechseläutenplatz square for 288 vehicles. Sports cars, sedans, and convertibles are trustingly placed in the car park attendant’s hands. You could, of course, simply shrug your shoulders like Bettina Auge, the opera house’s press spokesperson: “The parking garage? You park your car and don’t hang around in the exhaust fumes.” But Würfel keeps a clear head here, too. The 52-year-old has been working down here for six years. And it doesn’t take long for us to see that he makes this delightful, bright, functional building a more friendly place.

There’s no time to linger – he has to perform an inspection round with his coworker from the early shift. Würfel is unruffled. The job does obviously have its downsides – cleaning the upper deck, removing tickets that are stuck in the ticket machines. But it is a job that offers a lot of freedom and all kinds of incalculables. “I don’t know what boredom is,” the car park attendant says. “You never know what’s round the corner, and that’s what makes it so interesting.” And yet he does know to a degree what’s coming – he is familiar with the crowd and the localities, the opera house, the Bernhard Theater, the Mascotte music club.

Atmospheric:

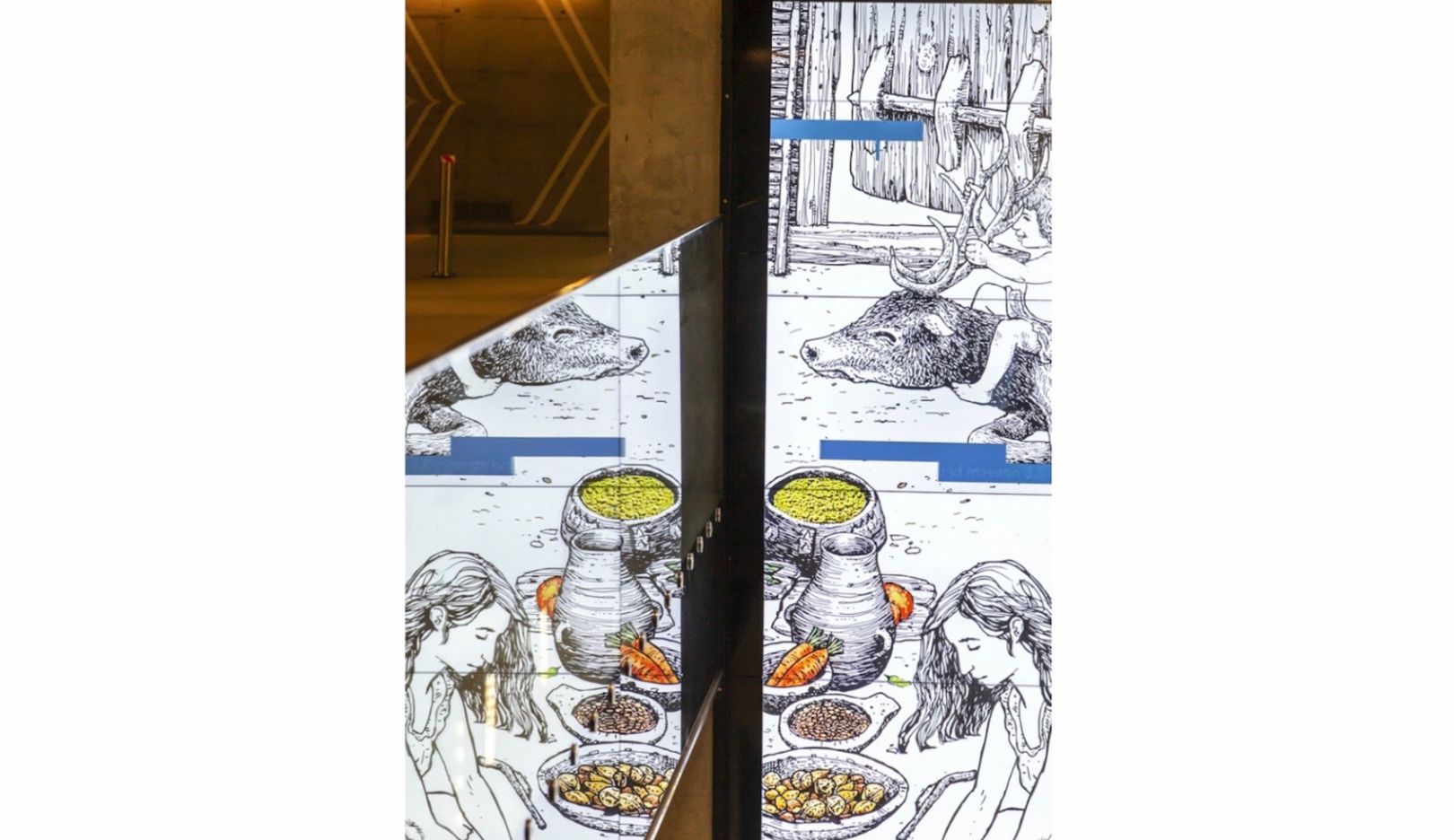

Video projections of the current opera program flicker across the walls and whet the visitors’ appetites for the evening’s entertainment.The evening proceeds. The gong will sound shortly and the nuns will march out in the opera house. In the parking garage, the latecomers are in a hurry. Würfel makes his way around his stomping ground. The qualified roofer has now been living in Switzerland for 20 years. He grew up in Frankfurt an der Oder in the former East Germany, not far from the Polish border. He was 19 when the Berlin Wall fell. But Würfel stayed and dreamt of a