Porsche and Star Wars

Doug Chiang, vice president and executive creative director of the Star Wars universe, gathers inspiration while driving his Porsche.

Even when thick fog envelops the Golden Gate Bridge, the drive to San Francisco is a creative delight for Doug Chiang. At the crack of dawn, the designer climbs into his silver Porsche Boxster S (built in 2005) and drives to his studio at Lucasfilm. “When the weather permits, I open the roof to feel the wind in my face,” says the fifty-eight-year-old. “The sound of the car and the sense of contact with the road give me a jolt of exhilaration every time. I feel the power and the elegance. That feeling flows into my work, into the design of a new spaceship, for example.”

Final stage:

The development of new characters, flying objects, or entire galaxies goes through three stages. The starting point is the idea, followed by sketches on paper. Stage three, the final artwork, is done by the head designer on a huge tablet.Chiang is in his office—really more of a studio—by six thirty on the dot. It’s the place where he’ll spend the next twelve hours. Together with his small team, he invents mythical creatures, robots, and entire galaxies of planets for the Star Wars saga. Sets, characters, and spacecraft that have thrilled millions around the world for decades. As the head of the art department at the Disney subsidiary Lucasfilm, Chiang is responsible for all elements of the sprawling Star Wars universe. From films and TV series to computer games, and even the new theme parks.

Notwithstanding the rapid expansion of the fantasy world conceived by George Lucas with the big bang of the first film in 1977, Chiang has always held fast to first principles as a designer: “Good design doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The starting point is always research in the real world. Even the smallest detail can be interesting,” he explains in his office, a space dominated by two large desks. On one of them, Chiang sketches his ideas with felt-tip pens and gray markers before scanning them and, on another desk, refining them on an oversized tablet connected to three monitors.

“I constantly collect details and images that I encounter—streetlamps, landscapes, microscopic organisms, the interplay of light and shadows. I can draw on these later.” At one point his collection of inspirational artifacts included hinges from European cabinet doors, which Chiang had discovered by chance in a catalog. He was fascinated by the mechanics and procured an entire collection. A few years later, the hinges served as a model for suspension systems on his spacecraft.

“Good design doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The starting point is always research in the real world.” Doug Chiang

Model worlds:

In his studio at Lucasfilm, the fifty-eight-year-old designer collects inspiring accessories from the worlds of androids and automobiles.Chiang describes his design philosophy as follows: “I start with a silhouette, a sort of logo that’s instantly recognizable. In the movie business, the three-second rule applies: viewers must be able to grasp the situation quickly. There’s no time for explanations. Every design has to have a personality. Even a new world or space ship has to signal instinctively whether it’s in league with the good guys or the bad guys.”

Trusty companions:

A clone trooper of the 501st Stormtrooper Legion, droid K-2S0, and an imperial drone—characters from the "Star Wars" saga populate the desk of Doug Chiang.Chiang owes this straightforward mental framework to his mentor and former boss George Lucas. In the early 1990s, Lucas gave Chiang a job in design—shortly before filming the second trilogy in what would become a total of nine Star Wars films. The job was the fulfillment of Chiang’s greatest wish: the Taiwan-born designer had dreamed of this opportunity since he was a young boy. “Creating robots and mythical creatures has always been my great passion.” As a child in Taiwan, he scratched out his ideas in the dirt using a stick. Later, as a teenager in Michigan, he would shut himself in his room and create fantasy worlds on paper.

Then came his great awakening: at the age of fifteen, Chiang saw the first Star Wars film in the theater; a year later he saw a documentary about the work of the filmmakers collaborating with George Lucas. “Those experiences changed my life. For the first time I realized that what I was doing at home could be a career,” recalls Chiang with a smile. “Somehow I had to find my way to George Lucas.” The young enthusiast raided the local library for books about filmmaking and went on to make his own stop-motion films—animated films in which his sequentially shifted lineup of figures gradually learned to walk, step by step.

When he was twenty, Chiang moved to Los Angeles and enrolled in the film school at UCLA. He gained his first experiences in the field directing TV commercials, before the fulfillment of his lifelong dream suddenly appeared within reach in 1989: Lucas’s special effects company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) was looking for freelancers for a short project. Chiang went all-out, packing his belongings and riding his Kawasaki 600 motorcycle north to San Francisco.

He got the job, but he was in for another shock as well: “For starters, it was intimidating to see what a high level they were working on and how much I still had to learn. The second thing was that I learned that Lucas didn’t want to make any more Star Wars films. My dream seemed to be at an end on my very first day.”

