A pencil draws fine lines across a sheet of white paper; the soft scratching of the graphite the only sound to be heard. Chh, chh, chh. The man holding the pencil is sitting at the breakfast table in a hotel in St. Moritz, high up in Switzerland’s Engadine Alps. Wearing a focused expression, he appears thoroughly engrossed: a designer in his element.

Almost at the same time, just a few kilometres away, the morning sun is casting long shadows over a still-frozen ski slope. The approaching sound is not unlike that of the pencil, although in this case the lines are a little longer: chhhh, chhhh. A man in a purple racing suit sweeps down the slopes before disappearing as a small dot over the next hilltop. This time it’s a downhill skier in his element.

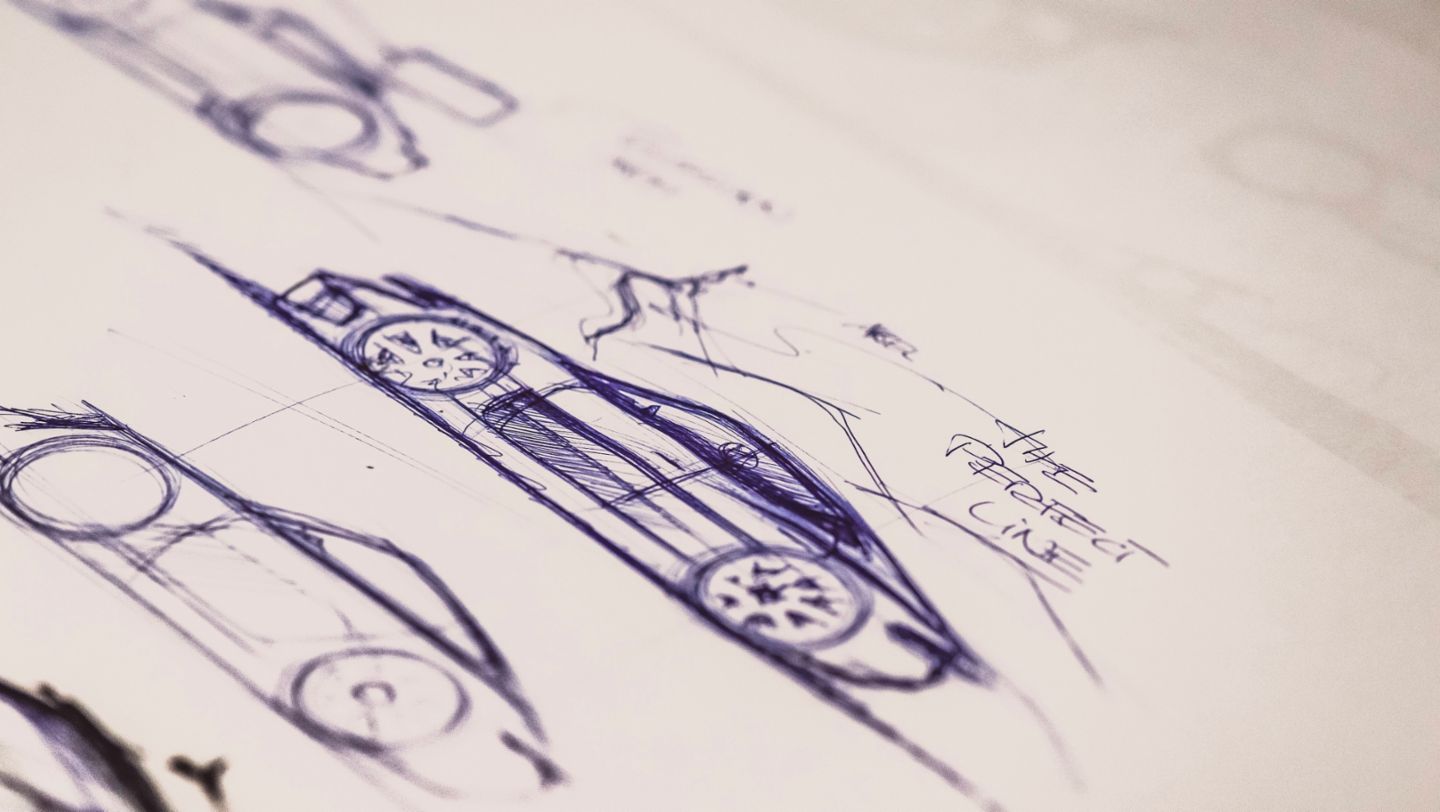

The lookout for the perfect line

The two men have something in common: both are constantly on the lookout for the perfect line. Skier Aksel Lund Svindal has achieved just about everything anyone could accomplish in alpine skiing: two Olympic gold medals and five world championship titles. Away from the slopes, he has been passionate about sports cars since he was a child.

Michael Mauer has achieved similar success in the automotive sector. Together with his team, he is responsible for the design of one of the world’s leading automobile brands. With the Taycan, Porsche has recently provided a glimpse of the electric mobility of the future. Mauer has been an avid skier since childhood and even worked as an instructor before studying automotive design.

Creativity thanks to alpine sports

“I believe you have to give your brain some time out on a regular basis and give yourself the chance to think about something completely different,” says Michael Mauer, as thick flakes of snow begin performing pirouettes outside. “In my case, it boosts my creativity. After a day in the mountains, I feel more inspired in my day-to-day life. It frees the mind.”

For Mauer, alpine sports have more to do with creativity than many might think. “Skiing requires qualities in people that are beneficial everywhere.” Svindal, who has joined his friend, wants to know what these are. Mauer replies: “When you’re standing at the summit, there’s no finished picture. Everyone has to find their own line.”

This approach is fundamental for designers in particular: “Form is the ultimate expression of a brand in a product,” says Mauer, as he describes the dramatic height-to-width ratio of a Porsche and talks about its full-bodied stance. “Ultimately, the curved surfaces have to create something like high tension in the viewer.”