Porsche and a fulfilled future. “I then emigrated when I was 32,” he says. “I simply traveled down with my coworker Michael and looked for work. But I found a lot more.” Würfel met his wife, adopted her son, and eventually found his job at the parking garage. “I love to talk and am very communicative,” he says with a satisfied smile on his face. “It’s just what I need for the job. And you obviously need a degree of happiness, too.” His job is crisis-proof and weatherproof. Würfel the roofer now works below ground. When he starts work in the morning, he is curious to see what the weather will be like above ground at lunchtime.

Würfel is also a museum custodian. He leads us to the other end of the garage where you exit to the lake and announces: “Here’s the Archaeological Museum that’s part of the parking garage.” We now hear the full story of this extraordinary place. When the excavators rolled in to dig the excavation pit for the parking garage, numerous artifacts of international significance were found. What the archaeologists found there dated back to the Bronze Age, in other words approximately 5,000 years ago. The building work was immediately suspended for nine months and a team of up to 60 archaeologists worked around the clock to preserve the traces found there. The investigators soon determined that people had been living here where vehicles now find a temporary home in around 3234 BCE. The vestiges of the settlements optimally preserved in the wet lake bed are part of a whole array of lake dwelling settlements in and around Zurich. Beneath this sensational find, there lay the world’s second-oldest surviving wooden door, some 20,000 animal bones, and prehistoric tools such as ladles, bows, and flint axes. The ancient settlements in the region now have UNESCO World Heritage status.