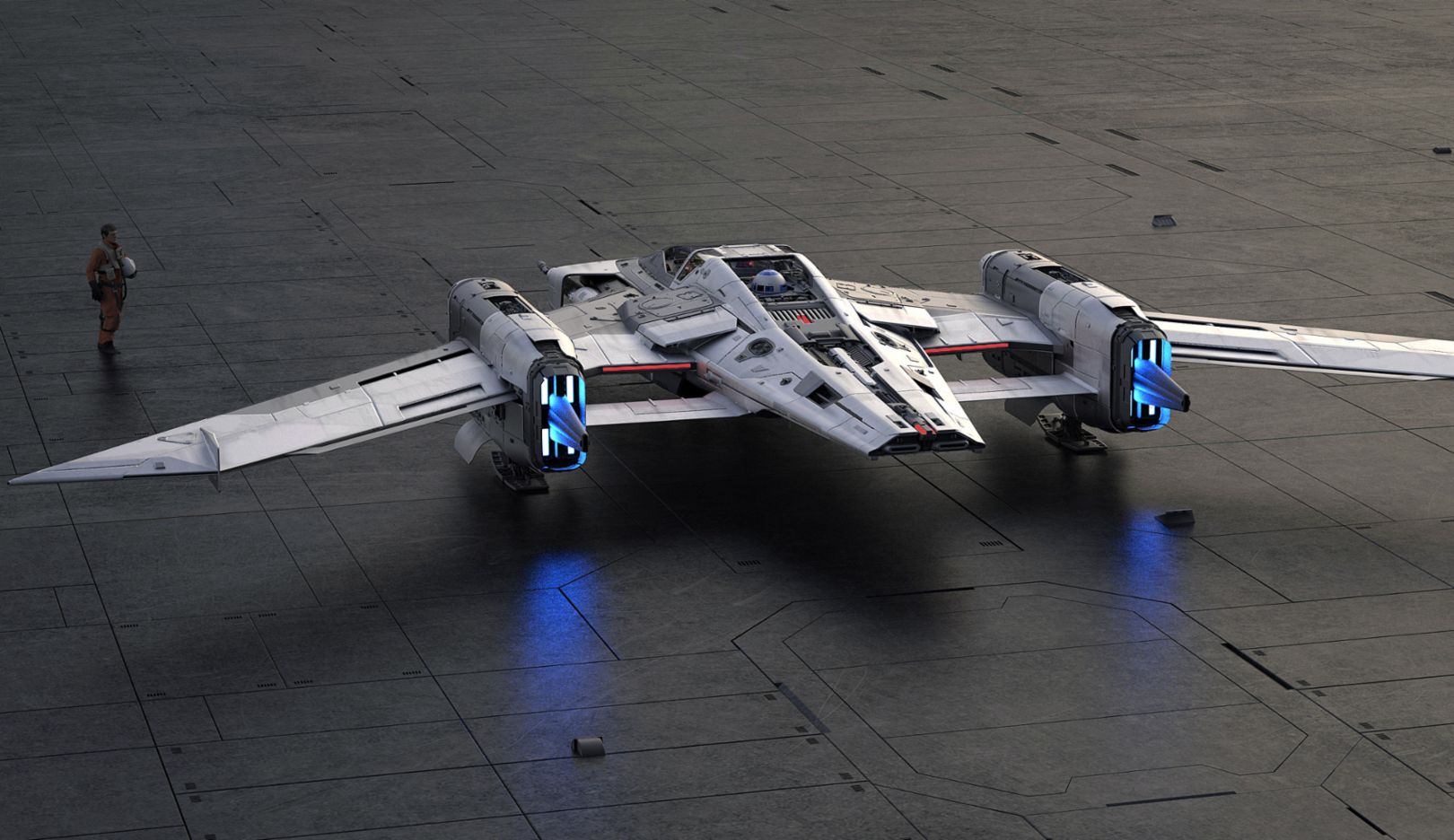

Symbiosis:

The Tri-Wing S-91x Pegasus Starfighter is the outcome of the designer alliance between Porsche and Lucasfilm.As a young ILM employee, Chiang resolved to spend every evening and weekend for a year just working on his craft, to become a better designer. He designed costumes, creatures, and vehicles by hand and on the computer. He taught himself the techniques of painting and picture synthesis. By the time he was named ILM’s creative director for visual effects, in 1993, he possessed an extensive, albeit entirely private portfolio of fantastic space-related ideas—as well as an Oscar for the visual effects in the film Death Becomes Her.