Svindal compares this concentration on a single line to the races he has taken part in during his career: “You only have about 90 seconds of racing time on average – and as a downhill racer you don’t have a racing car to protect you at 140 km/h. So you have to know every inch of the track in your head.” In addition to your own actions, he explains, there are all kinds of variables: “Wind, weather, the surface, visibility conditions – these factors are always different.”

The perfect race as the perfect line

According to Svindal, the aim is to achieve the perfect race in the given conditions. “This is a kind of perfect line, too – in fact it’s a never-ending optimisation process.” This is where the Norwegian draws his motivation: “A good racer gains satisfaction from getting close to the ideal – which of course no one ever quite achieves. Even if you win, you know you’ve made mistakes.”

While a designer’s incentive is to come up with completely new concepts, Aksel Lund Svindal has become a successful entrepreneur: he is a partner in several start-ups and runs a successful luxury hotel in Norway. Has he ever experienced defeat? Only those who are never completely satisfied are successful, says Svindal. “Something can always go wrong. If you never really try, you’ll never end up competing for victory. If you’ve given it your all and you lose, the defeat hurts but you see where you really stand.”

In sport, as in everyday life, the thing you need above all is passion. This is something these two professionals – both skier and designer – firmly believe in. Svindal: “As a former professional, I have had the privilege of meeting all kinds of people from different sectors of the economy. They inspired me to start my second career because they themselves were in business with the same passion.”

Taycan to become icon that sends out a powerful signal

Mauer agrees with him: “You should never stop wanting to learn and develop.” This helps you focus on the future, he adds. “Our aim with the Taycan was to achieve what the Porsche 911 did in 1963: we wanted to create an icon that sends out a powerful signal. Ideally not just for Porsche, but universally. We won’t have achieved it until the Taycan has become synonymous with sporty electric driving.”

Outside the hotel, against a backdrop of the Piz Rosatsch and Piz Surlej mountains to the right, and the Piz Vadret and Piz Muragl to the left, the two men get into a white Porsche Taycan, their skis loaded in the luggage compartment. Almost silently, the electric sports saloon glides along serpentine roads towards its destination – a car park near a ski run. It’s time for the two friends to swap notes on the slopes.