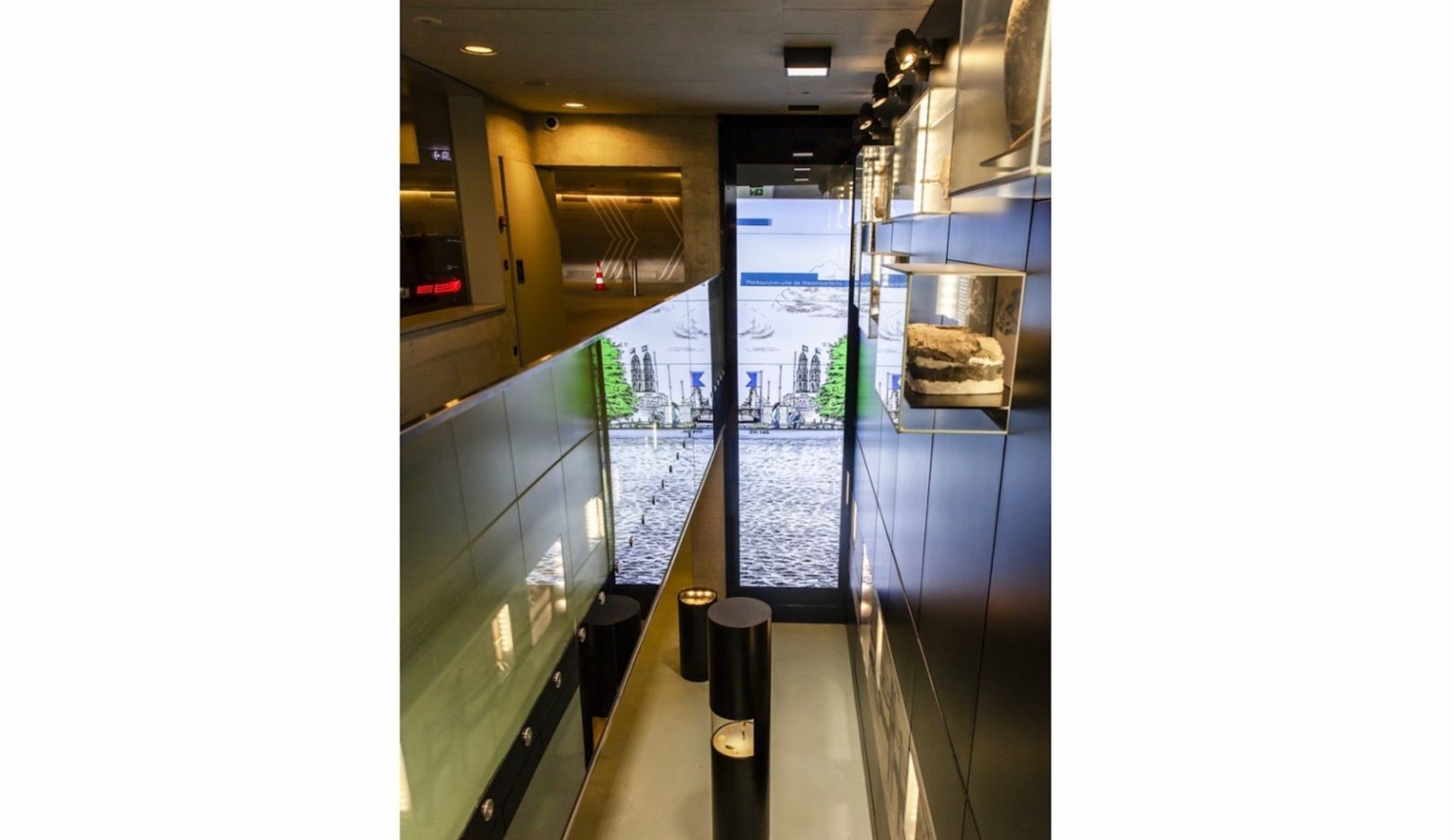

Archaeological window:

The parking garage invites people to linger. The museum section has artifacts from the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age on display.The parking garage is now a place of discovery, a place where modern architecture and archaeology meet. A sculpture by the Swiss artist Gottfried Honegger above the access ramp welcomes the operagoers and there are midnight-blue noise barriers that are reminiscent of a curtain. There is music playing and video installations flicker theatrically across the walls. Over there on the lake side, the Archaeological Window can be visited. Relics from 5,000 years of history are on display in glass cases. They are now neatly lined up here after what seems like an eternity in the waterlogged ground – a fishing net, a cape, hats, flint axe blades, and artifacts made from wood, bone, and antlers. These are the belongings of people who once lived here in a settlement made up of rows of pile dwellings on the lake. Cars now park below it – with thousands of years of history separating the two. It is surreal how history sometimes encroaches on the present.

Daily life in a parking garage:

Operagoers head back to their car (above). Würfel in front of his 911 – his sixth Porsche (below).The underground design serves as a festive prelude to the opera.

Here at the Opéra parking garage, history is vividly presented. Würfel now takes us on his evening inspection round. He unlocks metal doors behind which technology hums and wastewater rushes through pipes. In the control room, he checks the surveillance images on the screen. It’s a quiet night. Würfel looks out of the window at a sea of cars. He, too, has a collection, he says. “A contemporary one!”, he says as he looks at his own white 911. “Six Porsche, one after the other,” he laughs. Würfel is aware of the fact that Porsche-driving car park attendants are something of a rarity. “For a long time, the idea of owning a sports car was merely a childhood dream. But I am enterprising and I pursue my dreams.”

Up above on stage, the tragedy is just coming to its dramatic end. It is followed by rapturous applause and a standing ovation. Down below, the first cars will soon be audible as the operagoers head back home. Rico Würfel’s shift has come to an end, too. He is met with applause in the form of the roaring of high-cylinder engines. “I found happiness here,” he says as we part ways. Here in Switzerland, beneath the opera house. And then the rear lights of his 911 disappear into the Zurich night.