As if rewarding him for his dedication and painstaking work, George Lucas announced in 1994 that there would be more Star Wars films to come after all. Chiang threw all his courage and creativity into the ring and submitted his portfolio—anonymously. Lucas was instantly impressed by the wealth of ideas, and the two came together in a meeting of minds. In 1995 the creator of the saga named Chiang the art director for the entire Lucasfilm enterprise. Chiang was now the art director of Star Wars. Light years away from that small boy who had drawn spaceships in the dirt with a stick, yet still driven by the same exuberant spirit.

Lucas and Chiang got down to work, defining the chronology and visual language of three further Star Wars episodes. They would tell the background story of Darth Vader, as well as that of Luke Skywalker’s companions. A look back at the future. The films were released as Episodes I–III between 1999 and 2005.

Reaching for the stars: Doug Chiang put it all on the line to find his place in the Star Wars cosmos. His job as head designer is a dream come true.

Today Lucas, now a man of seventy-five, lives not far from Chiang in Marin County, north of San Francisco. “Although George has since stepped back from an active role in the business, he’s still the best mentor anyone could wish for,” says the designer. “Whenever I have questions, he’s always ready to help out. It’s his universe, after all. And no one knows it better.” That’s no less true for the new Star Wars TV series The Mandalorian, the second season of which was filmed in early 2020. Chiang is also advising the film legend in the creation of his Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles.

With so many responsibilities in so many galaxies, the father of three—his eldest has graduated from college, while the youngest is still in high school—doesn’t have much downtime. “It’s exhausting to lead a global design studio that’s working around the clock,” concedes Chiang. “I try to recharge my batteries on weekends. I do a lot of yoga and go for walks along the ocean or bike in the mountains. Appreciating the importance of nature, if you want to stay creative—that’s another thing I learned from George Lucas while working with him at his Skywalker Ranch.”

Place of inspiration:

Designer Doug Chiang enjoys his daily morning drive to work in his silver Porsche Boxster S.Chiang also fulfilled another of his childhood dreams: bringing the worlds of sports cars and spaceships closer together. “Even as a young boy, I dreamed of driving a Porsche. After Episode I was done being filmed, I rewarded myself with my first Boxster.” It’s no wonder that he was immediately taken with the idea of designing a Porsche spaceship in collaboration with the team around Porsche’s chief designer Michael Mauer. After a fifty-day sprint, with three meetings in Weissach and San Francisco as well as numerous video conferences, the Tri-Wing S-91X Pegasus Starfighter was unveiled in late December 2019—perfectly timed to coincide with the premiere of the current Star Wars episode, The Rise of Skywalker.

“The spaceship has the DNA of Porsche and “Star Wars” and could exist in both worlds.” Doug Chiang

“Our design philosophies are very similar,” says Doug Chiang of the collaboration between Porsche and Lucasfilm, “although we work in different worlds.” He laughs. “For films, I don’t have to worry about how big the engine or gas tank is. We don’t have to comply with any safety regulations, and our spaceships don’t have to function reliably, day in and day out,” says Chiang, describing the context of his work. “But just like Porsche, at Star Wars we still labor under the same rules in terms of design.” It’s all about proportions. “Silhouette, aesthetics, and details have to make the essence of the brand recognizable at a glance.” In this case, the rearward-tapering cabin of the S-91X, the topography of the cockpit, and even the turbines draw noticeably on the design of the Porsche 911 and the Porsche Taycan.

“This spaceship has the DNA of Porsche and Star Wars and could exist in both worlds—if certain technologies existed, that is,” says a grinning Chiang of the star Porsche. The spaceship will be deployed in one of the upcoming Star Wars productions, affirms the creative director. “Our collaboration has resulted in the creation of a strong design. We just have to determine which of the future stories will be the best fit for it.” No doubt Doug Chiang will be cultivating ideas on the subject tomorrow on his daily drive over the Golden Gate Bridge as he makes his way to Lucasfilm, heading toward the future.

SideKICK: Museum of Narrative Art

George Lucas made Doug Chiang the art director of Lucasfilm in 1995. Their collaboration started with Star Wars Episodes I–III, which were released between 1999 and 2005. Lucas has since stepped back from an active role in the film business. Their current joint project is called the Museum of Narrative Art.